Celebrating 50 Years of Excellence

A Tribute to William B. Gould IV

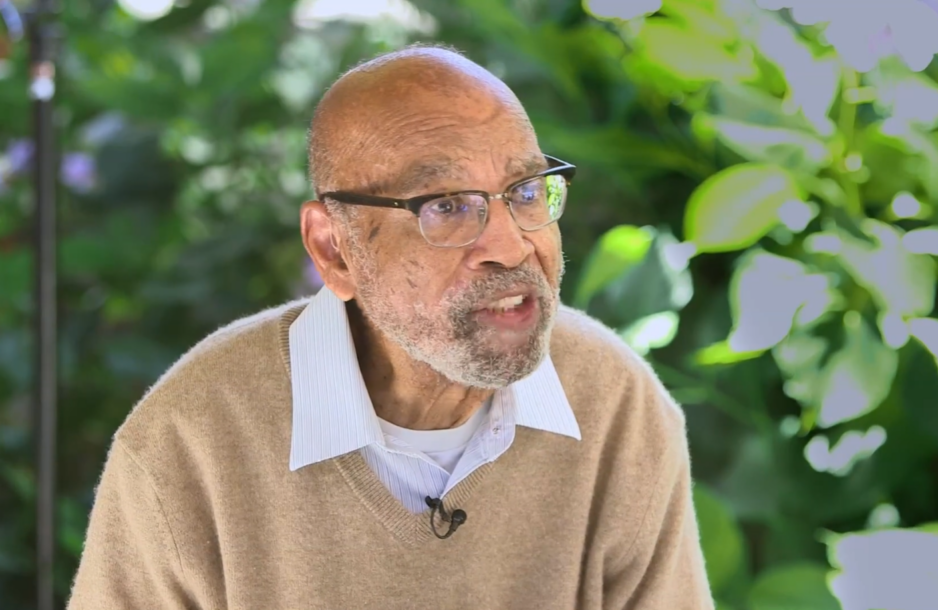

William B. Gould IV, Charles A. Beardsley Professor of Law, reached an incredible milestone of 50 years of dedicated service in 2023. His passion for law, commitment to justice, and unwavering dedication continue to make an indelible mark on the fields of labor law and labor relations. Join us in honoring his remarkable achievements and contributions. Let’s take a journey through the milestones of his illustrious career.

Special thanks to Alan B. Pick, JD ’70 and the Hon. Richard L. Morningstar, JD ’70 for their time, energy, and commitment as alumni volunteer leaders in creating this special celebration of the impact and legacy of Professor William B. Gould IV at SLS.

SHARE YOUR MEMORY, ANECDOTE, OR REFLECTION IN HONOR OF PROFESSOR GOULD HERE.

On Thursday, October 19, 2023 past students, alumni, colleagues, friends, and family came together to celebrate Professor William “Bill” B. Gould IV and the impact he has had on the SLS community since joining the SLS faculty as the first African American professor over 50 years ago. The video recording of the program featured above includes remarks from past students, friends, colleagues, a fireside chat and closing remarks from Bill himself!

The collection of videos below highlight the many dimensions of the legacy, friendships, and impact Professor William “B.” Gould IV made on generations of students, colleagues, and friends.

Because he very much enjoys that kind of human interaction. I will wear this, but only for you, though. He’s the only person I know who takes the score has a scorecard and and actually records every out of every pitch. Yeah. His knowledge of baseball, Red Sox history and lore is encyclopedic.

It just he has every relevant statistic about them, and and I thought I was a big Ted Williams fan, and I thought I knew it put me to shame. I’m getting emails from him very early in the day and very late in the evening. And this has always been true since I met him in 1991. I don’t know when he finds time to sleep, but he’s always got stuff going on. So for me, he’s just like the Energizer bunny.

If you walk into his office, it’s a little bit messy, I think. And you’ll ask him about something he’ll go. Over there, in in that pile over there, about halfway down, you’ll find a case that and it will exactly be where he points to it. I can always count on enjoying my visit with him because I knew there would be some good jazz on. You know, he’s so smart, but he, you know, he he’s funny too, and he’s just absolutely fun to talk to, to be around, you know, ceaselessly kind.

Pleasant, but but not a dictator type know it all attitude, but you know there’s a whole lot more more in that brain than he’s even tells. Welcoming and generous with his time, which he was then, and he has been multiple times since then as I’ve been working as a labor lawyer. There have been times when I, you know, kind of reached a point where I’m stuck in my research or my analysis, and I’ve thought, why don’t I call the former chairman of the NLRB? Grandfatherly and supportive. Top of line adjectives are generous hopeful, caring, and active.

Engaged because when you talk to him, he’s he’s engaged in so many things in the world. Present, when you talk to him, he is there. You know, he pays attention. He’s even a It’s it is part of what made him who he was in the beginning, but also keeps him young now in his early eighties. Professional side passionate and indefatigable, and on the personal side, warmhearted and loyal.

When Bill Gould gets to work on something, he really pushes to the end and doesn’t, you know, let things go and just drop things. He he’s really just such a persistent person. He he was always very encouraging, and you could tell that he was always interested in helping you get to where you wanted to be. I don’t remember going to him asking for things. For example, I’m going to LA.

Do you know people there? He offered. He acted, but he wasn’t profuse. He wasn’t, he was more silent in terms of the kind of support. And I was only in two of his classes, but he made a a huge impact on me as a student and really as a human being.

Bill always thought of something, and that always conveyed his love of labor law, his concern for students, and his engagement as a scholar and teacher. You know, other than example of lot of example of successful African American lawyers. So I get to law school and lo and behold, there’s Bill. Oh my god. Bill represented what could be for me and, I dare say, others like me in my class who had not seen a lot of examples of success.

I think whirlwind of ideas is a great phrase to describe him in part because, you know, he wasn’t someone who taught labor law as a static subject where all these principles were settled and there was nothing new happening. He, I think, correctly saw labor law as a dynamic field that’s always changing. I think we worked well together because we really shared a love of sports, family, and the truth. And I think those those are things that really encapsulate a lot of what sort of drives Bill and what he’s he’s passionate about. Bill was my mentor.

I mean, I really stayed in touch with him. And he says, well, have you ever thought about teaching? I said, no. And he says, well, let me scout around and see if there are any openings. I went ahead and took the plunge, and then the rest is history.

I fell in love with it. I would not be a teacher today were it not for Bill. He he has a combination of of intellect, combination of of of of law and also of of feelings that he that he trusts and can and knows how to convey you know, his feelings to you, but back it up, you know, and rhetoric and back it up in in in legally. And there are very few people that I know, you know, that have all those qualities. I’ll use an a a baseball analogy.

He’s a triple threat. In baseball, that means you can hit, run, and feel clearly you know, one of the the best best labor law researchers and and teachers in our field. I use the Jackie Robinson scholar. No one questions it. His scholarship is impeccable.

It’s voluminous, an and I’I’m not sure if you’re a doctor, you’re a doctor. Opened the door. Everybody learned from him. The the the rest of the faculty at the school, the students saw what they were capable of doing through Bill, opening that door so wide.

Effectively. So my name is Alan Pick. I am a graduate of Stanford Law School, class of 1970, and I am proud and privileged to be part of this participation in the celebration of professor William Gold the fourth. Bill is is just now is filled with amazing stories. He has, over the last 50 years, mentor and educated literally thousands of students at Stanford Law School.

We know that he is a leading scholar of labor and employment discrimination law and has taught literally midst of writing his twelfth book at this time. He has written an midst of writing his twelfth book at this time. He has written innumerable argue articles and commentaries about labor law and about employment discrimination law. Stanford Law School was founded in 18 93. And up until 19 72, every professor at Stanford Law School had been a white male.

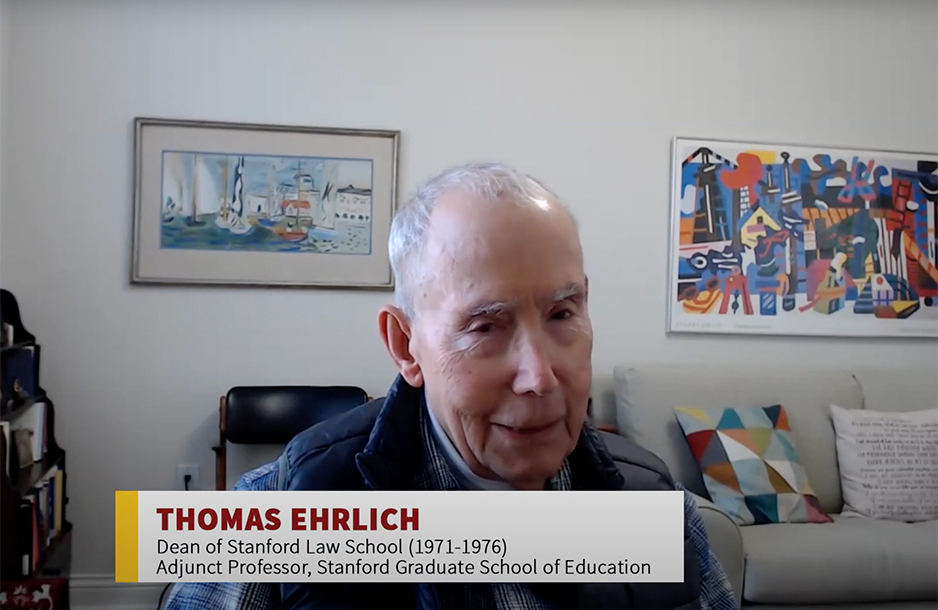

And because of dean Tom Ehrlich and Mike Wald, who are here today, is that they made a decision that it was important to diversify the faculty of Stanford Law School, and that’s when Bill joined the law school and changed the law school forever. In 19 95, when Bill was chairman of the National Labor Relations Board and a baseball strike was an existential threat to the continuation of Major League Baseball. As head of the NLRB, Bill stepped in, found powers in the NLRB that had never been used, and was able to save baseball. And the amazing thing is is that Bill not only did this and all of this in the past stance, but that Bill continues to do it to this day. He’s still teaching classes there.

He’s still reading writing articles. He still appears on television and radio, in the press, in commenting on labor law and employment discrimination law. And so we are all honored to be able to join in this celebration. So I would like to Bill. Thank you, Alan.

When I was first asked to speak about Professor Gould, I thought to myself, WWCS? What would ChattGPT say? But from our time in from our time in Washington, the the State of the Union address, when the House of Representatives is functioning, president goes before the House and Senate, and this house sergeant at arms calls out, mister speaker or madam speaker I have a high privilege and distinct honor to present the president of the United States, who we’ve seen a few pictures of a few of them up there who are associates of Bill. But I feel that way today. It is truly a high privilege and a distinct honor to be before you to share my thoughts and my profound admiration and respect for professor Bill Gould.

As students and and alums, there’s little more that we could do to honor our professors and our school beyond passing the bar the first time, using our legal training in sound and ethical ways, and giving back to our community through pro bono and and other ways pro bono services in other ways. So I’m especially grateful for this opportunity to share a few minutes about how professor Gould stands for what I believe in and have aspired to as a lawyer, public official, educator, and community member. In the fall of my second year at the law school, I took his labor law course. That was in the fall of 19 81. Now if you ask Bill about it, he would automatically quickly say, the Dodgers meet the Yankees in the series 4 to 2, and let me get Dusty on the phone.

He can tell you a little bit more about it. But to me, that’s where I learned about donning and doffing. Obviously, not everybody in here is in labor law, unless they that would be a laugh laugh. I I enjoyed labor law, and I also took another labor law course with him. But where I would say would his his teaching at the law school was way beyond just just in the classroom.

After that course, I went to hear him speak on campus on to talk about the Voting Rights Act. It was it was a program that professor Clay Carson was sponsoring. It was in January of 1982. That predates the national Martin Luther King Day, but it was it but it was in in honor of of his day. And much to my surprise, professor Gould said, he had been reading about me.

Well, during my 1L summer, I I was interning for MALDEF in Washington, DC, and I testified in front of the House Judiciary Committee Voting Rights Act bilingual election provisions. So in preparation for his campus talk, he had read over the hearing transcript and noticed my testimony. So we connected on those issues and just a start of so many other connections on on various things. When I came to Stanford for law school, I was greatly looking for that type of connection to the outside world. The campus was comfortable, was suburban, kinda detached.

So much so that I recall eating in Wilbur Hall, and the students were so upset when president Reagan and John Paul the second were shot, but they weren’t upset about that. They were upset that the TV stations preempted the Gilligan’s Island reruns at at dinner time. So by contrast, in his classes describing labor disputes, talking about the issues of the day, talking about working men and women. Bill Gould, more than any professor I had, provided that reminder to me as to why I was in in law school and the purpose behind all the readings and writings and other academic work. Years later, going through a lot of stuff lot of papers in in my family, I found that previous to my entering law school in 19 79 Bill and I were on in a full page ad as concerned Californians wanting Ted Kennedy to run for for president against against Jimmy Jimmy Carter.

So we had this connection even before I knew it. But Bill offer offers ever present reminders of why we, as lawyers, do what we do, and that should be the hallmark for any professor. I was dean for a few years at the University of San Francisco School of Law, and every quarter, professors would provide me reports on where they had written, what law review article they were in, etcetera. And while that was great, I was more interested in who’s using that scholarship, signing it, what advocates are talking to them about about developing and shaping the law, and what journalists might be turning to them, talking about, about complex supreme court rulings and other legal developments having an impact. And that’s exactly the Bill Gould standard.

It’s done well by other professors to be sure, but no law professor I have had such a long lasting impact on my professional direction Department of Justice, Department of Justice, I served as special counsel for immigration related unfair employment practices. I have the longest title of the department, but in essence, it was leading office, the only office in the federal government devoted solely to immigrant workplace rights. And Bill, of course, chaired the NLRB. Now every administration talks about inter agency cooperation. Well, Bill missed it.

He recognized that immigrant workers on the margins were exploited, were underpaid, and often not paid at all, and that unscrupulous employers could try to play the immigration card against them to keep workers from organizing. Well, Bill cut the red tape, and he got our staffs my staff and his staff to collaborate. So after his time at NLRB ended, our agencies came together along with the EEOC to establish written protocols and cross training so our respective offices, not just in Washington, but at the regional level as well, knew and respected what each other did, referred matters where the other agency could be of more help, and may have had jurisdiction, and collaborate at least not interfere with each other. 1 day, senator Paul Walston, someone else you’ve seen in the pictures today, put us to the test. Housekeepers at the Minneapolis Holiday Inn Express had been taken away and threatened with deportation as they were going into to what they thought was a bargaining bargaining session.

Instead of getting a bargaining session, the employer had called INS on them. Talk about bad faith. NLRB was already involved. Senator Wilson asked us and the EEOC to join in. Because of the the infrastructure that Bill had put in and we had put in, the agencies that work together, the house the housekeepers at the hotel got their union.

They got back pay, and they were protected from from deportation. They got they got temporary relief. That type of collaboration for people would not have been possible without Bill putting it in, promoting it, and inspiring it. For Bill and for me, our work to enforce the laws we administered gave voice to the otherwise voiceless. It might never have occurred to the powerful person or institution discriminating against someone, taking away their job, or depriving them of their rights.

Wouldn’t have occurred to them that there was a government agency that protected that individual and that government agencies was was accessible, would answer the phone, and would follow-up and would investigate and get them their rights. That’s what Bill Gould made possible. Long before Shohei Ohtani, Bill excelled at playing different positions and fulfilling different roles exceedingly well. He’s a professor and a teacher, a public servant. And he’s also been called upon to be a mediator because he has a reputation for being a strong and principled advocate who is fair and trusted by both sides.

We all know lawyers who take controversy and make it about themselves. Bill Gould observes controversy and brings the volume and temperature down a bit, allows all sides to focus in on the problem and the dispute. When that requires taking on the institutions that are supposed to help people and don’t, the people went out in Bill’s view. He calls on courage and truth to remind all of us about our responsibilities for service to clients, to communities, country. Bill was also helpful to me when I went back to Washington DC in the Obama administration assistant secretary for fair housing and equal opportunity.

When I received my briefing on fair lending disparate impact, and other parts of of of the fair housing laws. Very quick mention was there was very quick mention of something called section 3 of the HUD Act. In principle, section 3 says that HUD is spending money. The money goes to companies or contractors that hire people in public housing or hire low income individuals. And It’s not really about housing.

But it’s everything about the people in public housing. And that’s where Bill was so helpful, advising us, advising me in particular on project labor agreements, and ways to make section three work better. It might not have been about the buildings, Once again, making laws work for people, getting lawyers and public officials to focus on the human aspects of laws and policies. Over these many years, 40 for me since the law since graduating 50, since you began teaching at the law school, Bill has opened doors, opened minds, and opened hearts. For countless students and lawyers of all backgrounds, for countless workers, causes, responsibilities, and roles, he has been a guide for justice.

For decades, his beloved Boston Red Sox had Tom Yawkey Way until they changed their name very appropriately. Now here at Stanford and everywhere he goes, the on follow is the Bill Gould way. It doesn’t need to be renamed, but should be followed. So thank you, professor Gold, for always being a pennant winner. Thank you, John.

And now I am Dean Avian Wynn. Good afternoon, everyone. Good afternoon. You’ll have to excuse my voice. I was in Kenya last month and got pneumonia.

And I don’t have pneumonia now, but my voice has not come back. Well, I think what I’m going to say will be in harmony with what Dean Trezvina said. I’m very honored to have been asked to speak to be the voice of many of Bill’s students over the decades. I met him when I was a one in 19 79. I had had a couple of black professors at Princeton where I did my undergrad, and they had And a black professor.

So I sought him out. I was so excited to meet him. And I’ve been asked to speak bringing up the issue of diversity writ large because Bill’s career exemplifies the very best of that. Having a black professor is not just good for black students. It’s good for white students.

If you don’t if a white person never sees a black person as a lawyer or professor or judge, so consciously they may think, oh, well, those people, they don’t do that. And that’s very dangerous for our society. So having Bill as the first black professor and him being that for many years, he was here alone as a black faculty member. He was joined by professor Mendez, his running buddy, who was the first Latino, but he was here for many years. And as we know, of course, today, the very notion of diversity is under attack.

We cannot take for granted the gains that we made back then, that they will continue. Now, even more important. Some of you may have spent your whole career in elite institutions. I have spent the last 37 years as a law professor at the University of Iowa Law School. It has been wonderful.

I am educating students, most of whom are first generation college, much less law school. Our mission is to serve the state, not necessarily the whole nation. And some of my students may not have gone further than Chicago. None of them pretty much none of them attended an elite college. We don’t have the resources of a school like Stanford.

And as we know, what Stanford does gets in the national media. And we are producing at Stanford global society. So having Bill Gould, a truly revolutionary. There were very few black professors than at any majority white school. We do have five black, predominantly black law schools.

We call them HBCU’s. And, of course, they had majority black faculties, but not any majority white school. Many people may not know, Bill came from Wayne State. He did not start his teaching career at Stanford. He had attended Cornell Law School, but he had not worked big law Wall Street or clerked for a federal judge.

These are qualifications that then were considered de rigueur if you wanted to be a law professor. And even today, many schools, especially very elite ones, may seek those credentials. And I am sure when he was hired, there must have been some people who wondered, is he gonna make it? Does he have what it takes? I hope now if any of those people are alive, they would look and think, yeah.

I guess he’s made it. He wasn’t alone in that that year revolutionary as it was. They also hired the first woman, Barbara Babcock. She didn’t have that classic profile either because women couldn’t have been in those big firms or clerking either. I was honored to have her as my professor as well as Deborah Rhode, who came right after her.

Now I want to mention, this is where I’m I’m intersecting with the prior speaker, the areas where Bill has been a role model since he hit the ground running. And from time to time, he has run. And that is as a teacher, scholar, practitioner, mentor, and race man. As a teacher, you’ve already heard, he’s taught thousands of people. He introduced sports law to the curriculum and an about courses that others haven’t taught.

Ideas about courses that others haven’t taught. You’ve heard that he’s a fabulous scholar. 11 books, more than 60 articles. If he had done that alone with nothing else, that would be truly extraordinary. And yet, he’s continuing to publish well into his eighties very calmly.

I go in that office. That’s a bit of a mess looking for where’s the leprechauns or where are the people that are for do helping produce this incredible body of work. Many professors stay in their ivory tower, writing and teaching. Bill has been engaged in what we call praxis, the intersection of theory and practice his whole career. When he joined the Wayne State faculty in 19 68, he was incredibly bold.

He said, I want to have time to represent clients. And he has done that all of these years. And you know all the institutions that he’s worked with as a practitioner, as a mediator. I mean, when I heard 300 disputes that you are, I mean, is that alone? That would be enough without the professing.

So in that area, of course, not only was he head of the NLRB. Right? But also the California Agricultural Labor Relations Board. I said, how are you going up there? Oh, I get on the train.

I go up. What? It was amazing that he had the energy to do this. Bill has been an amazing mentor to many people. I’m sure many of you in this room.

I don’t know you all. Practitioners, policy makers, and professors. So I’m just gonna call out some of the professors beside myself. We have in the house professor Ken Shropshire, class of 80, who spent most of his career at the Wharton School, and he is an expert in sports law. Just wave your hand.

We also have here, you saw him in the film, professor Gary Williams, class of 76 from Loyola, specializes civil rights law. Wave, Gary. Now, Bill came to Iowa many times since I’ve been on the faculty there. He would do a talk for us. All my faculty, they were like, oh, this is so exciting.

How did you get Bill Gould to come? Well, you know, we have something in Iowa that none of y’all got anywhere else. What is it? And I don’t mean the Iowa caucuses. We got the field of dreams.

We got the field the dreams. That’s it. So I would visit Stanford almost every year for a talk or something. And every year, I would come. Bill and I would have a lunch or a dinner or a coffee almost ever since I graduated in 1982.

Finally, Bill has been what black people call a race man. Some of you may have never heard of this term. While everything he has done has helped every type of person, among the people who have benefited a lot from his efforts have been black people. Articles, books that he has written. And to me, the triumph is the book about William Gould the first, his great grandfather who escaped from slavery and subsequently list enlisted in the navy to fight against the Confederacy.

Bill was quoted as saying, it’s perfectly proper to infuse the struggle for equality with patriotism and to be supportive of the United States. That’s the way he was. That’s the way all my forebears were, and that’s what I believe. William Gould the fourth has been an exemplar in all his roles. The very essence of excellence at this institution for more than 50 years.

Stanford just now tenured its first black woman, Rabia Belt. She could not be with us today. Also in the audience, there is a 1L, a young man I just met named Justin. Wave, Justin, so they see a 1L. Y’all remember being this age?

Thank you for coming. I hope that 50 years from now, professor Belt will have been able to influence young students like Justin and all those who will come after him for the length of time that Bill Gould has influenced so many of us. In conclusion, Bill and I were both involved in the anti apartheid movement. You saw a picture of him with the late Nelson Mandela, the first black president. Nelson Mandela thought he was in prison.

He thought it might be his life. And he said, the struggle is my life. Bill Gould has exemplified this in the struggle for justice. Bill was quoted in an article as saying, I think that the answer for young people and the answer from all of us is what Bill Gould the first did in the 18 sixties to put 1 shoulder to the wheel and try to move this society in the best way possible. Thank you very much.

Thank you. Thank you so much, APAC. Bill, Actually, Bill, come over here first. Those of you who know Bill at all know that Bill is 1 of the biggest baseball be right here. Right here.

Okay. I’ll do anything he’s saying. Great opportunity to cross Bill to. Bill, why don’t you come up here for me? I wanna make a presentation to you.

So 1 of Bill’s closest friends in the world is Dusty Baker the future Hall of Fame baseball manager and the manager of the Houston Astros who won the World Series last year. Year. Dusty couldn’t be with us today, although he wanted. He is here in spirit, but this afternoon, the Astros are playing the Rangers in national championship series and that’s it. But but Dusty is here not only in spirit, but Oh, okay.

I got a you got a good number. Number 50. I guess we gave the number of the bobbleheads for Bill, the number 50, which is kind of a numerical pun because Bill’s favorite baseball player is Mookie Betts playing for the Dodgers. And, also, this is Bill’s fiftieth year at Stanford Law School. So Dusty sends his best greetings and his likeness.

So thank you. As we were putting the program together, we interviewed scores, of associates of Bill and including many of his former students. And many of his former students have now retired. Bill, on the other hand, taught them, is still full steam ahead doing all of the things that he’s done, but doing them with you discover the fountain of youth? Well you know Alan and Truth, I’m I’m still like many of us are looking for that fountain of youth.

And I try to I’m not sure that I pursue etcetera that that I did previously. But I think that I do my best. And I of course, the subject is is as interesting to me as it was was when I first came in. You you referred to Bob Weisberg referred to the revival of sorts of that the labor movement has had. And it’s a very exciting challenging, period that we we are in right now.

And so I’m just as excited as ever not over standing by continued search. So, Bill, you are well known for having great concern for working people and their needs and the importance of their ability to organize. How did you better at this school? Well, I I got got involved because of when I was a senior in high school a very important Supreme Court decision came down Brown against Board of Education. I have had no contact, Nobody in my family on my father and mother’s side had were were were lawyers, had any contact with the law.

And the Brown Thurgood Marshall’s great success on May 17 19 54, just as I was about to graduate from high school really caught my caught my attention. The the the confluence was also the McCarthy army hearings were going on that spring, and my father was employed at Fort Monmouth which McCarthy had targeted. And I began to see that it was important for lawyers to play a role in in society in that respect as well. And all these things made me interested in in the initially, I wanted to work for the NAACP but I discovered very quickly that the Thurgood Marshall had a staff of fourpeople. There was no such thing as civil rights law at that time.

Brown was of course, this lonely group of of lawyers Charles Houston being 1 of them, were had battled on and produced a Brown. We had chief justice Warren come here when Tom was Tom Rollers was dean, and 1 of these pictures shows that. And and so I I became interested in trying to translate this interest into something beyond being on the staff of the NAACP. And I found at that time that the industrial unions in particular seemed to espouse principles of racial equality I became very much interested in and I and I had I worked I was represented by some of the CIO unions when I worked as a laborer. And Iso I had it in my mind that maybe this was the way to this is the way to go.

This is the way I could realize some of these some of these some of these goals. And as dean Wing pointed out, you not only were an academic but you were a practitioner. And 1 of the most important cases in your career and a landmark case was Detroit Edison case. Can you tell us about the role in your career of that case? Yeah.

That was a case that arose when I was on the faculty at Wayne State. I was very friendly with 1 of my colleagues called called Moke, Jack Moke. I represented him. I began to do some I probably did at Wayne State is I was in court as much as I was when I was in private practice. And I represented Jack, actually when he wanted to get on the ballot.

Jack after the upheavals of 1967,19 68, Jack was involved in New Detroit, which was trying to see if they could extrapolate from all these terrible bunch of workers from Detroit Edison came to see Jack a bunch of workers from Detroit Edison came to see Jack and he said they they said we we’re being discriminated against in a number of respects. He said, well, I got a colleague you should go and see. And he had them come to see me at the law school. And I really didn’t wanna get involved in this because I had a lot of things going on at that time. But they sat there and set forth for me really a list of everything that I was discussing employment discrimination law.

I have acted as a consultant for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in the mid sixties. And everything that we were dealing with, these guys were talking about. And so they kept coming back, and I agreed to represent them. And I began to see this case as maybe a vehicle to establish important remedies. Law professors, we we are very much interested in the case law, the circumstances under which liability can be imposed, that’s terribly important.

But around this time, I was becoming very much interested in effective remedies for fair employment practice law. And I thought that maybe this was a case which would be a vehicle to do that. And we tried the case over a substantial period of time. And the district judge, judge Damon Keith in Detroit awarded us a so called front pay as well as back pay, that is to compensate the workers for in the first instance. And he also fashioned punitive damages, remedies, and we got various kinds of equitable relief.

Well, you know, it was like a it was a this is a very exciting period of time. We went to the court of appeals to the sixth circuit. The Edison, of course, appealed, cut back on some of the remedies, took our punitive damages away. But I often thought that they just couldn’t write fast enough to take away everything that we obtained at the district hundred 400 people 400 people in excess of 5,000,000 dollars, which at that time was the highest per capita judgment ever ever obtained in an employment discrimination case. So we we we’re very fortunate.

My the American Civil Liberties Union, my friend Mel Wolf, who was the legal director, financed us. He said now he said we’re gonna we’re gonna pay your way, because I was operating by myself, then I brought a couple of other people in. No way could we sustain a case like that with these guys who have no money. Proposal. If you prevail and you get attorney’s fees you have to give them to me.

And and we got them. We got we got a quarter of a million dollars, which was big money at that time. And the the ACLU got it. So I think I think we were able to make some progress along with other people who had were taking cases like this up at that time. This was the 19 seventies.

It took a decade to bring this to conclusion. It was a long period. Started at Wayne State, continued here at Stanford. I would fly out from San Francisco to Detroit, argue all day the next day. I was that’s something that’s something I can’t do today Adrian.

And and but I I would get in my hotel 11 o’clock at night, argue all day the following day. And we’re able to I like to think we’re able to accomplish some good through that and perhaps some ancillary cases that came about as a result of that. So so when Bill says that there’s things things that he could do before that he can’t do now, he he’s lying. Because when we have had to set up meetings over the last year and putting this together, the person who we always had the hardest time of tying down in his busy schedule to meet with us by Zoom was Bill. He was all was doing something.

And as I said, he still has that same energy. So after practice, they knew them, became a professor at Wayne State and then a professor at Stanford Law School. And how did you decide to become a professor? And and how did it impact your career when you came here to Stanford? Well I decided decided to I hadn’t really planned on being a professor.

Adrian was pointing out that that I didn’t really fit the criteria. But I had to have the I was doing a lot of I was writing for a lot of law journals. I was writing I had ideas about my subject. And I was writing a series of law journal articles at that point. Also, I was writing for periodicals, sometimes involving civil rights law, sometimes involving politics for magazines like Commonweal, the Roman Catholic Magazine, The New Leader, and The New Republic.

I think they showed my check, the first check I ever got. They paid me, I think, 15 dollars for the my first publication when I reviewed Alan’s Alan Peyton’s Hope for South Africa, who wrote those two great novels before it. And I just Africa who wrote those two great novels before it. And I just as if they didn’t know me, and I just wrote this piece and sent it in. And so that led to so so I got a call out of the blue, really.

Of course, the cities were burning and institutions were now suddenly interested in finding black academics whereas and so they they’re looking beyond the traditional criteria. And I got a call out of the blue from an assistant dean at Wayne State Law School. And I remember saying to Hilda that my wife Hilda, who’s I I said, you know, there’s just no way that I had a lot of pals in Detroit most to even today. You know, probably of my friends are in Detroit and but from my UAE, my first job was with the United Auto Workers in Detroit. I said, but there’s no way I’ll l do that.

But then I went out there and they said, you know, you could you could teach what you want. You could write. You can arbitrate. You can represent people in court. Well, I and and and at that time you know, there wasn’t this vast financial gulf between academic and law practice.

And and so we we just we went out there. And and then I got another call when when I visited at Harvard in the fall of 1971. And as soon as I sat down on my desk, I got a call from a fellow who named Mark Franklin, who was on the faculty here for a number of years. So I think he was chairman of the committee. And he said, we’d like you to come out and talk to us.

And I think I’d only been to California twice in my life at that point. I really my my father had been out here I got out to California a number of times. During the war he my father set up the set up the radar to guard against Japanese incursions. And he went up and down the coast of California. He knew it pretty well.

Talked to him about it. And we just we came out here and we met a number of people. We met a guy who’s Jim Dana very you know, I was really very much taken very you know, I was really very much taken with it. And Tom Ehrlich, he was the dean, and Tom was very much was interested in in me and and I felt very supportive and and supportive when I came here. And so we we came here to we said, you know, this is this seems like a great place.

We we and we bought our house down in 711, Salvante, a couple blocks here from the law school, and I’ve been here ever ever since. This is great being being with you, Bill, and I’m Dick Morningstar, Alan’s classmate. Alan, do you wanna give him your microphone? I supposedly have. It’s fallen down.

This is why you couldn’t hear me because of Yeah. My jacket. Any event I had I was saying that Alan and I were classmates in class of 1970 and I get to talk about maybe the most serious part of the program sports and baseball. And, you know, Bill and I have Stanford Law School in common. We have excuse me, Red Sox fan in the world.

And excuse me, Red Sox fan in the world, and Bill Bill is the first. And I can say that Bill and I are probably the only people in the world, literally, who, as we did a couple of days ago, could come up with the names of Norm Zouchin and Dick Gurnard in a heartbeat. So in any event, we have that very much in common. But I would like to ask you, Bill how did you become such a sports fan, such a Red Sox fan? What is it what is it meant in your life?

Life? I know it’s been very painful sometimes for both of us particularly particularly this year. But how did this all happen? Well when I was about 9 turning 10 I fell in with a bunch of guys and we started playing baseball together. We had no umpires.

We had there was no there wasn’t even a uniform distance between the bases. And we played every day, day, all summer, morning and afternoon. Our our mothers made sandwiches for us, and we we we this is all this is all consuming. My father thought this was a little bit out of control. Why?

Because we not only we play every day, play all summer, but we we began to become interested in we get to we read we’re gonna read about it. We read the newspapers, we listened to radio. There was no television. There was no television until a year or so later. And this was we ride on our bikes talking about it.

To me baseball in particular, you know, and I know they say this about what the world calls football, what we call soccer. Baseball is the is the beautiful game. It’s it is it is like it’s like ballet. It’s it’s it’s so the the things that these guys can the really good people can do out there. And there is something about the ambiance.

You know, when my father and I first went if I remember, my father took me to my first big league game that summer. We we we were so impressed how the cognoscente could tell who the pitcher was coming in from the bullpen. You know, those days, nobody ran in from the bullpen. They that was they were too dignified. They walked in a slow stately way and and we we but their cognitive setting knew who as the gate swung open, they knew who was coming in.

And the the the ambiance, the the way the the motions of the players, the theater and the fact that the game goes on on forever, could go on forever. And this is, you know, if you read Kinsello’s novels, you you see this he makes much of this games that go on for for for days. Then there was something else as well I think in those days, I pity I’m ashamed of the fact that I’ve lost this characteristic over the years. I was very good at math. And there was another guy and I, we were a year ahead of the class.

We were the teachers had us going we had a a year and a half ahead of where the class was in math. I love computation. I loved and you know, I love statistics. Well, of course, and, you know, you’re batting averages. Of course, we I don’t understand many of these new kinds of statistics that have been introduced recently.

But batting averages just an ERA’s, you know, we knew why ER earn run averages was so important. It’s just a part of our it was in our bones, part of our existence. And it was all consuming. You know, my my wife, Faith, is in the audience here. And I hope you have taken to heart listening carefully to Well, Hilda, my wife, Hilda, doesn’t What Bill said?

And have the same feeling that faith has. She has the same feeling that Faith has. But, you know, your words are reminiscent to, you know, the late Archie Mariam. Baseball is a beautiful game. Remember that, Faith.

You know, there’s been a lot of talk already about your time at the National Labor Relations Board and and the baseball strike and that you were as chairman led the board in bringing suit from John DeGruv to effectively stop stop the baseball strike. And I know some say, well, he’s a baseball fan. That’s why he did this. Well, you know, we also have to remember that the judge who granted the injunctive relief was then judge Sotomayor which is which is pretty pretty impressive. Tell us, you know, tell us a little bit about that experience and how you, you know, how you feel about maybe you’d be too modest to say that you saved the game, but how you feel about all of that?

Well, I of course, I didn’t save the game. I was 1 of the people that maybe was instrumental in in bringing that strike to a conclusion in the in the spring of 1995. You know, the the season really got off the tracks in 1994, the year the year that I went to Washington with the players, I think, thought that they could strike the owners toward the end of the season and that the owners would would capitulate. And much to their surprise the owners didn’t do that. And they canceled the World Series for the second time.

First time since 1904 that that the World Series have been have been canceled. I I you know, I remember I was doing some salary arbitrations in baseball before I took that job at the NLRB. And I remember saying, oh, gosh. What a shame. I’m gonna have to give up all these salary arbitrations.

And I was teaching the sports law course with a fellow named Leonard Coppet, who said to me, wait till you get to Washington. You’re gonna be right in the middle of it. Well we had unfair labor practice charges filed with us by the players against the owners. And the the question was whether or not the owners had refused to bargain in good faith. And there’s an obligation under federal labor law, the National Labor Relations Act, that you must bargain on all subjects, so called mandatory subjects to the point of impasse.

That was students always say, what is that? What and what does that mean? And I try to tell them some stories to which we don’t have time to do here, but as to what impasse means. But the owners had taken the position that they had changed certain conditions of employment. They had taken the position bargain to the point of impasse.

And so we we found that they had there was reasonable cause, to use the words of the statute to find that they have bargained in bad faith. And on the basis of that, we used a provision of that, but at that that time was little little used, which gave us the authority to go into federal court. Judg,eas she was then, Sotomayor, held in our favor and as did the judges at the Court of Appeals for the second circuit when the matter was appealed later in the year. And the players came back to the field once they got that ruling, and the the season began and was continued. And eventually, the parties negotiated a collective bargaining agreement.

So we we I think it it it was a an initiative that worked out pretty well in the sense that it got the season going and gave us a a baseball that we many of us want. And but it but it it was done, I think on the basis of proper examination of our of our duties under the National Labor Relations Act itself. I think we’re maybe beginning to run run a little short on time, but let me ask you 1 more sports related question, which is your famous class in sports law and how that happened. You had coming to your class people like Dusty Baker, Al Attles, Willie Mays actually came to 1 of your classes. Yes.

How how did that all happen? And 1 of the things that when we interviewed with with Dusty was saying that, you know, he learned more learned more from the class and the class, you know, learned from him and the importance of players who he introduced you to seeing you as a as a prominent prominent African American scholar and how important that was to so many people. Maybe you can comment a little bit on that class and how you felt about it and the relationships that you made from that class. Well, that class was something that began in the mid eighties. A colleague of mine from Wayne State and I, and he and I had much contact when I went when I visited Harvard, he was at Boston College.

We had talked about putting something like this together and writing about this. We ultimately wrote a book about sports law together. We we taught a summer school in the first cut on this was a Golden Gate Law School in the summer of 19 80. And as a result of this, we and then I met these 2 other fellows who had different different strengths. Leonard Coppeth, this journalist, who was a sports journalist from the New York who had been with the New York Times.

Alvin Adels, who had been you know, a great basketball player for the Golden State Warriors and their coach who coached them to a championship in the mid seventies. And very different looking and acting people. And any of you who have ever seen either mister Coppin or or or mister Al. Although, Al and I, exact same we used to call each other twins because we’re exact same same same age. So we we put together a lot of materials on of labor, you know, the ant initially, the antitrust cases were very important, the contract cases.

Labor began to become important in large part, initially, due to the baseball players, the the the arbitration system that they put into effect. So we put all these materials together. We had a cast of thousands. We had a cast of many guest lecturers. 1 of them was we had we had Larry Whiteside from the Boston Globe.

We had Bill Duffy, the sports agent. We had Dusty come Dusty Baker who’s been in the seminar a number of times. And we had Bill Walsh who came in. It was just really terrific. The baseball coach, the Stanford baseball coach Mark Marcus, who became a good pal.

And and 1 day we had Willie Mays and you know, the electricity kinda went through the law school that day. And Willie was Willie was Willie. And he said things some things that I couldn’t say or they did the good my good deans would have me dismissed, but but but but he he was great. And think the students enjoyed it because it brought together the technical material, the the the labor law, the antitrust, the contract live personalities that they were familiar with from from afar. Very fun.

Yeah. We got So, Bill in your 50 years at Stanford Law School, you have educated and mentored so many students. And the students that we talked to in preparing for this will talk about how you made them you find the excitement of labor Bill Gould suggested to them different Bill Gould suggested to him different courses in life, that you’ve stayed in touch with them over the years, that they say that you have great empathy for their academic and their personal needs. And then when they needed assistance, I’m very appreciative of of those kinds of comments. I think as my wife would tell you you know, there’s this character most of the students seem unfamiliar with him these days called mister Chips.

Mister Chips. I a mister Chips, I am not. Mister Chips was a wonderful character who just was involved deeply. As as my colleague some of you may know him Herman Levy at Santa Clara Law School. He was mister Chips.

Mister Chips said enough. But I I have I have you know, I have a a passion for what I’m doing, and I and I do have have been able to form I think reasonably good relationships with a number of students over the years. You know, as I was thinking about this talk this afternoon, I was thinking about all the those that it’s impossible really to to catalog them and except that I think those first few years, you had 1 of them up you got a couple of them up here. Those first few years, of the the triumvirate, you know I don’t know if he’s here. Oscar Rosenblum, who was my very first research assistant here.

Then Jeremiah Collins, who you saw here, and Gary Williams, who you saw here as well. So I feel as though you know, there are a lot of them that I’ve had a, you know, a great deal of contact with. I wish I could have brought more of them to Washington and Sacramento with me in these 2 But I suppose the the ultimately, there is a you know, this is all we can do. We can we can try to pass something on that we have and try to make their lives better and enrich them and as and we hope that we can do that about society generally. And and I think being here at Stanford Law School has given me a real chance to do that with these very smart just amazed to, you know, the number of the these kids over the years.

I still call them kids, you know. They they they who even though some of them are retired who have been who have been working with me and who I’ve taught whether they be research assistants or not. One last question from me is that you are amazingly prolific. You have written 11 books. Right now, you are working on your twelfth.

If you could turn on your TV or your radio or look in the press, and there’s an article about a labor law issue, is that almost invariably there’ll be a quote from the go to guy from the people on the press and the media is that Bill Gould will explain the complicated labor law question in layman’s terms. What’s it like to be relevant after this? I’ve I’ve been I’ve been here. I don’t wanna press my luck here. They but you know, I think that 1 of things that 1 of the things that we can do you know, I I gave a lot of talks abroad.

I taught abroad at South Africa. I’ve spent a lot of time in Japan. And to make a a long story short, I I saw that there was a great need to explain this subject in to to boil it down, to make it understandable that this is what we’re supposed to be doing. And my wife said to me, you know, why don’t you write a book like that? Okay.

Alright. So that was that’s that’s how this book, a primer on American labor law came about. And that’s how the only 6 editions, but starting in 1982 and going through 2019 came about. About. And that that was my attempt to really I suppose, be relevant in that sense and to make the subject you know, to to remove some of the some of the obfuscation that otherwise is associated with it.

One last question. Okay. That’s based on the rest of the agenda. We have one last question, then we have a very special presentation, and Bill will make his closing comments. And the last question related, you mentioned that you your experiences in Tokyo and South Africa and your relationship with Nelson Mandela.

Maybe a few words about that and how that might have affected your work here. Well, those are in terms of I I think I was able to bring some of that back here. You know, when I came back at 1 point in the nineties from 1 of my visits to South Africa I actually taught a seminar on the constitutional negotiations in in South Africa that I was involved in Cyril Ramaphosa, was just a little young guy sitting in our house having lunch with us in the early eighties. And and he I go back in the nineties, and he arranges for us arranges for me to to sit in on the constitutional negotiations. So that was terribly important.

I think that Japan you know, I was I had an interest in Japan since I was a a child, since we were attacked by Japan. And I remember my father, very patriotic friendly, but my father said you know, the United States is taking a beating in this war because they thought that the Japanese were monkeys in the trees. That’s really true. That’s really true. They thought the the Japanese were monkeys in the trees, and they can’t fly fly planes.

Well, you know, see, Japan did all these extraordinary things, and I was just really I that that made such such an impression on me and then, of course, Japan became so successful in the sixties after the war, the seventies. So I had to write a book once particularly when I found out that Japan operates under the same legal labor law system that the United States devised at the end of the war. MacArthur imposed that upon them. So but it’s a very, very different society. That that was really what my time in Japan was about.

South Africa goodness. So that was terribly exciting. And when I first went there, the name Mandela could not be mentioned. And I became some of those photos are with these guys that I met in Soweto and that I met when I first got there and the community of the resurrection father Huddleston’s you know, father Huddleston wrote, not for your comfort. The I went out to the community of the resurrection and met with these guys who were shop stewards and trade unionists who lived in Soweto.

And I became very friendly with them at that time. Very exciting time and, of course, very exciting to be able to come back as I did not only during the constitutional negotiations once Mandela was freed, but then when when the new system, the new government I do have something very special very special to read. Okay. Close to my mouth. Okay.

I’m gonna read this. It reads like this. Dear Bill, I’m delighted celebrate 50 years on the faculty of Stanford Law School. Throughout your legendary tenure, you’ve dramatically advanced the study and practice of labor and discrimination law, helping to make our nation fairer and stronger. Along the way, you have earned the respect of all who know you for your passion for the passion for the law, your academic scholarship, and your generous mentorship of countless students.

Of course, I will always be grateful that I could convince you to spend 4 years in Washington as the chairman of the National Labor Relations Board. Your outstanding service brought new vision and purpose to the NLRB at a time of momentous economic and social change, and millions are better off today because of it. And perhaps most of import most important of all, you saved baseball. Thank you for all you’ve done throughout your life and career to move America forward. You have my very best wishes for many many more years of health, fulfillment.

Sincerely, Bill Clinton. Oh, wow. This is really terrific. Okay.

I’m on. Okay. Well, the the hour is late. Well, let me begin by saying how much I’m appreciative for this very fine day and to the individuals who made it possible, particularly the guys who really day and also went through the process of putting it together. Richard Morningstar of Massachusetts and Alan Pick here in California from Los Angeles.

I didn’t know either of them before this process began. And although I had contact with them when Felton Henderson was honored a year or so ago. But aside from that, I really didn’t know them and I I’m I’ve developed a real sense of camaraderie with them in the process of this this day. And I thank them for for it. And I also wanna thank Tom Ehrlich who’s here today who was the dean of the law school and really responsible for my coming to Stanford in the fall of 1971 to be interviewed for this job that I’ve held all these years in in when he was a a dean, he was my first dean.

And my favorite dean, He and I have remained close over the years, and we continue to meet periodically here to this very day. And the other dean that I want to mention as well as Paul Bress who played such a role in making it possible for me to do the research and travel that I wanted to engage in in South Africa in the 19 nineties. This led to my returning there for president Mandela’s inauguration. And prior to his inauguration, Ramaphosa who today is the Ramaphosa who today is the president of South Africa and at that time was a leader in the African National Congress, a leader in the mine workers first. The all of this begins in the fall of 1972 when I came here.

It was a big momentous move for me because although I have traveled to California a raised in raised in New Jersey, and really was until coming here in 1972 an Easterner. And I know my parents in particular were concerned about this great distance between that now I would have between California and where they resided in New Jersey. I wanna thank this day, my parents in possible for me to to do the work that I’ve done over these years to live the life that I have lived. And without my parents and that environment I don’t think this would have been possible. They they believed in me, and they inspired me to go forward and to try to do the best I could to make change wherever it was possible to to do it.

And they really gave me my my start in life. My wife, Hilda who has been by my side through all of these years and really running 711 Salvatierra Street where we’ve resided all these years since 1972 and playing probably a maybe beyond middle aged, young men who grew up at 711. And of course, I want to thank the oldest of them William Gould the fifth for coming here with his wife, Doreena, and with their 2 children Alina my first our first grandchild, first grandchild who was a a young woman all the others all my sons, of course and 3 of my 4 grandchildren have been grandsons and not granddaughters as Alina is. And it’s great to have her here as well as her brother, William Benjamin Gould, the sixth and how proud we are of them all. It’s hard to believe that this period of time has gone by so quickly.

I think first of the many students that I’ve had over the years and it really would be impossible to to mention them all. I won’t try to do that. Then I just will make a slight departure from that by mentioning a few of the ones who who are with me at the very earliest stage stages of my work here in the seventies and the very early eighties. My first research assistant who’s here today Oscar Rosenblum of Palo Alto whom I met when I first arrived now a professor of at Loyola Law School. And he has been a lawyer for first, the agricultural labor relations board in Sacramento when it was first established and how brave he was and how proud I am of his service to the agricultural board, which I later became involved with in in this century.

Gary was there at the beginning and played such an important role there. And then later on, with the American Civil Liberties Union with which I’ve had a good deal of contact over the years. And Jeremiah Collins, who’s become the doyenne of of Supreme Court labor law advocates in this century and has had such a distinguished career at the Brethoff and Kaiser law firm in Washington, DC. And then as well Karen as I had seemingly endless responsibilities in the early 1980’s. She worked with me in 19 80 and 19 81 and when I was the secretary of the labor and employment law section of the American Bar Association.

So they’ve all been the students have been the at the heart of my experience here at Stanford Law School over the years. I I came into a world of law teaching really not by design. I had no intention of becoming counsel for the United Auto Workers, a junior attorney, counsel for the United Auto Workers, junior attorney with the NLRB in Washington in the mid sixties, and then in private practice in New York City. But I was interested in my subject, and I wrote about my subject. And that combined with the tumult of the 19 sixties, which made law school suddenly interested in having here when there had been none before led to my invitation to coming here.

And it it has been a it has been in the essence of it has been a very good experience for me. I’ve been able to to write. I’ve just finished my twelfth book and written numerous articles for both law journals and newspapers and weekly periodicals as well. And teaching experience, which I’ve alluded to the ability to research, and also the from the beginning, I was allowed as I was at Wayne State Law School where I first began in Detroit in 1968 as a with my first teaching job to arbitrate and mediate labor disputes and to be involved in civil rights cases including this 1 this this mammoth 1, this class action stamps against Detroit Edison, which led to unprecedented monetary recoveries for the class. At that time, the greatest in terms of monetary recovery, back back pay, front pay.

We didn’t get punitive damages in the final analysis that had ever been provided by any court in a case involving title 7 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits racial in our society. It was one of the crowning achievements of of our country in in 1964. And then the the opportunity National Labor Relations Board and the people who were responsible for that said to me, well, this really all of your most of your work, although you’ve been involved with arbitration and employment discrimination, involves the National Labor Relations Act, it’s logical that you that this would be an important thing to for you to do. And I had a very interesting experience there in Washington for four and a half years as chairman agricultural labor relations board here in Sacramento being invited to take that position. I took it for 3 years invited by governor Jerry Brown the second time around.

So it’s been a it’s been a a great ride and 1 that I’m proud of and 1 that I’m grateful for looking at the people that I’ve mentioned here today. It’s something that I don’t regard as finished. I hope to continue in the years to come as long as I have the physical and intellectual ability to do so, and I thank all of you very much much for this opportunity to be here and for the wonderful honor that you’ve been bestowed upon me by making this day possible. Thank you very much.

Professor Gould is an unforgettable professor. His brilliant mind and passion for labour law/sports is unparalleled. I had the honor of having him as my Masters thesis advisor and I learned so much from him.

Congratulations Bill on this wonderful achievement!

Melanie Vipond, JSM '10

50 years at Stanford Law School means I know you more than 50 years, succeeding you at Battle Fowler. We overlapped about three weeks, which included a Mets day game at Shea Stadium using the Entenmann’s box, one of the firm’s most fun clients. I knew I was going to love at least some of that job. I also recall vividly one winter day when my wife and I visited you at your law school office. I had been a Teaching Fellow at Stanford Law School about 10 years before, and my wife wondered why I was at Battle Fowler in NYC and you were in warm Stanford. Anyway, the best to you, and continue all your good work.

Dick Adelman

I did not have Professor Gould as a teacher at SLS, but I got to know him later in my career, when I became interested in becoming a mediator and arbitrator. Professor Gould most graciously assisted me in exploring opportunities to arbitrate, and we shared several things in common: Boston, rooting for the Red Sox, an interest in his family’s history and the memorial installed in Dedham, MA. Professor Gould combines all the attributes I admired in my Stanford law professors; tremendous knowledge of his area of specialization; great interest in his students; and the ability to communicate positively with those students to enable them to enthusiastically pursue their own areas of interest.

Thomas Elkind, JD ’76

Professor Gould was one of the highlights for me of SLS. He is a brilliant scholar and a class act. I took his Constitutional Transition of South Africa class and was astounded by his deep knowledge of the history, issues, players, and the path forward. I learned so much from him and have had an abiding interest in South Africa ever since. He also treated the class to an MLB game, and it was a joy to see his passion for the game and ability to recite stats on everything! Of course, I was elated to see him rightfully honored with his appointment as Chairman of the NLRB successfully bringing the baseball strike to an end. Perfect timing of his appointment. Play on, Professor Gould!

Thank you, Professor.

Samantha Rijken Begovich, JD ’94