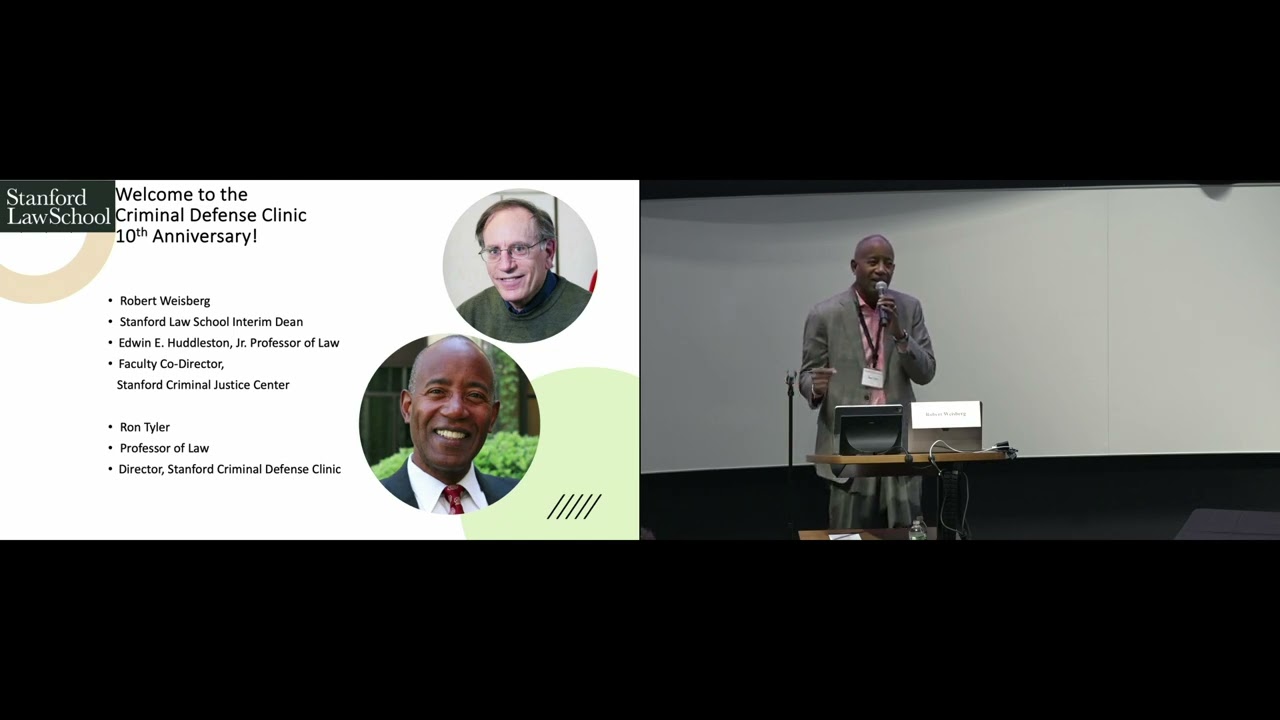

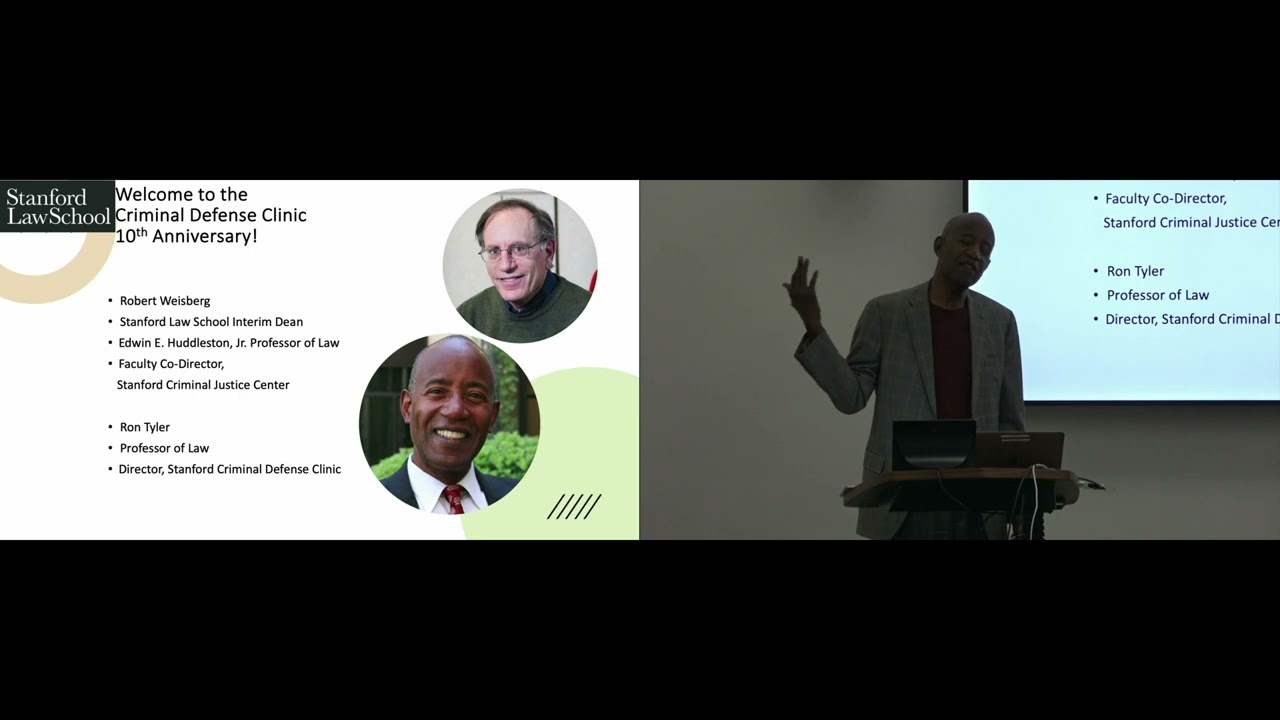

Criminal Defense Clinic 10-Year Anniversary Celebration

On November 10 and 11, 2023, the Criminal Defense Clinic welcomed alumni, faculty, staff, organizational partners, family, and friends to celebrate, connect, and reflect on a decade of clinic accomplishments.

Attendees gathered on Friday, November 10, for a cocktail reception hosted by clinic alum Katherine Lin, ’14, and Ben Maurer. On Saturday, November 11, guests gathered at Stanford Law School for three panel discussions, addressing emerging topics such as impact litigation, movement lawyering, and sustainability/wellness for lawyers. That evening, CDC hosted a dinner celebration, with special remarks by Clinic Director, Professor Ron Tyler.

Thank you to our guests for celebrating with us.

Cocktail Reception Hosted by Katherine Lin

Introduction and Panel 1: The Best (Criminal) Defense is a Good Offense: Collaborative Impact Litigation

Okay. I think we are going to begin since I’ve turned on the mic and I’m looking at you and I’m looking at my notes. It must mean we’re beginning. I’m so glad to see you all. As you all know, I’m Professor Ron Tyler, the director of the Criminal Defense Clinic. And on behalf of the entire Criminal Defense Clinic team, I’m really delighted to welcome you to this celebration of ten years of the Criminal Defense Clinic.In a moment, I will invite Dean Robert Weisberg to give us some remarks. But, but first, first to this. This month, November, is National Native American Heritage Month which is a federally recognized period in which we honor native communities. We honor their cultures.We honor their traditions. While raising awareness about the unique historical and present day struggles of indigenous people in the United States.

There are approximately 7 million indigenous people living in the United States. And California has the second highest population of indigenous people. For thousands of years, indigenous people have lived in the region that we now call the San Francisco Bay Area. And in spite of, in spite of, genocidal oppression, By the Spanish, then the Mexicans, then the Americans. In spite of all of that, the Ohlone have persisted. Generation after generation, they are still here in the Bay Area. They speak to us. Shall we listen?

Good day. My name is Charlene Nijmay, and I’m the chairwoman for the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco Bay Area. Here with me today, I have Vice Chair Monica Arleano, and former Councilwoman Gloria Arleano, and Muwekma youth Isabella Gomez, Georgiana Gomez, Lucas Arleano, and Gabriel Nijmay. Today, we will be reading our land acknowledgement on behalf of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe.

Thank you and welcome to our ancestral homeland.

[Subtitles translating Muwekma into English are in the pre-recorded video]

The subtitles, they’re sometimes hard to read, so I’m going to restate in English what we heard in Muwekma. Stanford University recognizes that it’s located on the ethno historic territory of the ancestral and traditional land of the intermarried Puichon Thámien Ohlone-speaking People and the historic, sovereign, previously federally recognized Verona Band of Alameda County, presently identified as the Muwekma Ohlone tribe of the San Francisco Bay Area. This land was and continues to be of great spiritual and historic importance to the Muwekma Ohlone tribe and other familial descendants of the Verona Band. We at Stanford recognize that every member of the greater Palo Alto community has and continues to benefit from the use and occupation of this land since this institution’s founding in 1891.

Consistent with our values of community inclusion and diversity, we have a responsibility to acknowledge and make known through various enterprises Stanford University’s relationship to Native Peoples. As members of the greater Palo Alto community, it is vitally important that we not only acknowledge and commemorate the history of the land on which we live, work, and learn, but also we recognize that the Muwekma Ohlone People are alive and flourishing as members of the Palo Alto and broader Bay Area community today. Aho!

Thank you all. Dean Weisberg, I will take my little placard off here. So this must be you, and I’m asked to remind you to hold the mic like so. You too, and this way, right? Hello everyone. I’m, I’m delighted to be here. I, I think I’m here because I was invited in my sort of ex officio role because I was asked to serve as interim dean.

It’s just as well that I got an official invitation because it would have saved a lot of embarrassment because I think I would have barged in anyway without an invitation because I of course teach criminal law and criminal procedure and although I’m not part of this great clinic, I’ve always thought of myself, and I think this is true of others of us who are on the criminal law side of the faculty, I’ve always thought of myself as sort of criminal defense clinic adjacent and I’ll say a word about one more word about that in a second, but I just want to make a kind of historical and institutional note.

Even before I do that, just a a note about construction. I’m sure a lot of you remember. Room 290. This is room 290. It just doesn’t look like it. It took about a year and a half. And if you remember, 290 is this rather dank, dysfunctional, oversized room where if we held a class in it, you know, and the students would, you know, do what students do, sit in various places, it would look like The right field bleachers in a baseball game when the home team is losing seven to nothing in the eighth inning.

Okay Anyway, a lot was invested in turning it into this beautiful modular room We can make it bigger smaller and we have all the great electronics. So that’s wonderful and another construction note if you go back to our wonderful, well, now about 10 year old clinic space across the way. It sits under our wonderful patio. And that will be a wonderful patio again pretty soon. But if you haven’t gone by lately and if you look at the patio, you will see something that looks like a cross between Roman ruins and a bad skateboard park. But that’s because it turned out that the beautiful foliage, which enhanced the patio came with this element, which I think is called water and plumbing wasn’t done very well, but it’s all going to be restored anyway.

So I just wanted to mention that the historical note is that I’ve been at Stanford Law School for zillions of years and way, way back, what was called the clinical program was really not much of a program. It was kind of a loosely linked and sometimes loosely supervised bunch of externship activities, some of them linked to, you know, situations within the law school and sort of all over the place and without a real clinical faculty.

Things got transformed, oh gosh, it must be about 16, 17 years ago when Larry Marshall was brought here. And then we developed the clinical program which we have now, which I think is a model for the entire country. And a key premise of it was that we weren’t going to simply announce, well, we’re going to have all the standard clinics, let’s find somebody to run them.

Rather, what had emerged was a whole concept, a revolutionary concept of clinical education as a form of pedagogy, a form of education, and we were looking for the best possible clinical professors, and we would build new clinics around those people. So, for example, the first of our clinical professors was our great colleague, Bill Koski, who teaches our education rights clinic, and that wouldn’t have been the most obvious clinic to start with, but we started with Bill because he was such a leader in, in the field of clinical teaching.

Now, I think it was pretty clear that before too long, we were going to have a criminal defense clinic. That just had to be true, but it’s not as if we just said, okay, let’s have a criminal defense clinic. Let’s find somebody to run it. Rather, by that point, we were committed to finding the best clinical educators.

People coming from practice who were already very thoughtful and knowledgeable and very creative about clinical education. So, we set out to find such people, and for for in terms of the criminal defense clinic, we were either incredibly brilliant and smart or incredibly lucky to find Ron Tyler.

And, you know, the rest is is history, and of course Ron has been equally brilliant and creative in finding such great partners as Suzanne, who I’m delighted to see here, and now Carly. And getting back to the, what I’ll call the criminal adjacency of those of us on the non clinical side of things I have benefited tremendously from there being a clinic in part because Ron and his colleagues are such criminal law experts that we talk to each other about issues all the time. And I’m not sure if they learn much from me, but I learn a lot from them about things that I can really incorporate into my teaching. And I also find it especially educational to talk to my students, students who have been in or are currently in my criminal law, criminal procedure classes, but who were in the clinics, who sometimes come to me for a little guidance on some obscure doctrinal issue, but frankly, once again, I learned more from them in that mode than than they learned from me.

So in any event, I think the clinical program on a whole has been a great success in terms of being integrated into a core part of Stanford Law School. And I think the criminal defense clinic is really a model within that model, really. Of great success in that regard. So 10 years, oh my gosh time flies when you’re having fun, but time also flies when you’re doing justice and that’s certainly what the clinic has done. So I congratulate everybody involved and I hope you enjoy this great day.

Thanks.

Okay.

So.

I’m trying to take this all in some of you, in fact, many of you were with us yesterday evening as well when we were at the home of clinic alum Katherine Lin and her husband Ben Maurer. They kindly opened their home for us for a cocktail event to start this all off. I’m so pleased that we have the opportunity to do this, that we have the opportunity to be together.

In attendance we have Criminal Defense Clinic teachers, staff, alums, current students, we have SLS students, allied with criminal defense. We have members of our collaborating offices from the Santa Clara County Public Defender’s Office, from the San Mateo Private Defender Program. We have the new Chief Assistant, John Ellworth. From the Federal Public Defender, we have the Chief of the Appellate Division, Carmen Smarandoiou. We have teachers and staff representing the 11 Mills Legal Clinics, some of the teachers and staff. And we have members of the broader SLS community.

So today, today we celebrate these 10 years of work dedicated to the twin goals of preparing law students to enter legal practice and of providing high quality indigent defense services to our marginalized neighbors.

In room 270, our socializing space, you are treated to images of our decade striving together with a backing soundtrack of that’s suggestions from you, our attendees. I had a delightful conversation with Gisele of programs about, well, you know, some of those we could have used the radio version. I said, no, no, no radio versions, . I want the uncensored stuff, goddammit. We’re public defenders, so that’s what you’ve got. So be beware, be ready, . So now I’m like going off script here, so, you know, I think about all the fights, when you look at those pictures, it makes me think about so many fights that we’ve fought. So many lives that we’ve touched. So many stories that we’ve told. During our 15 minute breaks between panels, really feel free to ask any CDC member about their experiences. The trials early on, the evidentiary hearings, quite common, the oral arguments, the stellar written motions, and more.

Today’s program will provide us with an opportunity to discuss some of the work of the clinic and of our collaborating partners, as well as to reflect on wellness. You probably received a program at registration but I will briefly review also for the benefit of the many alums who reached out and said, I wish I could be here, but I can’t.

Is there some way that you’re going to have this recorded? Yes. Okay. We are. Yes, Dean Weisberg, as it turns out, all those things you said are recorded now for posterity. And also that’s a warning for all of you. If you’re giving comments, which I hope you will, just know that it’s all going to be recorded, not in 270, but yes, in here.

And yes, for the dinner event in 270. So With that, let me talk about our lineup for today again. It was in the material that you received, but for the benefit of those who are going to be watching this as a recording, our first panel will be the best criminal defense is a good offense. We’ll be talking about collaborative impact litigation in that panel.

We’ll then have a 15 minute break, followed by lunch in 270. Then, in the afternoon, we’ll have two panels. The first panel in the afternoon will be a movement lawyering panel where we’ll talk about the work centering impacted communities, which is, of course, what the criminal defense clinic has always done.

After a break, we’ll move to the third panel on resiliency in the work, getting real about burnout, sustainability, and wellness. And then after that third panel, it’s got to be five o’clock somewhere. At four o’clock, we’ll have cocktails followed by dinner. And we’ll have some some programming at dinner, by the way.

Some that was planned and some that’s just in time. So I’m looking forward to that. So with that, we’re going to set up for the first panel. So panelists, if you’ll come forward and then we’ll return with introductions.

All right. So for our first panel. Oh, sorry. Pardon me. Just, just a moment.

I forgot this part. A little embarrassing, sorry.

Oh yeah. How many layers do you have?

All right, there.

Yeah, bail is ransom, damn it. All right, so, the first panel I’m going to introduce our, our facilitator, and then she will take it from there. Our facilitator is the illustrious Suzanne Luban. Suzanne recently retired from ten years of co teaching this clinic. First as the CDC’s clinical supervising attorney and later as its associate director.

She began her 35 years of criminal defense as an assistant federal public defender in the Eastern District of California in Sacramento. Three years later, she took her entire FPD caseload and started her solo law practice, where she primarily focused on complex federal trial, appellate, and habeas work for indigent folks.

In 2013, she joined me on the CDC. She has taught and mentored many of you who are present today, or many who will be watching this recording. She’s impacted every part of the clinic. Her genuine affection, concern, and connection with our students endures. On a more difficult note, I will say that following the murder of George Floyd, she served as a legal analyst for several news outlets.

She also served as a faculty editor for Georgetown Law Journal’s annual review of criminal procedure and taught in Stanford’s trial ad program and in CLE training courses around the country. As Suzanne often says, her decade at the CDC was the most fulfilling work of her career. And with that I’m going to hopefully do a good job of changing the view here to a medium shot.

And Suzanne, you can remain over there because that’s where you’ll see the medium shot best, I think. Let’s see, yes, you should, I’ll take my things. You can do the intro. May you use If

Okay, so do I have to stay here? As everyone knows, I’m very obedient.

Alright, thank you. Those of you who came, those of you who came last night, and those of you who are not here, I’m very disappointed. But, send my love out to all of you guys who will be watching this. Alright, my first Panelist is Carlie Ware Horn. She is the lecturer and clinical supervising attorney for the Stanford Law School Criminal Defense Clinic.

Before joining, way before joining CDC, she worked in civil impact litigation bringing racial justice and criminal law reform cases as the Relman Civil Rights fellow at Relman and Colfax, and as an ACLU attorney. I think if I can keep my head right there, it’s best. Carlie then served 14 years as a deputy public defender in Santa Clara County and in addition to many trials and a lot of important work that she did there, she founded and supervised the pre trial, pre arraignment, excuse me, representation review team, PAR.

She volunteers. Currently, still, as a high school mock trial coach, plays recreational women’s soccer, and is a proud mom of an 11 year old, a 9 year old, and a 4 year old. Carlie graduated from Berkeley Law and clerked for the Honorable Claudia Wilkin at the Northern District of California Federal Court. For three years before joining CDC, Carlie collaborated with many CDC students and alums and with me and Ron to bring to advocate for pre trial release of public defender clients. Although I was not involved in Carlie’s selection process to succeed me here, it was clear to me that Carlie was the most talented and inspired person to step into my shoes. Thank you for being here, Carlie.

All right, Carson White is a senior staff attorney down at the end there at Civil Rights Corps, currently, where she raises systemic challenges to the criminalization of poverty. She is currently challenging wealth based pre trial detention in California and North Carolina.

Before joining Civil Rights Core, Carson worked with the Santa Clara County Public Defender’s Office in San Jose with Carlie, where she co founded and co operated its novel early representation unit. In that role, Carson represented scores of presumptively innocent community members who were caged pre trial for no other reason than that they could not afford the scheduled bail.

And she raised successful challenges to the county’s pretrial detention schemes in California’s appellate courts. After law school, Carson was awarded a Stanford Postgraduate Public Interest Fellowship with the Habeas Corpus Resource Center in San Francisco, where she represented indigent, death sentenced Californians in their federal habeas proceedings.

Carson is a graduate of Stanford Law School and a valued alumna of the Criminal Defense Clinic. And Carson was among the first student advocates to argue for pre trial release under the then new Humphrey decision, working with Avi Singh, who you’ll hear from a little bit later and then later, of course, with Carlie. Carson lives in Texas with her partner Chris, their dog, and I think at least four chickens.

All right, Chessie Thatcher, our third panelist, is a senior staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union, the ACLU of Northern California, where she focuses on First Amendment issues, government transparency, criminal justice reforms and voting rights litigation. Prior to joining the ACLU, Chessie worked as an attorney at Kecker, Van Nest, and Peters, a San Francisco based law firm with a national caseload that focuses on high stakes litigation and trials. A 2011 SLS graduate, Chessie won the Deborah L. Rohde Public Interest Award and was a Levin Center Public Interest Fellow. She then clerked, she was not in the Criminal Defense Clinic, strangely. Thank you for having me today. It’s okay. She then clerked for the Honorable Sidney R. Thomas at the Court of Appeal for the Ninth Circuit, and the Honorable Robert Patterson at the District Court in the Southern District of New York. Chessie lives in the Bay Area with her husband, Eli Miller, who graduated from SLS in 2011 also, two daughters, and their dog, Whiskey.

All right. We are calling this panel, as Ron said, The Best Criminal Defense is a Good Offense, Collaborative Impact Litigation. It’s about two related concepts, collaborating in criminal defense and impact litigation in criminal defense.

I’d like to ask each panelist to please talk about your work on an example of impact litigation. Just tell us the story of your work on one of your impact cases. Carlie, can you start? Yes, thank you. It’s such a pleasure to be here today and to see everyone that’s here. Thank you for coming. And the story I want to tell is about a situation that I saw repeatedly when I was a public defender in Santa Clara County.

So to tell this story, I want you to imagine checking your mail. And we all know how exciting it is to go to the mailbox. Maybe you’ve got a postcard from someone that’s traveling. Maybe it’s just a bunch of bills. Maybe it’s a jury duty summons. But you go to your mailbox and you open an envelope that looks official and you open it and it says, Arrest Warrant. Okay, and it has your name, your date of birth, your height, your weight, your address printed on the top. And then there’s a dollar amount. It says $10, 000. And then on the back, there’s like these instructions, like, go to the police department with your ten thousand dollars that you obviously have lying around, right? And just give it to them, and they’ll hold it until your case is over. Or just go to jail, right? If you don’t have the ten thousand dollars, just go to jail. That’s what arrest warrants are.

And so, when I was a public defender in Santa Clara County, and focusing on early representation, I would get these phone calls from people with arrest warrants, and they knew they had an arrest warrant. They were trying to account for it, but they didn’t have money, right? They didn’t have the $10,000. And sometimes the arrest warrant could be for a non-violent offense, like they filed some kind of insurance claim that is being accused of being fraudulent or something like that. It’s not a danger to the community for any type of public safety reason and so these people would call me, and I heard myself on the phone telling them, I’m so sorry, like, if you don’t have $10, 000, I cannot do anything for you. There’s, like, there’s literally a line in the sand that the courts have drawn in Santa Clara County based on money. And I know, yes, I know, sir, that they didn’t even ask you if you have an ability to pay before a judge decided that $10,000 was the right amount for your case, but we can’t get you in front of a judge unless you go into the jail, get strip searched, housed, put on a bus, put in a cell, put on the little rubber flip flops and the black and white stripe outfit like you’re in the 1920s on the chain gang, and then come to court in that outfit, as an inmate, and then we can ask the judge to let you out again. That’s the process.

So I heard myself saying this to people and I was just like mortified that I was part of this system. And so I thankfully had enough time and training and knowledge to challenge it as a public defender. And so this is my story of, of basically a failed attempt at impact litigation.

So I filed something called a writ, a petition for writ of mandate. I didn’t really know how to do it, but I had done a couple before with more knowledgeable people like Avi Singh, who’s in the audience and we had collaborated on a few before, so I had like a template. Like I knew what it was supposed to look like, so I just kind of made mine look like that.

And I asked the judges in the trial level court that do the arraignments to open the court to people no matter how much money they had. Let me bring these clients in front of you, your honor, and you can decide in court whether they need to be jailed. Like, we don’t need to jail them first. Let’s treat them the same whether they have $10,000 or they don’t have $10,000.

That was the request. And I’m sorry to report to you. I lost miserably. I, when you file these petitions for this, it’s like a it’s kind of like, you know, when people go to the United States Supreme Court and they’re petitioning for certiorari, it’s like not mandatory that the court even hear it. You have to get them to want to intervene, and they did not want to intervene.

So I filed it in the in several different courts all the way up to the State of California Supreme Court, and basically I got what we call in the business a postcard denial. Back to the mail analogy. It’s like you get this, you’ve written this whole thing and all these stories of clients and all these constitutional claims and they give you this like, no thank you, not today.

And so basically I wasn’t able to change the policy, but I was really upset about it and I was really motivated. And along the way, because I talk so much, I’ve been talking to everyone I could think of about it and I caught the ear of the ACLU of Northern California. So after I lost I didn’t go away.

Is this the story of Carlie not giving up? Should we move on to Chessie? Okay, so Chessie, you’re obviously the best person to go next. I want to ask you to partly to address how the ACLU evaluates cases and causes to take on. Use this case as an example. And also mentioned CDC alum, Emi, and to just talk about how is it that such a, a local problem, really, I mean I don’t think this is being repeated in every county in California, and how the ACLU makes the decision to grant its, you know, auspices.

Well, she persisted Carlie did, and she reached out to Emi, who is a dear colleague, Emi Young and who also worked as a public defender after graduating from Stanford with my husband Eli. So, they’re Contra Costa public defenders, and Emi had just come to the ACLU and was really familiar with Contra Costa’s process.

That you had the protocol that Carlie was advocating for. Sorry, is this not recording? No, it just has to be right in front of you, I think. I just want to make sure it’s on. No one ever listens to me talk, so I’m not used to this. Definitely not my fault. Okay. So Emmie joined Emmie and Carlie spoke.

And Emmie was outraged that you would have to have this $10,000 or pay uniform bail schedule at the moment that you found out you had an unserved arrest warrant, or just pay and suffer, like, one to three days. We were finding, thanks to Avi and others, that people were spending three days in custody sometimes, and that’s enough time to have your car get towed, have caregivers that or not be given, because you might be a caregiver. It’s enough time to maybe not have your prescription medicines handy, and that was a real harm to people, individuals.

But the question is, how did that become an impact case in the sense of the ACLU taking it on? When we look at cases that come in the door there are, there are five teams. There’s the a criminal, there, justice team, there’s a democracy and civic engagement team that I’m a member of. There’s the technology and civil liberties group. And then there’s the racial and economic justice group and the gender and sexuality in the productive justice group. The matters come in the door via intakes, via partners, via just reading the newspaper and saying, like, that’s wrong. And then the groups sort of say, this issue falls into one of our buckets. And we analyze the issue in terms of what are the legal issues and who’s the community that is affected by this issue.

If we find that an issue touches on an important civil right or civil liberty in our group, then we might decide to take action. The way in which you could take action is to co get a coalition together, sometimes we write advocacy letters, but sometimes and often we decide to file a lawsuit. But filing a lawsuit is a major investment of time and resources, and we want to make sure that we do that right. And so when Carlie came to us with this issue, we, it was very clear what the civil rights issues and implications were here. It was a form of wealth based equal protection that claim that should be fought over. And the problem was not easy to identify in terms of what are all the different causes of action that we might bring.

So we thought through the claims, we thought through the venue. We’re suing a court. Do we sue in the court where we’re suing all the judges? Talking about their improper system? Like what’s the evidence of what other courts are going to be doing throughout this state and how do we get that evidence before the courts. We think about these legal issues, who’s the right plaintiff? If this is happening, do you want to stand up as an individual and say, I have an unserved arrest warrant, is that going to bring too much attention to you?

So we think about the, like the nitty gritty legal pieces, but also about what’s the impact of this case. So the impact of the case does, what community does it serve? Will we make some good precedent? Would we make some bad precedent? And that goes into the third factor of what is the issue that you, what is the risk that you could make bad precedent, that you could lose, that you could really botch this up.

When Carly came to us, we did the analysis that we do. We said to ourselves, this is an important civil rights issue. The population of people that we want to serve is very vulnerable and righteous to take on this case. The resources, probably we can do this with the Stanford Law School Clinic’s help, the CDC students, right on, you guys have already been amazing!

And we just needed to find the plaintiff. We looked for a plaintiff in Silicon Valley Debug, and an individual, very brave individual named Nicholas stepped up and he had found out that he wanted he wanted to join a job training program. And in order to do the job training program, he had to have a background check run. He was not, I don’t think he was employed at the moment and he was in danger of losing his housing. The job training program would have been a lifeline to that. But, he had an arrest warrant and served outstanding. And so he came and he called probably you, he called Silicon Valley Debug, and he got, and called Avi.

Avi, you’ve been so helpful. This is really the talk about Avi. And we didn’t have great answers, but we wanted to help him. And so Nicholas was very brave, he put his story into the pleadings, he verified the petition. And so this is what happened. It was very dramatic because he went to go live with his family after he was eventually kicked out of his house. And his family turned him in to the authorities. And he was booked for about three days. Up to three days. It was a really disorienting, traumatic experience for him. And eventually he got his day in court. At arraignment he was released without any bail conditions, it was on his own recognizance.

So you get a sense for, like, the trauma that Nicholas went through. And so his story is featured in our petition. We are worried about bad precedent. But I don’t think that in this case is that problematic. Because what you would have is this, if we did lose, and we don’t think we will because of developments that are taking place as we speak.

And I’m proud to say that on Monday, the first day of, will be the first day of a new protocol. And the new protocol will be exactly what Carlie had advocated for all along, so she was right. Unfortunately when we called the clerk’s office last week, they did not know about the new protocol nor does the website reflect anything about the new protocol.

So well, the fight goes on. But anyway, that is like a schematic of how the ACLU looks at a case when it comes in the door. When we think about who’s this case for, what’s the impact? What are the risks and resources that we’d be facing if we commit to this case? And so far, so good. Especially when we wrote a demand letter prior to filing our lawsuit that said, Please change this one more time. Here’s your shot. And they, like, essentially said F U in, like, more than the postcard, but on paper. Yeah, it was a whole letter. Yeah, it was a letter. And now what happens is hopefully we’ll be able to get some attorney’s fees from that. So that’s the pain point of government when they don’t listen to us.

Thank you, Chessie. All right, Carson, keeping with the bail theme. Please talk about your work on Humphrey related bail matters and in particular, the impact case that’s currently pending before the California Supreme Court. Sure. Thank you. I’m so excited to get to talk about this in a room full of law nerds.

This is rare. It’s very exciting. So I am, yeah, Civil Rights Corps. I head up along with Catherine Hubbard, another CDC alum. Our California Writs Project. And that is basically that instead of filing sort of a systemic, big class action or civil lawsuits that like Chessie was describing, we talk to public defenders, work with public defenders, see what issues they’re seeing on the ground, what tools they wish they had in their toolbox, like what’s a case you wish you could cite but that doesn’t exist yet and then work with them to strategically file habeas petitions in individual cases where people are being detained pretrial, like under those conditions that they want to challenge. Which is, it’s, it’s a really exciting model for a lot of reasons. In part because it’s, it’s very fast, it’s very flexible. And it allows us to center the stories of directly impacted people in a way that can be really powerful in front of like individual judges who are getting all of a sudden in a couple weeks like 20 petitions all on the exact same issue.

And it was, that strategy was born out of a case called In re Humphrey. Which was done in partnership with the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office. And I guess I should, this is the legal nerd part of the talk, I guess. But before Humphrey, the way that bail was set money bail, so the amount of money that you have to pay in order to be released from jail pre trial in California and still today, like most places across the country, is that there was something called a bail schedule, which is, it’s basically a menu. And on one side of the menu is all the different penal code sections, all the different things you can get arrested for, and on the other side of the menu is a dollar amount. And the court would say, okay, you’re charged with these three things, the dollar amount is X, Y, Z, back of the envelope math, adding them all together, you have to pay $100,000 to get out of jail, right?

And like, that was just it. That was the entire bail hearing. That was, you know, your most fundamental right to, to be free before conviction depended only on whether or not you had that amount of money. and we filed a series of cases raising like Cheessie mentioned, this equal protection due process hybrid challenge, saying that that was illegal. That if somebody was going to be kept in custody pre trial, it could only be because a court was making a decision that it was absolutely necessary for them to be kept in custody pre trial. That nothing else, short of their actually being in a cage, could prevent them from fleeing or from hurting somebody while they were out of custody.

And that, as part of that process, Before requiring money bail in any amount, a court had to inquire into somebody’s individual ability to pay to see if the money that they were thinking about setting was going to make them stay in a cage or not. Is everybody still with me? Okay, great. So that’s, that’s In re Humphrey.

We won that case, so that is now the rule in California. And afterward, we went around to public defender’s offices across the state saying how, how is this working for you? Like, what are you seeing now? What’s what’s keeping people in jail, like what should we tackle next? And the thing we heard over and over and over again was that people who were accused of misdemeanors and nonviolent offenses were still being held in jail, and were still being held in jail on unaffordable money bail.

And the reason that that was, I mean there’s a myriad of reasons that that was happening, but one reason was that there was a, like a second claim in Humphrey about a provision of the California State Constitution. It’s called the Right to Bail Clause. And these provisions, these provisions actually exist in like most state constitutions across the state and they are just universally ignored.

But it, it says that if you are not charged with a capital crime or like a very serious violent offense, a sexual assault felony or a felony where you’ve threatened somebody else with violence and if there’s not like really good evidence that you’re guilty and there’s not really good evidence that you’re going to hurt somebody if you’re out of custody. That you have to be let go pre trial. You are not eligible for pre trial detention.

And the Attorney General and Humphrey sort of like seeing the writing on the wall, right, that courts forever had been ignoring this provision just by setting unaffordable money bail for anybody and not worrying about whether or not they’re going to get out of custody, was like, oh my gosh, wait a minute. If all of a sudden we’re acknowledging that that unaffordable money bail amount is keeping somebody in custody, And people are only allowed to be kept in custody in a handful of, you know, the most serious cases. Like, these people are not going to be in custody anymore. And that’s just like a massive tool gone, right? To coerce guilty pleas from people who are charged with these low level nonviolent offenses.

And so the Attorney General came up with this pretty disingenuous argument, which was that the, that provision of the California Constitution had been silently repealed by California voters who passed a provision that had not mentioned the right to bail, altering the right to bail or increasing the state’s authority to detain people pretrial at all. And the court in Humphrey said, you know what, like, we actually, like, are not gonna touch this right now. That feels very messy. That feels like not necessary in this case. We’re just gonna let it go. And courts across the state in the wake of Humphrey had, like, taken that and run with it. And said, you know, we don’t have to worry about it. We’re gonna keep detaining these people because we have increased authority to detain people in any case we want to, regardless of whether or not they’re dangerous.

And so we, we went back at it. We worked with public defender’s offices across the state, including Avi Singh at the Santa Clara Public Defender’s Office. and that resulted in a case called In re Kowalczyk being filed. And Mr. Kowalczyk was a, a 50 some odd years old unhoused disabled man who found several credit cards that people had lost in San Mateo gas stations, just like leaving them behind at the pump.

And after having them just in his possession for months, he walked into a Five Guys in San Mateo, ordered a cheeseburger, and started swiping credit cards to try and pay for it. Eventually, one of the credit cards worked, paid for his cheeseburger, and he immediately had a change of heart, threw the cards away, told the manager he had changed his mind, didn’t want the cheeseburger, and walked out without taking it.

The San Mateo District Attorney charged him with three felony counts of identity theft. One for each time he had swiped a credit card along with, you know, possession of someone else’s identifying information and a series of misdemeanors. Mr. Kowalczyk was arrested, brought into court. The judge doing the pre Humphrey thing set bail at 75,000. Humphrey came down in the interim. He brought a motion saying, Hey, wait a minute. This isn’t how this is supposed to work anymore. You need to let me go. And the judge said, Okay, I’m going to detain you without bail at all. That means there’s no amount of money you can pay, nothing you can do to get out of custody.

Mr. Kowalczyk ended up staying in custody for six months, before, during which time he lost out on housing opportunities that he was eligible for in the interim because he wasn’t able to make his meetings with the housing people. And was denied surgery to remove a, a, like, a long awaited surgery, like, for years that he had been on the wait list to have a cyst removed from his jawline that rendered him deaf in one ear. After six months in custody, the district attorney offered him a plea deal. He could plead to one of the tiny misdemeanors they had charged him with at the beginning and get out of custody that day which he did. And it was the statutory maximum amount of time he could have spent in jail for that misdemeanor.

Mr. Kowalczyk’s case is now in front of the California Supreme Court where we were counsel in the Court of Appeal and won on the Section 12 issue. But the Court of Appeal did something again, I think very disingenuous and said that although this constitutional provision does control when somebody can be detained pretrial in California, courts can just get around that if they intentionally set bail in an amount that they know somebody can’t afford.

So, if if the court in Mr. Kowalczyk’s case had just said, I’m actually going to leave it at 75, 000 bail, under the court of appeal opinion, that would be fine. So we’re now amicus, along with the ACLU NorCal in the California Supreme Court, and the briefing just wrapped up like this week, finally.

And it’s, it’s a really exciting time if we win, and I, I think we will win. It has the opportunity to be, I think, maybe the most liberatory decision in history. It’s, it’s hundreds of thousands of people a year who are now in jail in California on these low level nonviolent offenses who just wouldn’t be eligible to be in jail anymore. Yeah, thank you for listening.

Wow. So I’m just going to ask you, Carson, to just amplify one aspect of that. So these public defender organizations could have filed their own writs. You could have just sent a postcard saying to people, call through your cases and go ahead and file writs. But instead, Civil Rights Corps, just like the ACLU in, in Carlie’s case, took on and gave your power, I guess, to that lawsuit. So I wanted to just ask you, what does it look like and why is it so important for organizations like Civil Rights Core to partner with public defenders in impact litigation?

Yeah great question. So we partner with public defenders in all of our, in all of our bail work including like our more traditional sort of bread and butter like 1983 class action lawsuits and that’s, I mean there’s so many reasons for that, like one, public defenders are on the ground, they have an incredible amount of insight into what’s happening in courtrooms and what is going to be the most useful rule changes, right logistically it’s also pretty important, like public defenders have access to the directly impacted people, their clients who are going to be plaintiffs and, you know, who are going to be the subject of these habeas petitions. So, like, you, you need to be working hand in hand with them to be able to bring these cases.

But I, I think most importantly, like, the truth is that the, you know, the Humphrey violation I described where judges are just, like, looking at a menu of prices and jailing people based on that, like, you could throw a dart at a map anywhere in the country and hit a county where that’s happening.You can walk into any courtroom in the country right now, including places where it’s supposed to be illegal. And, like, that is how bail is being set. And we have learned to really only bring these cases in counties with robust and passionate defense bars because without them, these legal rulings are just words on a paper, right?

Like, you need to have people who are in the courtrooms every day making these arguments and forcing these rulings for them to mean anything at all. And for the same reason, we really try and prioritize bringing cases, places with robust court watch programs, right? So members of the community who are just showing up in court every day, telling stories about what’s happening there, watching the public defenders you know, in order to hold the public defenders accountable, right? If they’re not making those arguments, why not? If judges aren’t listening to them, who are they? Why not? So those are, I mean, just as important as, as any other, like, legal fact that’s gonna go into a, a good case.

Thank you, Carson. All right, Chessie, you’re next. So you mentioned that your plaintiff, his family turned him in and he spent time in jail and lost these opportunities. So in the criminal defense clinic, we always talk about client centered work in all the clinics. So is impact litigation client centered and how do you balance the client’s needs and wants with the greater purpose behind the impact litigation?

It’s a great question. And to answer that question, but also pick up on what Carson was saying I do think that public defenders are the substantive experts in terms of some criminal justice reforms. And the goals, the bigger goals for the impact are change in public discourse, what large numbers of people might be covered by a ruling, and what institutional reforms you can hope to achieve. So those are all really lofty, and then you have an individual who’s suffering because they, like Nicholas, didn’t have a lot of resources and got picked up for a non violent offense and weren’t really posing a risk to the community at all.

So, one of the first things that a person who takes on one of these bigger cases that’s about the civil rights component, when there’s a live criminal case going. You have to say like, am I going to put you in jeopardy? What’s the harm to you? What’s the harm reduction that I could offer you if we take this on? And then to be really honest, like, this isn’t, often times our cases look for injunctive relief, so they’re not looking for damages. But people love to think of like, Oh, we’re going to sue and I’m going to get money. And that’s not actually very easy to do. There are better places than the ACLU if you’re a client who needs to get some money than to come to us, don’t do it. Because we’re really looking at more of the bigger impact change and not damages. But that’s something we have to be very clear with our individual clients.

And then if you have multiple clients, and I’m sure you’ve all learned in ethics balancing their interests against each other, or is there going to be a time when one client wants to get off the case if there’s an exit ramp for that person but it doesn’t address the other persons needs and so we need to keep going in the case. And so, I think it’s very important in cases that are client centered.

Some of them aren’t. Some of them are just like big constitutional questions, and you have a taxpayer claim by an organization. And that is client centered to something, but not to the individual as much. The individual cases, it takes a lot of ground work up front to talk about what the case can and cannot do. And to think about, maybe this isn’t best for you. We would love to have you be a part of this case. But especially in immigration cases where there are so many injustices it’s a very risky proposition.

I want to just take a moment to ask for a time check.

Okay, so there’s one more question I definitely want to ask you, Carlie. You sued your very own judges before you left the Public Defender’s Office. So I’d like you to just talk briefly about what dangers do public defenders face in challenging court practices where they’re repeat players before those same decision makers?

Yeah. There’s so many ways for me to answer this question I think the most honest, real beginning of the answer is my dad’s a judge, so I grew up with a healthy sense of rebellion against people who think I need to follow, like, curfew and rules and, like, you know, it’s just like, why, excuse me? I just, that comes very naturally to me from my upbringing, so I don’t know if that’s just, like, unique to me I all, but, like in all seriousness, I really think that when many lawyers, no matter what their profession and many non lawyers you know, there, there are times in our decision about where to put our resources and our lives that we decide to stand up, you know, and sometimes we put ourselves in physical harm’s way or in, you know, political jeopardy or it’s uncomfortable. And that’s just the commitment we’ve made with, you know, how we’ve decided to live our lives.

So, to me, it wasn’t actually a very, very big risk to challenge, What I see as an unlawful practice, like the big risk is someone going to jail and losing their housing and their vehicle and their, you know, their children changing custody. It’s uncomfortable to, I mean, literally the last conversation I had with the judge who’s named as one of the defendants, I was like asking him for a letter of recommendation. I was like, you know, your honor, like it’s been, he knows my work. I’ve done trials in front of him. He knows me really well. And I just, you know, I, I asked him to be a reference for me and he said yes, and then the next time he hears from me It’s like being served with a complaint But he knows me so it’s like I imagine him getting it and like smiling, you know and being like, yeah, that’s right. She’s such a pain in the butt, you know what I mean?

And I’ll get rid of her cause she’ll get a different job. Right, yeah But I, I really take it seriously, you know, I’m reflecting a lot because my mom is here in the audience today. And I, you know, she’s actually an alum of Stanford Law School. My parents met at this law school and graduated in 1972. And I think about what it would have been like for them to attend this institution. You know, as a woman in the late 60s and as a Black man during that time, it’s not like there’s a lot of you in law school. And so, you know, that discomfort that they experience in, you know, putting themselves out there to get that education and to improve their lives you know, a rising tide lifts all boats.

So, as hard as it was for them to come here and get that education and be one of the only people in the room and be the voice, you know, that everyone’s looking to, like, it’s not, it’s easier for me to sue a judge now because I have that power and that comfort and challenging authority. And so I appreciate, you know, we stand on the shoulders of those who come before us.

And the last thing I’ll say is, one of the reasons I was comfortable to like put my name on something that’s challenging these people in authority is because I always treat them as human beings with respect, dignity, politeness. Like I will go to a judge and ask them for something that I know they’re going to say no to and sometimes I ask them because I know they’ll say no and I want them to have the chance to look me in the eye. I mean, I’ve had judges where I say. Judge it’s so nice to see you today. Just wanted to let you know, I filed a complaint against you for the way you treated me in court. I thought it was racist and sexist, and I wanted you to hear that from me because I take this community really seriously and I want us to improve. And so I, I, but I didn’t want you to hear it as a rumor. I wanted you to hear it from me. And I looked this gentleman in the eyes and said that to like an older, very well respected judge, because I, you know, I want our community to be better.

So it means a lot to me to be able to actually, I think it’s like an honor to sue the judges that you appear up in front of every day because how else are they going to get better? It’s like, why do you have a personal trainer? You know what I mean? They yell at you and you get better. It’s like, I’m the judge’s personal constitutional trainer.

All right, I want everyone to take that back with you to your practices and be a trainer for some judge. So I think it would be great to ask for questions. And I want to, so people have questions about what these amazing advocates have talked about. And, or if you yourself are doing impact litigation, and one person here in particular I know is actually doing that Michelle, but please raise your hand, stand up, and maybe, okay, we’re gonna, Daniela’s gonna bring you a microphone, and just give us a, a little thumbnail on what you’re doing, or what your question is.

Nick! Thank you!

Hey everyone, I’m Nick Eckenweiler, class of 2020. I did the clinic in the fall of 2018. And I remember Carlie and Carson from down in the office in San Jose. Currently I live in Oakland and I work for a very small impact litigation shop doing housing and land use litigation. Basically suing cities across California to make them build more multifamily and affordable housing.

Interestingly, the posture of these cases is petitions for a writ of mandate. Although these are not discretionary, these actually get heard, whether the judges want them to or not. and one of the cases we have right now is against Santa Clara County for a zoning decision they made in Professorville that we think they’re not allowed to make under state law, which is pretty exciting. Waiting for the Superior Court judge to actually write an opinion on that. And we’ve also got another very exciting case going on in a suburb of Los Angeles, La Cañada Flint Ridge, which because they haven’t updated their housing plan to accommodate housing for low income people because they have certain ideas around what kind of housing should be in their city and what kind of people should live there their zoning code was suspended and a project was submitted with an affordable housing component that we think they were obliged to approve that they have not approved and we are asking the court to mandate its approval consistent with a relatively untested provision in state law. So, that’s all very exciting.

Thank you. Anybody else? Other people? I know there’s going to be more people who have questions or comments to add. Can I call one person? Carly Bittman? Please do. Yes. So, I want to talk about Carly’s work and talk about public defenders again in the context of the best defenses is an offense.

We had a case, the ACLU had a case that involves the right to travel, which is, I think, one of the most important constitutional rights that’s not explicitly in the Constitution. So Carly had gotten, with others, a a tip that the public defenders were seeing their clients who were repeatedly arrested in the Tenderloin for drug sales.

They were being sued by the San Francisco City Attorney. In a civil capacity, so that they would get lifetime, permanent, no exception, except for appearing in court, stay away orders, exclusion orders, keeping people from 50 square blocks in the middle of the city. And it was a, we can, I think if you are familiar with the Tenderloin, we can agree that it’s an area that has a lot of challenges, but keeping people forever away from the center of the city and then having them be represented by themselves. And most of, many of our clients, I think all of our clients were primarily Spanish speakers. So sophistication with dealing with the court and a defense, they had no idea what was going on. They weren’t even served in many of the cases.

And Carly stepped in and did the most amazing job and argued in front of the California Court of Appeal. And secured a right to have these individuals move freely and get this matter, which really was a political fight about the city attorney and the current district attorney in San Francisco who gets to, like, I mean, it was, felt like a pissing match between grown up men.

Can we ask Carly to comment on that? Well, okay. Good.

And say who, where you work. Hi everyone, my name is Carly Bittman. Car, Carly Bittman. I graduated Stanford Law School in 2015. CDC alum from 2014 is when I did, or 2015. I forget when, which year it was. 2015, thank you. Vina and I were partners in the clinic. And I currently work at a firm called Swanson and McNamara, which is a trial boutique in San Francisco that does, primarily federal criminal defense, but we do a little bit of everything, and the only thing I’ll, I’ll add is it was a great experience to work so closely with the ACLU.

Chessie put that all in terms of what I did, but it was what we did. And I was really grateful to, to work with Chessie, who’s an incredible lawyer. And we worked really closely with the San Francisco Public Defender’s office there too, and learned a lot from them and what they were seeing because these were public defender clients who were now being sued civilly.

And part of the reason why our firm was asked to, to help is that we do both criminal and civil work. And so we thought we’d be a good fit in defending these civil cases, even though it was really all about alleged drug sales. And, and we were successful at the end of the day after getting a good we won in the trial court, went up to the Court of Appeal, Chessie and I split the argument and got a good ruling there.

And then the cases got dismissed by the City Attorney’s Office at the end of the day. So it was a success and it, again, great experience, and I’m,. So glad I met you, Chessie. Mutual. We’ll have our little love fest moment in front of you all.

Thank you, Carly. Others? Katherine. Your own, if there are questions, or your own impact work?

Hi, I’m Katherine. I am an alum from 2014, and I was in the first clinic with Ron and Suzanne, which is great. So my question comes from my experience practicing law. So, after I graduated, I, I did some impact litigation at the ACLU of Northern California. And then after that, I did direct services work as an eviction defense lawyer.

And so, this is kind of implied in a lot of what y’all have been talking about, but I felt as a student at Stanford that there was a sense of, here are the students who are going to do direct services, and here are the students who are going to do impacts lit. And you’re kind of siloed off like that.

But when I went off and practiced. I found that as, at the ACLU, I was a better attorney having worked with Ron and done direct services. And then as an eviction defense attorney, I was certainly better having done years at the ACLU of impacts litigation. And so, I have two questions. The first being, What do you think Stanford can do better about having more of an encouraging environment to tell students that they can do both and that actually serves you both?

My second question is, I think choosing one or the other is oftentimes a question of temperament, of your personality, what suits you more and what will make you happier and more fulfilled as a lawyer. But I also think at institutions like Stanford, there’s sometimes explicit pressure to do impact litigation.

There’s this idea that it’s better, it’s more prestigious, it’s why you went to Stanford. And I think that’s such a shame for students because my work, at least doing direct services, I think made me such a better attorney and, and so too at the ACLU. And so my second question is, what do you think Stanford can do to change that sort of implied pressure of going one place or the other?

Just because personally, I found that it made me a better attorney to have done both.

So thank you for those questions, Katherine. I kind of want to shoot this over to Carson because I, as anyone who was my student has heard me say, direct services is impact work, and since you’ve done both, can you address that? And you came from Stanford.

Yeah, oh gosh, this is such a good question. I have so many thoughts. I’m trying to think about what I can say on a recorded line. Hi! I guess just to, to answer Suzanne’s question first, like, I, I really don’t think, I, there’s, the two are so intertwined and like something that, you know, working with Carlie that we saw every day is like, we were doing direct services and we were doing hyper localized but like it, everything we were doing was impact work, right, just showing up in court every day making these arguments for the first time and I should say, like, that is also true of the pre trial justice program that the criminal defense clinic and Avi, when he was, head of research at Santa Clara, pioneered where students came and represented people in their arraignments, you know, so, but just making these, these arguments over and over in front of the judges who were the decision makers every day changed the way that they approached these decisions, and like I’ll never, I, you know, we’ve like, I don’t want to say I’ve had like so many legal victories, because that’s not true, but, but like one of the, the proudest moments, I, do you remember it?

Carly the day Judge Hawk came into a bail hearing and he had a a notepad and he sat down and It was like the entire feeling in the room shifted It’s like something is new here and he was like, I don’t want to hear from either of you He was like, I have some questions and he was like, are you saying that money bail is necessary, like, to the district attorney, and the district attorney was like, what are you, he was like, are you saying that the person needs to be detained, and if so, why? And it was like, oh my god, he read the case. Like, I was like, go with him. Where it became, it was like, we had been making these, and something had sunk in.

And, yeah, so I guess it’s just, let’s just say, you know, direct services work is impacts litigation work. You showing up and being in that position every day in front of the same decision makers has the opportunity to change how a practice happens, and maybe it’s. Maybe it’s just in that one courthouse, right, but like, that’s thousands of people whose lives are being touched by your work and the changes that you’re making.

I totally agree with your read on this, Katherine, like, that was completely my experience coming through Stanford. There’s, the reality is that there’s this idea that impact litigation is more prestigious, and frankly, there was this narrative at the time that I, I hope has maybe changed, but that if you were going to go into trial criminal work, you needed to go be an AUSA.

That that was the fanciest job you could have, that that is, you know, that’s like the most good you could do because you have the most power in the system because you can decide who’s charged with a crime and who’s not, And that was really messed up. It was very messed up. And there just weren’t a lot of resources for people who wanted to be public defenders.

Going and being a, just a county level public defender, not even in the federal system, was, it was basically unheard of. And it was like. Relying on Ron and Suzanne, frankly, to be the institutional knowledge about how to do that. And so I think, yeah, I think investment in relationships with, with county level public defender’s offices at an institutional level is invaluable.

I think more information for students about what the process is for how to do that yeah, would, would be massive. And, and changing this idea that the power.

I’ll just say it. Changing this idea that our, our goal as lawyers is to gain as much power as we can in this, this really broken system as opposed to relating as closely as we can with the people who are impacted by it and working to build their power in whatever way we can, which is a, it’s a total narrative shift for how institutions like Stanford work.

Yeah, alright. And, and you are all, at least the people who were our students, are the choir for that, right? Nida, did you have a question?

I was just gonna add to that the narrative shift that goes into that is also state versus federal. And federal work is great, but it’s like 1 percent of criminal cases. And meanwhile, we’re in a law school in, you know, one of the states with the largest prison populations in the United States. So. That was another one that took me a few years, like, just because the federal system is prestigious doesn’t mean it’s where you can even make the largest impact.

And I was just going to make a point as well. A couple years ago, I worked with John Butler, another CDC alum. I was at a law firm in Big Law, and I was bored, and I wanted to leave. And I reached out to him, and I was like, is there anything that I can help with? And I ended up helping on an safe injection site impact litigation case in Philly. And so that’s just another for the younger alums who maybe are at law firms now. Often law firms do have pretty good, like, pro bono programs. So reach out to other people from CDC and just be like, Is there anything I can help with? I will write an amicus brief. I will do whatever. And, and it’s a cool play, way to get involved in some of these issues.

Can I just add to the answer to Katherine’s question as well? I, I’ve, I, it took me, I feel like a long learning curve to differentiate between being elite and being elitist, and I feel like you can be an elite anything, impact litigation, direct services, but it’s seen the elitist frame views only certain things as like the, you know, boutique, primary, fancy, golden ticket things and so I feel like my life actually improved so much when I realized I could be the best public defender imaginable and just operate on that channel in the best way I could and not try to like, win the contest of, like, getting to, you know, become the, like, civil division of the chief justice of the whatever leader of the world. Do you know what I mean? It’s like, that’s cool. I’m just going to go help people that are in jail. And to, like, do that so excellently. It was just much more satisfying.

Yeah, my husband Eli had this same kind of struggle. He graduated from here with this IP interest, intellectual property interest, as well as wanting to do criminal defense work. And he had a job offer at Munger Tolls, which is a wonderful law firm in the city. And he had a job offer at the Contra Costa Public Defender’s office. And his heart wanted to go to COCO.

But he felt this, like, pressure. And eventually, he didn’t go to Munger. But he had the offer open, and every New Year’s, I remember him, like, sitting there thinking, like, What am I going to say? My dad was a district attorney and he, my, my family kept saying, do you think one day you’ll be promoted if you become a public defender to a district attorney? And it’s like a fundamentally different understanding of the law.

And but Eli’s so happy. I mean, being a public defender is hard. It’s legit work and it would be way more interesting to do it as a state person than a federal person because the sentencing guidelines in federal court are so. It’s hard and messed up that no one goes to trial and it’s really a grim situation.

We used to say we felt like a potted plant in some of the mandatory minimum cases if the client wanted to file a bail motion, they were going to file the prior. Yeah. Anyway Ron, are we, do we have time for Vina or?

Parliamentary.

No, just on the, on the point around federal, since I was a federal defender, you were a federal defender, there are federal defenders in the audience. Fortunately, federal defenders do go to trial and in fact, right now, we’re in the middle of a period where there are a ton of trials in this district. In fact, I was sharing this huge victory that I’m not gonna talk about but that happened in the Northern District like a three week trial, I think, was it, Carmen?

Amazing results. So, in, and the Federal sentencing guidelines are no longer mandatory. And so that also, part of the battle is helping judges understand just how much discretion they have. But it really is, it’s a new morning in America in the federal system. Okay. That’s it.

Hi everybody. So, I’m not a Stanford alumna. I’m not sure if I’m allowed to even offer my thoughts. But along the themes that we have discussed, I think that I re, what really resonated to me, with me was Suzanne’s observation about direct representation, direct services being in impact litigation And as an appellate attorney, appellate work is an excellent example of that principle.

I mean, all of us here have enough experience and understanding of how our system of court to review work. And once you take a case on appeal, if that case involves a legal issue, that legal issue once decided is going to have to be binding authority in your jurisdiction. So direct representation leads to decisions that have impact, broad impact in the federal system.

That means impacting all nine or 10 states that comprise the Ninth Circuit. So, it is actually the biggest circuit in the country. It is a huge, huge impact and a recent example of that kind of work is is about the kind of level, the level of suspicion that police must have about somebody’s parolee status before conducting a parole search.

You think of that as a state issue, a California state issue, but our clients, federal defendants, frequently get charged pursuant to these parole searches. My office, unfortunately, has been at the losing end of that issue, partly because a California Court of Appeal had already decided that issue in a negative way.

But we are taking, or we’re hoping to take that case on a before the en banc court. And to that end, the ACLU actually filed an amicus brief in support of our petition. And so did the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, the NACDL. So that’s another example of the kind of impact litigation that derives directly from direct presentation, and I will say also this as public defenders, we don’t have the luxury of choosing our clients. We also have the luxury of not worrying about the next person because our ethical duties compel us to only consider the, the interests, of this particular client at this particular moment. So that might have occasionally unanticipated consequences, but from a professional perspective, it does liberate us to do always the right thing for this particular client. Thank you.

Thank you. So, Ron, do we have time for Vina? Okay. Thank you.

Now I feel I have to answer or ask the best question ever because there’s been so much anticipation. But first, introduce yourself and say where you work. Okay, my name is Vina Seelam. I am currently an Assistant Attorney General in the Northern Mariana Islands in the civil side of things. But previously I was a public defender for three and a half years in Alameda County and then three years in the Northern Mariana Islands.

My question is I think it’s geared towards Carlie mostly. As a younger public defender. I often felt like I noticed all of the issues, all of the bad things that were going on that I wish someone would come in and do a writ about or do some what we consider to be impact litigation more so. But I didn’t feel like I had the capacity to do anything about it.

I didn’t also feel like it was my role as the lower level misdemeanor attorney to challenge judges in that way. And I’m not so I think my question is at that level when you’re noticing all of these things, One: How do you pick what issue you’re gonna go for, Two: What do you do? I mean Do you go to a supervisor in your office and tell them and hope that they do something about it because as that younger attorney and then it, I imagine that you’ve been filing writs throughout your career, but how long did it really take you to get to that point in your career where you could pick this one issue and just tackle it with some authority?

That’s such a good question. I, this is probably the fifth effort that I did.And I am just, I don’t know how to scale this or like apply it broadly, but I just write the brief first and then I show it to a supervisor and say, I’d like to file this. Okay, you know, and I feel like if the claim is developed, if I put the work in and it’s like about, it’s ready to be stamped and filed, it’s a very different decision for someone in power to make to block me from just like shining a light on it than if I’m like, let’s workshop this idea and like, you know.

So there was a whole period of time where I was a misdemeanor lead. So I was like, had the job of You know, just like, supporting younger attorneys. I was in misdemeanor court, but I got really upset about the way that bench warrants were being issued without, I didn’t feel like the people who were getting the, bench warrant is like when you miss court and the judge will just be like, you missed court today, so $5,000 warrant. And they were, I felt that the judges were doing that when, like, I had a case where I was like, Your Honor, I just talked to my client on the phone. He’s not going to be here today. He’s still working on getting his driver’s license back because he owes, like, thousands of dollars in fees. Can I come back? Oh, bench warrant. I, I need him to be here. And so I decided to challenge that with a writ just the practice of issuing bench warrants without notice.

And what I did is, I was in the same boat. I was like in the misdemeanor team, we had so many cases, I was in court all the time. And so I just asked my family like, Is it okay if on, I think it was either Tuesdays or Thursdays, I don’t remember. There was just like one day where I just like did a double. Like I was just like on Tuesdays, I’m gonna work and be in court, and then I’m gonna like go to dinner with some colleagues, and then I’m gonna come back and work like another day. You know, and I’ll put in like another six to eight hours working on these writs, and it was, I did that, and I lost, and it was really demoralizing, and it didn’t work.

I mean, there were some, you know, whenever you make these efforts, there are impacts that sometimes you don’t, it’s not like you win the case and change all the policies, but like, You know, you, when you write a writ, you serve the judge. The judge is like the opposing party, and so I personally serve the judge.

I would go to the judge and be like, I wrote this, and I’d like you to know about it here. You know, and they’re just like, what is this? So now the judge knows that I’m watching. You know, or you call Silicon Valley Debug, like community organizers. Or you call the newspaper, you know, and you just say, hey, I’m litigating this. Please watch. Please come and like, you know, and then maybe you don’t win but the judge is like more polite to people or says, I, I’m, I could issue a warrant now but instead I’m gonna give you a stern warning and you’re just like, okay, I just won. You know what I mean? Like, I just won because I didn’t ask for permission from somebody in power who doesn’t benefit from, you know what I mean, making other people in power uncomfortable.

And I invested, I mean, but it’s a sacrifice. I had to miss dinner with my family and like putting the kids to bed and like on Tuesdays I didn’t see them. You know what I mean? But, I got to go to dinner with my colleagues, and like, I bonded with those misdemeanor lawyers because they’re doing a double anyway. Like, they, I would go home and they would come back and get ready for tomorrow. So it also gave me some credibility as a, you know, like a, like, leader in the office that I built trust with some of the people that are working so hard because we can’t keep doing this work without each other. You know? So part of that extra impact work is just like, showing up together.

Can I jump in? Yes. So, real quickly, I, so I had this experience recently, too, like, I, I had, when I came to the Santa Clara Public Defender’s Office, I had been out of law school less than a year and I was there on a fellowship, and so my job was just to, like, do bail hearings. Like, that was it. Like, I showed up my first day, and they gave me a list of 200 people in the office who needed a bail motion, and they were like, good luck. And so I had that moment, like, once a week, where I came in, the most crazy thing just happened, and everybody that I talked to was like, yeah, And I, That’s the, that’s what happens. And I … Meaning you lost . . . Yeah, meaning I lost in a banana’s way. You know, in particular, like the, the judge saying, well, I’m required to presume that this person is guilty at their bail hearing.

And I was just like, well, that can’t be the law. Like, there’s all sorts of reasons that can’t be the law. And everybody I talked to was like, yeah, that’s the law. That’s always what they’ve said for all of the decades. And what was so cool about that is that I then did the thing where I went to my supervisor And I was like, this is so crazy. And the supervisor was like, yeah, go, go give him hell. Like, go, because my supervisors were Avi and Carlie.

And you know, I think, like, looking, I don’t want to, like, be ageist, but I’m like looking around and I’m like, there’s a lot of us who, like, are now in these positions where we’re not first year misdemeanor attorneys anymore. And recognizing you know, something that, like, Carlie told me often is that, you know, to be really confident in those, um, gut feelings, because there’s a, a perspective that somebody new to the system has where they haven’t been colored by seeing this thing happen over and over again and being normalized. And I was so lucky to be working with people who really valued that. And I guess I, I just want everybody in the room to, you know, myself included, I’m a, what, a fifth, a sixth year attorney. You’re old now. I’m old. I’m an, I’m an adult person. Yeah, to, to value that freshness because it’s, it’s, it’s really powerful.

I think the way that a person, a mentor said, insecurity is actually like your best friend. Like, if you feel like you’re not getting it right or it doesn’t make sense Do something with that feeling. It’s tiring, though, to your point. I mean, Carlie talked about how she had to miss dinner time and bedtime, and query whether that’s like the worst fate in the world, if you have a four year old.

Yeah, it’s like, I have to work late tonight, and tomorrow. But seriously, it does take a toll. So, hopefully you also reach out to, you said the newspaper, court watchers, ACLU, Civil Rights Corps. Like, we want to have your backs, too.

All right, so I think that we’re probably going to wrap it up and just I want to say give him hell.

Okay, thank you again. First of all to Suzanne Luban, Associate Director Emerita of the Clinic, to to, to Carlie Ware horn, our clinical supervising attorney and lecturer in law. To Chessie Thatcher, senior staff attorney in the Democracy and Civic Engagement Program at the ACLU of Northern California also SLS alum.

And to Carson White, SLS 18 criminal defense clinic alum, senior staff attorney at Civil Rights Core. And to all of you, I’ve really enjoyed our opportunity to have this conversation together. So thank you panelists.

Panel 2: Movement Lawyering: Centering Impacted Communities