Essay: Lessons Learned from Grassroots Advocacy for Local Police Reform

Essay: Lessons Learned from Grassroots Advocacy for Local Police Reform

Michele Wittig is convener of the Santa Monica Coalition for Police Reform. In this personal and historical essay, the longtime Santa Monica resident considers how grassroots advocacy might work concurrently with local governmental civilian oversight of law enforcement to enact structural reform.

Why is local police reform so challenging—even though police chiefs in “progressive” cities like Santa Monica have expressed their support for it?

One way to think about police reform is to compare it with long-running software that meets the needs it was originally designed for but doesn’t allow for structural improvement. Programmers call it “legacy software.” Legacy policing is like that. It was installed in our civic operating system generations ago. It performs many functions well, but those who are advantaged by it typically are less aware of the ways they benefit—and, if aware, they are less motivated to change the system.

Legacy policing also produces disparate impacts, regardless of good intentions and efforts. In the minds of many, reforms like diversity hiring and community policing are sufficient to meet modern needs. Any remaining disparities in outcomes are not due to policing. Others view such improvements as updates to an outmoded system whose code needs to be rewritten.

Deference to legacy policing helps explain why reform efforts in Santa Monica have been like putting patches to an old computer program. It helps account for why some of the city’s public safety commissioners believe that addressing racial disparities in policing is not within a civilian-led commission’s purview. And it’s a reason why some SMPD officers think that the presence of racial and ethnic minority officers in their ranks means that bias in policing is not a local problem.

Does Santa Monica have the political will to examine its police department’s legacy operating system and enact structural reforms? It’s my hope that the city will build on what has been accomplished and move a robust reform agenda forward.

Early History of Police Reform in Santa Monica

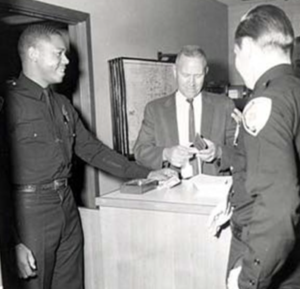

The local effort to reform policing dates at least to the 1960s after Mr. Nat Trives, a Black resident, was hired by SMPD. Officer Trives soon learned that Black officers were assigned only to Black neighborhoods so that white Santa Monica residents would be spared the humiliation of being issued a ticket or arrested by a Black officer. He was the first Black officer to write a ticket to a white citizen.

When Sergeant Trives applied for promotion to lieutenant, he was turned down. That’s when he decided to quit the force and make change from a position of leadership outside the department. He launched a career as a professor of criminal justice and ran successfully for Santa Monica City Council. He eventually served as Mayor in the 1970s.

In 1986, the City Council authorized an independent review of SMPD. In a kind of poetic justice, Mr. Trives and a colleague were given the contract. Their 1987 report documented weaknesses in SMPD personnel practices and tolerance for racist and sexist comments directed by some officers toward others. In response, the city implemented reforms which resulted in the hiring and promotion of more women and racial minority officers.

My involvement in local policing reform had its beginnings in January 1987 when I joined the local branch of the NAACP after hearing Mr. Trives speak at a Martin Luther King Day celebration. In the years that followed, I drafted two petitions for police reform. The first was launched in 1993, at a Speak Out for Justice on the steps of the local courthouse.

The branch president announced an initiative to establish “a citizen review board of the Santa Monica police.” But the effort was quietly dropped soon thereafter because the African American police chief came to one of our NAACP meetings and made the case that oversight would undermine his leadership. The second petition, also unsuccessful, was circulated in 2014 during the administration of a subsequent chief.

Launch of The Coalition for Police Reform

In 2015, several highly publicized incidents of overaggressive policing toward people of color in Santa Monica occurred. The highest profile of these involved Justin Palmer, an African American father of four who was attempting to charge his car at a free 24-hour electric vehicle charging station. Although the city attorney dropped the charges, Palmer filed a civil rights violation claim. A federal jury unanimously found an SMPD officer liable, and the plaintiff was awarded over $1 million for his injuries and loss of future employment.

That same year—while on a ridealong in a police car at the conclusion of my participation in the nine-week spring session of SMPD’s Citizen’s Police Academy—I heard an officer use a racial slur when he asked a colleague in the vehicle to run a background check on the Black male driver of a Rolls Royce. In August, I convened about a dozen activists who agreed to meet weekly at a local church. We discussed social science research on bias, examined relevant sections of the SMPD Policy Manual, reviewed President Obama’s Task Force Report on 21st Century Policing, and acquainted ourselves with pending state legislation on police stops and the use of force.

In October, we launched the Coalition for Police Reform (CPR, The Coalition). The city manager and SMPD chief agreed to meet with the new group soon after it was formed. This was the start of quarterly meetings with them and their successors, which continue to this day.

The Coalition’s action plan aims to increase equity and fairness by proposing policy revisions and the elimination of questionable practices, build community trust by promoting transparency and accountability, and promote community safety by developing a more cooperative community-police relationship. The Coalition meets monthly and has consistently comprised about a dozen activists, nearly half of whom are African American residents.

2020 protests and formation of the PSROC

Fast forward to May 31, 2020. The Santa Monica Police Department’s gross mismanagement of the George Floyd protests and the looting in Santa Monica’s major retail zone was the catalyst for the departure of the chief and the launch of the city’s first civilian oversight commission.

As a result, Santa Monica provides a case study of the dynamic relationship between a government-based oversight commission and a grassroots group that preceded it. The Coalition and other Santa Monica activists made achieving civilian oversight a high priority in the shared belief that police reform is best advanced by a semi-judicial, permanent board comprised of reform-minded individuals who are part of the community, but are not members of local law enforcement.

As SCRJ Executive Director George Brown recounted in his introductory essay for this On the Ground series, the Public Safety Reform and Oversight Commission (PSROC) formally launched in 2021. It had a rocky start. The NAACP branch president’s application to serve was disqualified because he did not reside in the city. None of the longtime Coalition activists were appointed by the City Council to the PSROC. Nevertheless, Mr. Brown’s position as chair ensured that Coalition voices were heard in its monthly meetings, and we continue to have good relationships with several of the commissioners.

Given the PSROC shortcomings that Mr. Brown described, what are the prospects for grassroots advocacy to help move a reform agenda forward in Santa Monica? More generally, what are the advantages and disadvantages of pursuing informal paths to reform in cities where weak formal mechanisms exist?

To answer these questions, I summarize below The Coalition’s main accomplishments, share my reflections on the strengths and limitations of our role, and draw lessons that I hope will be useful to activists facing similar challenges in other small cities.

The Coalition’s Work

The Coalition has focused its activities at the state and local levels.

- Since 2015, The Coalition has lobbied for state legislation, including CA Assembly Bill 392, which changed state law for police use of force from what is “reasonable” to what is “necessary” and CA Senate Bill 1421 which made officers’ personnel records relating to use of force and sexual assault more public. Several of our members have been especially active at meetings of California’s Racial and Identity Profiling Advisory Board, tasked with implementing CA Assembly Bill 953, which mandates that police officers document the stops they make. The Board included several of our recommendations in its first annual report and in several reports thereafter.

- In 2016, we made a video of first-person reports showing that segments of the community experience interactions with SMPD as discriminatory practices, based on race. I co-authored a paper with a RAND public policy graduate student addressing the problem of racial bias in police stops and recommending actions that should be undertaken by SMPD to increase community trust.

- Robbie Jones, a member of The Coalition, proposed an African American Community Academy for Police (AACAP) as a complement to SMPD’s academy for residents. The idea is that officers need to learn about the history and lived experience of Black residents and engage with them directly during training. In early 2017, the chief directed the captain who leads the procedural justice course to work with us to enact an aspect of this proposal. In the next offering of his course, the captain added a Black community history tour, followed by African American residents’ participation in classroom training exercises. Based on our conversations with the new Chief, we are confident that the Academy will be reinstated.

- In August 2020, I made an invited presentation to the advisory committee that preceded the PSROC. My oral and written summaries of recent Campaign Zero rankings of SMPD compared to 99 other California police departments showed that our department had larger racial disparities in policing than nearly all of them. Subsequently, a captain made available to us over two years of SMPD statistics on field contacts, citations and arrests, which supported the Campaign Zero rankings. We used these data in our subsequent work.

- Our requests for quarterly meetings have been honored by all four city managers and four police chiefs serving since Spring 2015. Prior to each of these meetings, several Coalition members who plan to attend agree in advance to each introduce a different topic for discussion.

- Independent of issues we raise in quarterly meetings, we have used the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) twice to advance our work. In the first instance, we used FOIA to obtain a copy of a November 2016 Memorandum of Understanding between the chief and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). It turned out that the agreement had not been approved by the city manager and could be interpreted as involving SMPD in civil immigration enforcement. Our objection resulted in cancellation of the agreement. In the second instance, we obtained Santa Monica jail video, monitored jail management, and met with jail representatives to raise concerns that due process rights were not granted in a timely manner to persons following their arrests.

- Occasionally we have used iPhone videos taken by us or sent to us by others to document our concerns and influence decision-makers. For example, one of our members video-recorded and posted on social media the arrest by SMPD of a Black male bicyclist who refused to provide identification when stopped for riding on the sidewalk. We visited him in jail, sent emails on his behalf to city officials, and monitored his court dates. The City Attorney dropped the case against him.

Reflections on Our Grassroots Advocacy

The Coalition didn’t fold its tent when the PSROC was launched early in 2021. We monitor its activities and speak up during its meetings. However, the shortcomings of the PSROC’s mandate and authority highlight the need for The Coalition to continue advocating for reform independently.

The larger point is that there are distinct advantages to pursuing police reform as a nongovernmental grassroots collective. Not the least of these is that we leverage the diverse skills of our individual members: lived experience, social connections to decision-makers, number crunching, and knowledge of local Black history. The Coalition provides a way for its members to combine their skills and coordinate their efforts. Working together generates benefits that are internal to the group, as well. Among the natural byproducts of participating in a collective are network building, social cohesion, and learning new skills. The group also provides a degree of anonymity for activists who are undocumented or have other status vulnerabilities.

Grassroots work typically results in reforms that are discretionary and lack the permanence which independent civilian oversight of law enforcement could achieve. Nevertheless, in cities that lack civilian oversight authority, grassroots action can help fill the gap. And in cities that have civilian oversight, coalitions like ours can spur the official body to action while advocating for reforms in their own right.

Photo sources: MrSantaMonica.com (top Nat Trives photo); Michele Wittig’s personal files; Committee for Racial Justice Facebook page (bottom photo)