Copyright’s Highway Take 2

U.S. copyright law has been besieged by critics and stalled through congressional inaction as digital technology has quickly evolved far beyond early efforts of lawmakers to harmonize statutes and software. Aiming to clarify the legal complexities surrounding the internet’s capacity to bring books, movies, and music to anyone with a broadband connection, Paul Goldstein, the Stella W. and Ira S. Lillick Professor of Law, has now amplified his earlier insights with an update of his seminal work, Copyright’s Highway: From Gutenberg to the Celestial Jukebox, which was first published in 1994 and revised in 2003.

“A funny thing happened to American copyright on its way to the twenty-first century,” is how Goldstein opens the book’s new Chapter 8, a 50-page recap of how his metaphoric jukebox has moved beyond the now-ancient litigation over the Napster file-sharing service and enactment of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. That 1998 law included anti-circumvention and safe harbor. But since then, there has been silence from Congress. “After two hundred years of regularly expanding to bring new technologies within its embrace, copyright effectively came to a dead halt.”

And, despite the challenges presented by more recent internet giants such as Google, Facebook, and Twitter, the legislative mill gives few signs of restarting.

“In the last fifteen years, as much has happened as in the previous one hundred years,” says Goldstein as he sits down for an interview in his office. But legislative efforts to keep up have gone nowhere because “the battle between the industries film, music, and publishing and the internet platforms has made it very hard for Congress to move. Before, everything was done by compromise.”

What the filmmakers, music studios, and publishers had going for them was the implicit acceptance that copyright was a good thing, Goldstein says, adding, “That’s a premise I share deeply.” But mistakes were made. “A series of missteps by the copyright industries has demonized copyright in the public mind, starting in the 1980s with the debate over copyright protection for computer software.” The internet companies sought and won protection for their code, even though copyright isn’t supposed to be about functionality. That was once patent law’s exclusive realm. “The capper,” Goldstein says, “was the 1998 extension of copyright terms—adding 20 years of protection not only to future works but to works that had already been created, saving Mickey Mouse and other iconic entertainment products that were about to fall into the public domain.

“The media jumped all over the law, but only after it had passed, and copyright for the first time became truly a grassroots issue when Larry Lessig [then on the Stanford Law School faculty] took it up to the Supreme Court. He lost there, not because term extension was a good idea, but because it wasn’t an unconstitutional one,” says Goldstein.

The congressional vacuum has been filled by courts seeking to adjust copyright to the new internet technologies—but in piecemeal fashion. “They have done so principally—and in some cases aggressively—through the fair use doctrine,” he says. Goldstein is critical of stretching fair use’s “transformative” standard as far as judges have done, especially when they OK’d Google’s unauthorized digitization of tens of millions of books, and he’s worried about impairing publishers’ ability to profit from licensing their own digital versions. In his new Chapter 8 he observes, “Effectively, in this important market the publishers now had to compete with free.”

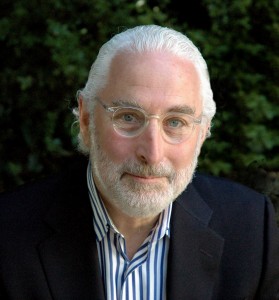

Goldstein’s expansion of Copyright’s Highway will only augment his stature as copyright guru. Other milestones on this road include his lengthy tenure as a Stanford Law professor, his treatises on U.S. and international copyright law, his elevation to Intellectual Asset Management’s IP Hall of Fame, his of counsel status at Morrison & Foerster LLP, and his teaching awards.

“Paul has been the preeminent scholar of copyright law for the past 50 years,” says Mark A. Lemley, the director of the Stanford Program in Law, Science and Technology. “His work has influenced generations of courts, scholars, and lawyers.” There’s Goldstein on Copyright in five volumes with semi-annual supplements, International Intellectual Property Law: Cases and Materials, and, for the sophisticated law audience, Copyright’s Highway.

And then there’s the tree, Stanford’s emblem made manifest in the mighty redwood that now soars past his third-floor Neukom office window. Back in 1975, when he assumed his Stanford professorship, the tree, newly planted, was about 10 feet tall.

“There’s a certain poetic symmetry to that tree,” Goldstein says, “Early on, I was in an office across the way when it was still a sapling.” His face is framed in a silver beard and coif. He’s all in black, down to his highly polished brogues. “And now 40 years later, I find myself in a new office in a new building, with a view of the same tree. So, it’s poetry in the sense of the observation attributed to Mark Twain that history doesn’t repeat itself, but sometimes it rhymes.”

Goldstein’s influence in the field has grown alongside the conifer, his views captivating students and future IP lawyers. “Professor Goldstein’s introduction to intellectual property course had a profound effect on the direction of my career,” says Stanford Law grad Kelly M. Klaus, a Munger, Tolles & Olson LLP litigation partner who has represented major movie studios and record companies. “From the time I took that class, it was my goal to practice in the area of copyright, and I owe all of that to Professor Goldstein. He is an incredible scholar, teacher, and mentor.”

Michelle K. Lee, a former director of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, is currently a visiting professor at Stanford. “Like many generations of Stanford Law grads, I had Professor Goldstein for introduction to intellectual property,” she says. “Professor Goldstein confirmed my interest and passion for the topic with his eloquence and ability to bring the subject to life.”

“He’s incontestably the number-one academic in copyright in the U.S. He’s had a tremendous influence on the field, and I admire him tremendously,” says Jane C. Ginsburg, the Janklow Professor of Literary & Artistic Property Law at Columbia Law School. “When I was starting out, Paul was very supportive and generous, with his comments and as a mentor, helping me even though we were from different institutions.”

On the Neukom hallway that he and neighboring colleagues have designated a “quiet corridor” to facilitate thoughtful scholarship, Goldstein has established a calm shelter from the ongoing IP storms by means of his steadfast insistence on copyright’s centrality. “In three hundred years,” he says, “society has not come up with a legal system better structured to encourage the production of the widest variety of creative work at the lowest possible price.”

And like so many of the artists that copyright laws help to protect, Goldstein is himself a creator. He has produced a quartet of gripping legal thrillers starring alcoholic attorney Michael Seeley; the third in the series, Havana Requiem, won the 2013 Harper Lee Prize. A 2017 satire, Legal Asylum: A Comedy, features law school dean Elspeth Flowers, who will stop at nothing to get her small-time school into the U.S. News & World Report’s Top 5 and herself onto the Supreme Court, where she dreams of frolicking naked beneath her robes. Her faculty boasts an IP prof who believes all property is theft. “I had to get in someone from the so-called copyleft movement,” Goldstein says. “The book was a lot of fun to write.” Did the plot get him in trouble with disapproving colleagues? “Not as much trouble as I had hoped,” he laughed.

Regarding the impasse that currently stalls the development of copyright law, Goldstein said a solution is near. He pointed out that Google and other internet companies have had a long, unregulated run. “The argument that they need to be free from regulation to be able to innovate has grown thin,” he says. “But as their operations draw ever closer to those of traditional media companies, pressures will grow to subject them to the same kinds of rules that apply to traditional media.” He offered as an example new interest in Congress in the fake news disinformation threat and what some lawmakers have called Facebook, Google, and Twitter’s unsatisfactory response. “As the playing field grows more level, the question of appropriate copyright restrictions for the internet companies seems likely to emerge as well.”

“I believe in copyright’s historic ability to organize markets for information and entertainment—to get as wide a variety of creative works into as many hands as possible. I have greater faith in copyright to accomplish that than I do in any particular business model.”

Goldstein’s office walls display framed black-and-white photographs he’s taken with an old Leica and an artist’s fresh eye. One shows the strong contrast between a sidewalk café table’s umbrella and its dark shadow. “I principally do street photography, and I have a long-term project trying to capture some of the more surreal aspects behind the banal surfaces of the Palo Alto landscape,” he says, before acknowledging that every photo is protected by copyright.