Arthur Rock’s Intel Memo

The Magna Carta of Venture Finance

Arthur Rock’s brilliantly concise memo, drafted in 1968, describes Intel’s initial financing, governance, and employee incentive structure. It may well be the most important single document in Silicon Valley history and is, we think, venture capital’s Magna Carta. In fewer than four spartan pages, Rock defines a model that continues to dominate the venture capital process more than fifty years later. Indeed, much of today’s venture capital deal structure is simply a variation on the theme set forth in this brief document.

To appreciate the memo’s significance, it is essential to recall the context in which it arose. In 1968, Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore were among the “traitorous eight” engineers who had left Shockley Semiconductor a decade earlier to establish Fairchild Semiconductor. In leaving Shockley, they planned to build a more egalitarian, engineer-focused company. Rock, who was part of the team that put together the financing for Fairchild, had urged the eight to strike out on their own. He understood that having founders own a stake in their own company could be a powerful motivator for success. Indeed, Fairchild’s early years were a testament to this insight: With each founder providing $500 of seed capital in exchange for 100 shares, Fairchild’s early years buzzed with creativity and profit.

The problem, however, was that in securing its initial financing, Rock found that few investors were interested in backing such an organization. The lone investor Rock managed to secure, Sherman Fairchild’s Fairchild Camera and Instrument, could therefore impose onerous terms. Fairchild agreed to back the new venture only if it had an option to buy the company for $3 million. With orders for semiconductors flowing to Fairchild Semiconductor in 1959, Fairchild exercised its option. The move provided a handsome return to its founders but relegated them once again to the rank of employee rather than owner.

When Noyce and Moore decided to leave Fairchild in 1968 to form Intel, they reached out to Rock to once again try their hand as founders. All agreed to build on the Fairchild experience. Then, as now, the challenge was to define a financing arrangement that provided a sufficient return to Intel’s investors while also offering strong incentives for Noyce, Moore, and the other employees to grow the company. Failure to balance these objectives had been Fairchild Semi’s Achilles’ heel. Moreover, investing in Intel called for a concentrated bet on a single firm at the very same time that the mantra of diversification was spreading like wildfire in the investment community. Intel’s investment terms would have to address this concentration risk.

Arthur Rock’s memo addressed all these concerns through a combination of pricing, incentives, terms, and governance in a manner that still reads as contemporary even though the document is now decades old.

Pricing. To a first approximation, venture finance is about the ownership split between founders and investors. For founders, how much ownership must they cede to investors in exchange for capital? For investors, what ownership stake is appropriate risk-adjusted compensation for that capital? Before Intel, deal terms often skewed strongly in favor of investors, leaving little incentive for founders to grow the business. Rock’s proposal was different. His financing would raise $2.5 million for the company, with a prefinancing value on the company of $2.5 million. Today, we would call that the pre-money valuation. The founders and investors thus effectively split the upside equity stake in the company 50-50, respecting the principle that, in this transaction, the founders brought as much to the table as did the investors.

Moreover, unlike the Fairchild transaction, there was no investor option to purchase the company if it succeeded. The potential return on the founders’ sizable ownership stake was therefore uncapped and created powerful incentives to grow Intel as quickly and as dramatically as possible. Today, the first page of every term sheet begins with an express description of the pre-money valuation and the investment amount. Those terms provide a clear understanding of the ownership split envisioned by the financing. In the Rock memo, the ownership split was implemented by valuing the founders’ 500,000 shares at a sizable discount to the $5 per share investors would pay for their 500,000 shares when they converted the investment security issued in the financing (discussed below). This two-tier pricing between founders and investors continues to this day—a mechanism that allows for the desired ownership split to be implemented without forcing founders to pony up cash they might not have.

Incentives. While the ownership split provided powerful incentives for founders, the Rock memo also turned conventional management on its head by envisioning all employees as owners. The idea that employees need incentives beyond the command-and-control world of the traditional firm ran counter to management orthodoxy of the time but was vital to avoiding the employee exodus that ultimately doomed Fairchild Semiconductor. As with pricing, the notion of broad-based equity participation in connection with a venture capital financing remains standard practice today.

Security terms. To account for the significant risk associated with the investment, the Intel memo provided for terms specifically designed to protect investors if the venture failed to thrive. Most notably, the investors received a subordinated note that was convertible, at the holder’s option, into shares of Intel’s common stock. In other words, the 50-50 ownership split envisioned in the memo was premised on the assumption that Intel’s common stock would be worth more than $5/share. Only then would the investors rationally convert their note into common stock and participate in the company’s growth alongside the founders. If Intel failed to achieve this valuation by the time of a sale or liquidation, the investors would be somewhat protected because they would be entitled to be repaid as noteholders ahead of the common stock (though after all other fixed claims). Today this type of subordinated convertible instrument is implemented via convertible preferred stock, but the fundamental economic principle is identical to the model articulated by the Intel memo.

Governance. Finally, as an additional risk-mitigation and success-enhancing device, the Rock memo defined a governance structure that had founders and investors sharing control of Intel’s board, while also bringing on outside directors with relevant industry experience. This structure helped ensure that investors had some degree of oversight and control over Intel as the company navigated an uncertain future. It also helped address the enhanced risk created by the concentrated ownership position the investors would have in the venture. Again, it is a structure that is all too familiar to contemporary venture capitalists.

For these reasons, it is fair to say the Rock memo provided a key, foundational template for the subsequent evolution of entrepreneurial finance. It encapsulated a philosophy that embraced and balanced risk, innovation, and autonomy, with the need to provide strong incentives to align founders’ interests with those of the company’s investors. Like the Magna Carta, it was a declaration of change. It proclaimed a new era. It established a model that would define the future of the U.S. venture capital ecosystem for decades to come. For more on the Rock memo, go to https://stanford.io/3MTEcov and the Q&A with Rock https://stanford.io/43dnMx6. SL

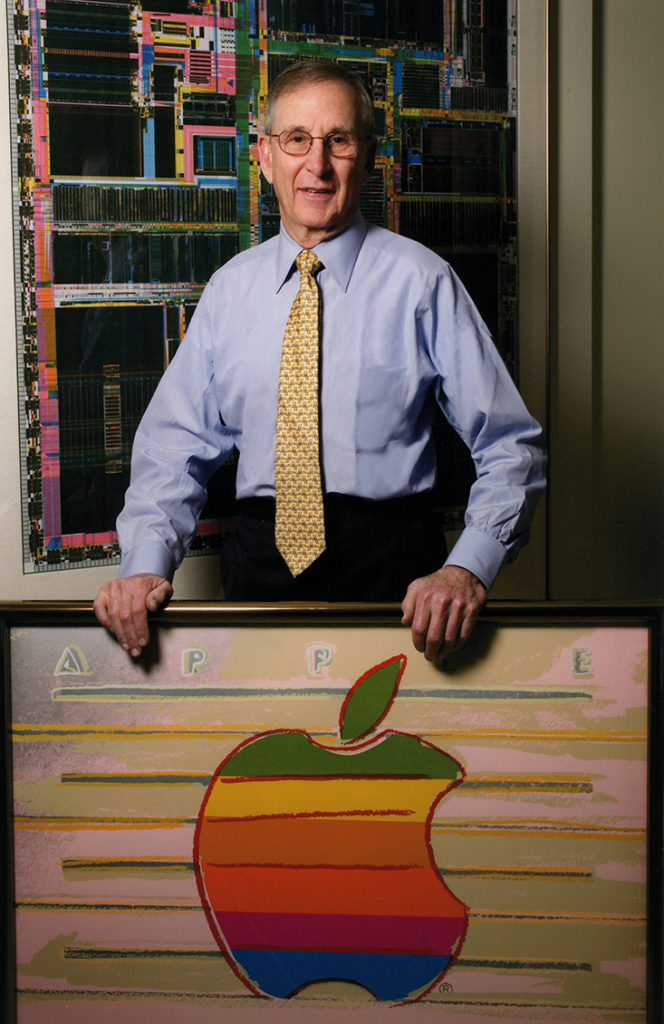

Joseph Grundfest, JD ’78, is the W. A. Franke Professor of Law and Business, emeritus, and senior faculty at the Rock Center for Corporate Governance. Robert Bartlett joined the faculty on July 1, 2023, and is the new William A. Franke Professor of Law and Business.