Stanford Center for Racial Justice Brings Transparency to the Rules Governing Police Use of Force

Five years after the murder of George Floyd sparked a national reckoning, police departments across the United States have rewritten, or pledged to rewrite, their use-of-force policies. Yet it has been extraordinarily difficult to see how those policies compare, where meaningful reforms have taken hold, and where gaps remain.

Now, thanks to a new three-pronged research initiative from the Stanford Center for Racial Justice, police use-of-force rules from across the United States are accessible and comparable at an unprecedented scale.

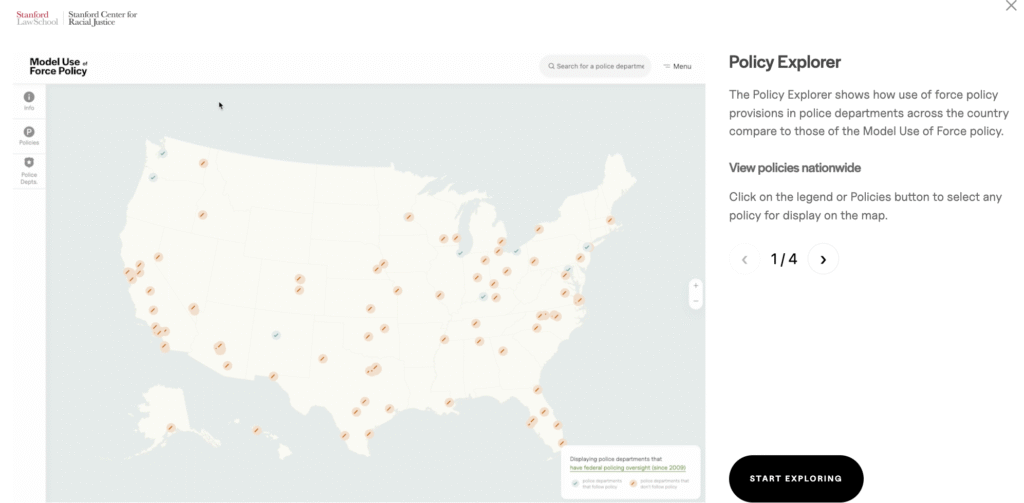

At the center of the initiative is a recently launched, first-of-its kind database, the Use of Force Policy Explorer. The searchable website equips communities, policymakers, and law enforcement agencies with concrete tools to evaluate and strengthen the rules that govern police encounters.

Underpinning the Policy Explorer is an ambitious new report, “Police Use of Force Policies Across America,” co-authored by Dan Sutton, the Center’s director of justice and safety, and former research associate Fatima Dahir. Drawing on 11,000 pages of policy documents and a systematic analysis of 2,200 policy provisions across the 100 largest U.S. cities, the report is believed to be the largest empirical study of American use-of-force regulations to date.

The third prong of the project is a comprehensive model use-of-force policy designed to translate the study’s findings into a practical framework departments can adapt to their own legal and operational contexts.

Ralph Richard Banks, the Jackson Eli Reynolds Professor of Law and faculty director of the Stanford Center for Racial Justice, said the initiative fills a long-standing gap in public understanding. “Use-of-force policies shape some of the most consequential encounters between the state and the public,” Banks said. “Yet those rules have typically been buried in department manuals and are difficult for policymakers to evaluate. This project brings unprecedented transparency to those decisions—and gives communities a clearer basis for assessing whether their local rules reflect their values.”

Try the Use of Force Policy Explorer

The Report: Wide Variation and Positive Shifts

The analysis reveals stark differences in how police departments regulate force. While a growing number of large-city departments now require officers to attempt de-escalation before using force, some departments—including Chesapeake, Virginia, and Lincoln, Nebraska—still permit officers to draw or point firearms during routine encounters, even when no immediate threat is present. Twenty departments don’t require officers to de-escalate before using force. Only 41 restrict the use of pepper spray on handcuffed individuals. And just 54 clearly designate deadly force as a last resort.

Policies governing chokeholds, neck restraints, and strikes to the head remain unevenly restricted, with some departments imposing categorical bans and others relying on vague or conditional limits. The report also finds wide variation in how clearly departments define key standards—such as necessity, proportionality, and last resort—leaving officers in some jurisdictions with far more discretion than in others.

The study also reveals a positive trajectory of change: 92 departments now ban chokeholds, up from 22 a decade ago. And 93 now require officers to intervene when they witness misconduct, compared to 29 in 2015.

“What stood out was not just the degree of variation, but the kinds of choices departments are making,” Sutton said. “Some have tightened the rules around when force may be used. Others continue to allow wide officer discretion in routine encounters. Seeing these policies side by side shows that post-2020 reform has been real, but uneven and incomplete.”

The Policy Explorer: Police Policies at a Glance

Policy Explorer users are able to see, at a glance, how policies compare across jurisdictions and click directly to the underlying policy language.

“If you want to know whether a major city’s police department requires de-escalation, restricts certain weapons, or limits deadly force to last-resort situations, you won’t have to wade through dozens of pages of online materials or track down numerous sources,” Sutton said. “The information will be there, clearly organized and publicly accessible.”

The Explorer is intended for a wide audience: community members seeking accountability, journalists covering police use of force, policymakers drafting new regulations, and law-enforcement agencies looking to benchmark their own rules against peers.

Center researchers plan to continue adding cities to the tool.

Model Use of Force Policy: Guidance for Change

The third prong of the initiative, the model use-of-force policy, translates the Center’s empirical findings into a practical framework that departments can adapt to their own legal, operational, and community contexts.

It is structured around 10 essential policy elements and developed from public health research, social science scholarship, and national best practices—building on foundational work by former Center Executive Director George Brown—with contributions from Stanford Law students, center staff, and pro bono partners at law firm Gibson Dunn.

The model policy addresses core use-of-force questions—from overarching standards like necessity and proportionality to specific rules governing weapons, de-escalation, pursuits, and other high-risk encounters. Each module includes model policy language alongside explanatory materials that clarify the legal and policy choices involved, helping departments understand not just what a policy says, but why it matters.

“The goal is not to impose a one-size-fits-all solution,” Sutton said, “but to give policymakers and law-enforcement leaders a well-supported starting point for strengthening their own standards.”

Read a USA Today op-ed by the authors of the study

About Stanford Law School

Stanford Law School is one of the world’s leading institutions for legal scholarship and education. Its alumni are among the most influential decision makers in law, politics, business, and high technology. Faculty members argue before the Supreme Court, testify before Congress, produce outstanding legal scholarship and empirical analysis, and contribute regularly to the nation’s press as legal and policy experts. Stanford Law School has established a model for legal education that provides rigorous interdisciplinary training, hands-on experience, global perspective and a focus on public service.