Sandra Day O’Connor, LLB ’52 (BA ’50), First Woman to Sit on the U.S. Supreme Court, Dies at 93

O’Connor was a pivotal voice on the high court for more than two decades; after her retirement, she devoted her professional life to improving civic education

Sandra Day O’Connor, LLB ’52 (BA ’50), a rancher’s daughter who grew up in a house without running water and went on to become the first woman justice on the U.S. Supreme Court, died on Friday, December 1. She was 93.

“Justice O’Connor had such an important and distinctive impact on American law,” said Stanford University Provost and former Stanford Law Dean Jenny Martinez. “She was of course a pioneer as the first woman on the Supreme Court. Her approach to law was pragmatic and reflected the spirit of freedom and openness of the American West, based on her time growing up on a ranch in Arizona and then of course here on “the Farm” for law school.”

Provost Martinez continued, “She was also an incredible mentor and role model to so many young women in law. When I was clerking for Justice Breyer, BA ’59, she went out of her way to get to know the clerks in other chambers, including through her famous morning exercise class at the Court. And years later when I was on the faculty here and saw her at conferences and events, she was always so warmly supportive. I’m so proud that Stanford was a part of the journey of such a remarkable, historic figure.”

“Justice O’Connor was a person and jurist of integrity and grit,” said Bernadette Meyler, JD ’03, Carl and Sheila Spaeth Professor of Law. “She was an incredible role model for women of my generation and particularly inspired those of us who attended Stanford, her alma mater, to believe we could achieve what we had set out to do.”

“Her political experience was reflected in her sophisticated opinions, sometimes for the court and sometimes in separate writing, regarding pivotal issues in the law of democracy, ranging from political gerrymandering to minority vote dilution to excessive race consciousness in the political process,” said Pamela Karlan, the Kenneth and Harle Montgomery Professor of Public Interest Law at Stanford.

O’Connor’s journey to the highest court in the land began in a class she took as an undergraduate at Stanford University with Professor Harry Rathbun, JD ’29 (BA ’16, Engr. ’20). She was so inspired by his life and teaching that she decided to apply for early admission to Stanford Law School.

“His impressive knowledge, his manner, and his mind impressed me greatly,” she said at a 2009 memorial for Rathbun. “I thought one reason he was so effective was his legal training and his logic.”

O’Connor’s first legal job, during the summer before she began law school, was as a secretary for an attorney in Lordsburg, New Mexico, whose clients included a bookie and a brothel owner; and she famously could not find a job after graduating despite being in the top 10 percent of her class because so few firms would hire women at the time. But O’Connor was undeterred. Over the years, she worked for the U.S. Army, in private practice, and as a state legislator and judge before receiving the nomination from President Ronald Reagan that would change her life and history.

“His decision was as much a surprise to me as it was to the nation as a whole,” O’Connor said years later. “But Ronald Reagan knew that his decision wasn’t about Sandra Day O’Connor; it was about women everywhere. It was about a nation that was on its way to bridging a chasm between genders that had divided us for too long.”

From the Ranch to the Farm

O’Connor was born on March 26, 1930, in El Paso, Texas, and grew up on her family’s sprawling Lazy B Ranch, 250 square miles of cattle grazing country located half in Arizona and half in New Mexico. The oldest of three children, she was sent at a young age to live with her maternal grandparents in El Paso to attend school. She preferred life on the ranch, however, where her first pet was a bobcat and she learned to ride on a horse named Chico.

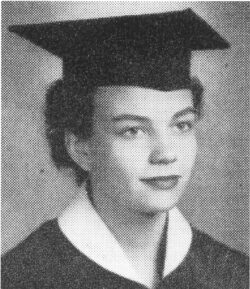

O’Connor chose Stanford University because her father had wanted to attend the school before he was called upon to run Lazy B; she was the only student in her class to apply to an out-of-state college and began her freshman year when she was 16.

She completed her BA in economics in three years and enrolled at Stanford Law School during her fourth year as an undergraduate in what was known then as the 3-3 program. During the summer before she matriculated and following her 1L year, she worked as a secretary for an attorney who worked in town near her family’s ranch. The lawyer handled wills and contracts and also most of the major criminal cases in the area, including defending a bar owner who operated an illegal gambling ring and a woman who was said to run the largest brothel in the country.

At Stanford Law, O’Connor quickly made her mark in more ways than one. She was an editor on the Stanford Law Review; helped, with fellow classmate and future Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist, LLB ’52 (BA/MA ’48), negotiate a “tyrant” professor’s return to lecturing; and reportedly received four marriage proposals (from Rehnquist and three others). The most important of those came from John O’Connor, LLB ’53 (BA ’51), whom she met when they were both assigned to edit a law review article. When she brought him home to meet her parents on the Lazy B Ranch, her father served him freshly castrated bull testicles— “mountain oysters”—cooked impromptu over a branding fire. The couple were married in December 1952.

Raising a Family and Political Pursuits

O’Connor, who was one of only five women admitted to the SLS Class of 1952, described many times over the years how she could not find a job after graduation (one firm she interviewed with asked her how well she typed to see if she might be a good candidate for secretary); eventually, she offered to work for free in the San Mateo County District Attorney’s office. She was later hired as a deputy district attorney and worked mostly on civil cases. From 1954 to 1957, the O’Connors lived in Frankfurt, Germany, where John was an attorney in the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General’s Corps, and O’Connor worked as a civilian lawyer for the Quartermaster Market Center System, which procured goods for the Army.

The couple settled in Arizona. O’Connor had her own practice—in an office in a strip mall—while also raising three boys. When her babysitter moved to California, she stayed home with her children for about five years, becoming active in local politics. In 1969, the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors appointed her to fill a vacancy in the state senate; she successfully ran for the seat in 1970 and 1972, when she was elected by her Republican colleagues as the first woman state senate majority leader in the United States.

As a legislator, O’Connor worked to remove sex-based references in state laws, to reform community property laws that disadvantaged women, to reinstate the death penalty, and to support Medicaid, among other issues. She also wrote to President Nixon in 1971 asking him to appoint a woman to the U.S. Supreme Court (in October of that year, he nominated two men, including Rehnquist).

In 1974, she became a judge in the last election to the Maricopa County Superior Court; in 1979, Governor Bruce Babbitt appointed her to the Arizona Court of Appeals.

The First, But Not the Last

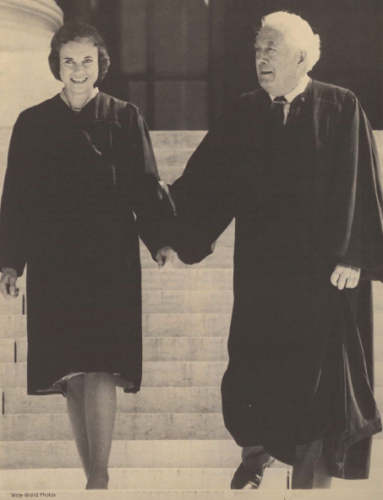

When President Reagan nominated O’Connor to fill the seat of Justice Potter Stewart on the U.S. Supreme Court, papers around the world covered the news; People magazine sent photographers to the Lazy B Ranch. Current Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr. helped prepare O’Connor for her Senate confirmation proceedings (the first time such a hearing was televised live), but she didn’t need much help: the vote was unanimous in her favor.

“When I was a junior professor, I was delighted to make Justice O’Connor’s acquaintance when she was the commencement speaker for the university, and also appeared at the law school ceremony,” said Robert Weisberg, JD ’79, SLS interim dean and Edwin E. Huddleson, Jr. Professor of Law, who was a clerk for Justice Stewart. “From this first introduction, I was deeply touched by her evident intellectual and moral grace and empathetic professional judgment, all well proved by her wonderful service on the court.”

On the high court, O’Connor was known for crafting narrow opinions; she was often the deciding vote in controversial cases and was known as the swing justice. But she did not care for that label.

“I’ve never gone along with the notion of a swing vote,” she said at the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals conference in 2000. “In any case, if there were five on one side, that’s enough to reach a holding of the court, and every one of the five counts just as much as every other one. And so I got a little impatient with that.”

By the time she retired in 2006, O’Connor had written 645 opinions, including landmark decisions upholding gender equality (1982’s Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan), the right to abortion (1992’s Planned Parenthood v. Casey, coauthored with Justices Kennedy and Souter), and affirmative action (2003’s Grutter v. Bollinger). She also joined the majority—and, according to recently revealed documents, circulated an early influential memo—in the case that decided the 2000 presidential election in favor of George W. Bush.

According to her clerks, O’Connor worked exceptionally hard, but she also knew how to enjoy life. She cooked meals regularly for her law clerks; planned excursions for them in D.C. and around the country; and enjoyed fishing, golf, tennis, and skiing. She and John loved dancing so much they installed a dance floor in their home in Arizona. Above all, O’Connor prioritized her family and personal life.

“You start there and you end up there at the end of the day,” she told her former clerks in 2015, and “when you can’t do anything, they have to take care of you.”

“Justice O’Connor literally forged the path that my life has followed. Seeing her join the Supreme Court made me feel as a fourth-grade girl that I could aspire to anything,” said Judge Michelle Friedland, B.S. ’95, J.D. ’00, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. “I eventually had the great privilege of clerking for her and got to see up close her dedication to the rule of law, tireless work ethic, and respectful and warm approach to every person she encountered. Her commitment to helping her clerks with their personal and professional lives never ceased. Even after her health started declining, she attended the Senate hearing on my judicial nomination and came to the Ninth Circuit to swear me in once I was confirmed. I would truly not be here today if not for her, and words cannot capture how grateful I am to her and how much I will miss her.”

‘The Most Important Work I’ve Ever Done’

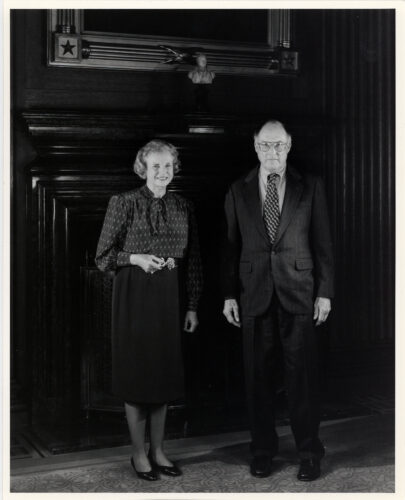

When O’Connor retired in 2006, it was to take care of John, who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 1990. She did not retire from public service, however. She served as a visiting federal appeals court judge for many years and, in 2009—the same year John died—launched iCivics, an organization that creates non-partisan civic education resources, including video games. She called iCivics “the most important work I’ve ever done.”

“It is the notion that young people across this country need to have some idea of how our government works and how it functions and how they can be part of it,” she said in the 2015 interview. “It was my effort to make sure we taught them something.”

In 2018, O’Connor stepped back from public life, announcing that she had been diagnosed with the disease that eventually took her husband’s life. But her legacy lived on, even as many of her precedents were overturned by an increasingly conservative court. In 2023, USA Today named her one of its Women of the Year.

In speeches throughout her career, including a commencement address at Stanford in 2004, O’Connor often recited from “The Bridge Builder,” a poem by Will Allen Dromgoole that describes a man who builds a bridge after crossing a vast chasm. When a passerby tells him he is wasting his time since he no longer needs to cross the divide, the man answers that he is building the bridge for those who might follow.

O’Connor was likewise a trailblazer, and she recognized the responsibility. Often, when discussing her historic appointment to the Supreme Court, she gave a nod to the need to nurture the next generation of leaders.

“It’s good to be first,” she would say. “But you don’t want to be last.”

O’Connor is survived by her three sons, Scott O’Connor, BS ’79, Brian O’Connor, and Jay O’Connor, AB ’84; six grandchildren; and her brother and co-author, Alan Day, Sr. Her husband, John O’Connor, preceded her in death in 2009 and her sister, Ann Day, a former Arizona state senator, died in 2016.