Private Universities in the Public Interest – White Paper

WHITE PAPER

Private Universities in the Public Interest

Renewing the relationship between American universities and society to address the most pressing challenges of our time.

Ralph Richard Banks, Emily J. Levine, Emily Olick Llano, Hoang Pham, Mitchell L. Stevens, and Dan Sutton

Stanford Center for Racial Justice

Published: November 1, 2024

Download White Paper :

Introduction

America’s leading universities are envied worldwide but face growing enmity at home. By many measures—research productivity, student selectivity, endowment wealth, and global rankings—the top 50-100 institutions in the United States are thriving. Yet these same schools face growing skepticism, resentment, and outright derision from the public and politicians alike. Wealthy and admissions-selective schools, especially, have become flashpoints in the economic and political divisions of our time. Prominent journalists and academics regard them as implicated in a “meritocracy trap”[1] that primarily serves the interests of the already privileged.[2] Conservatives call them bastions of self-congratulating liberals.[3]

On many counts the larger postsecondary enterprise is in trouble as well. Student loan debt poses a serious threat to the financial security of millions of Americans.[4] Six-year completion rates for those seeking four-year college degrees hover around 64 percent.[5] Perhaps most sobering: possession of a four-year college degree has become a signal dividing line in our national life, distinguishing those who can reasonably expect stable employment and healthier lives from those who cannot[6] and increasingly predicting patterns of voter behavior.[7] All of this is rightly giving many scholars and academic leaders pause.

This paper frames the current predicament of U.S. higher education in the context of its history. We do so to motivate proactive change from within the academy itself. Drawing on a wide range of recent scholarship, we explain how and why Americans came to admire and generously subsidize higher education over the long arc of our nation’s history. Time and again, elected officials, ambitious entrepreneurs, and everyday citizens have relied on colleges and universities in the interest of national progress. They have called on colleges and universities to settle frontiers; fight world wars; and remediate racial and socioeconomic inequality. And universities have responded in turn, nimbly adapting in form and function to meet the needs of changing times.

Huge investments in higher education across multiple generations have woven colleges and universities into the fabric of our national life. In a peculiarly American form of nation-building, colleges and universities were supported by public and private funds, through agreements which comprise what we call the academic social contract: a reciprocal and often implicit agreement in which money, autonomy, and prestige have been extended to universities in exchange for their tangible service to society.

Universities face great criticism now because, over time, Americans have come to expect universities to be servants and problem-solvers. They expect universities to welcome and enroll students regardless of their socioeconomic background. They expect universities to be civic spaces that convene and honor people across a wide political spectrum. Yet in recent years, many Americans have begun to doubt that such expectations are being met, and to question whether public investment in higher education pays off for the nation as a whole. University leaders might prefer to see this growing skepticism as a kind of public-relations problem, a function of poor marketing and messaging. But the problem is much deeper than that. For their very existence, universities rely on the trust and massive subsidy of everyday citizens. The historically unprecedented erosion of public faith in universities in recent years poses a profound challenge to the enduring vitality of U.S. higher education. Understanding the deep origin of this problem is an essential step in resolving it.

We recognize that the national postsecondary ecosystem is vast and diverse. We acknowledge that opportunity-expanding and occasionally transformative work is underway in some of America’s community colleges, public research institutions, and minority serving colleges and universities. Our focus is on a small yet particularly influential component of that sector: private institutions with large financial endowments and selective admissions. These schools are our focus for two reasons. First, the relationship between these schools and society has become increasingly asymmetrical. Although they are not technically public institutions, they benefit from tremendous subsidies – billions of dollars annually in exemptions from federal income taxes, state and local property taxes, and charitable deductions for their donors.[8] However, unlike America’s leading public universities, these titularly private institutions set their own priorities and are largely accountable only to themselves.

Second, well-resourced institutions have considerable capacity for autonomous action. If current growth trends continue, the private universities with the 10 largest endowments may collectively control several trillion dollars by 2055.[9] This trend is politically unsustainable. We believe that the current moment in academic and national history both enables and obliges these schools to pursue novel forms of civic action.

Our work below proceeds in three parts. We first identify the origin and evolution of the academic social contract in the United States over time. This history has gone largely unrecognized by all but a few academic specialists; surfacing it is important because it enables a fresh understanding of often implicit expectations Americans have about how colleges and universities should serve the larger society. Second, we detail how shifts in global geopolitics, the U.S. economy, and academic status systems have changed since the close of the twentieth-century Cold War. We frame these changes, collectively, as the fundamental cause of Americans’ declining faith in postsecondary education. Finally, we offer provocations for how university leaders might proactively respond to those tensions in ways that make sense for our time.

Origins and Evolution of the Academic Social Contract

Webster defines a social contract as “an actual or hypothetical agreement among members of an organized society or between a community and its ruler that defines and limits the rights and duties of each.”[10] Legal scholars, philosophers, and social scientists invoke this idea to describe the agreements among diffuse parties about how collective action and well-being are to be sustained. In addition to the agreements that govern political rulers and their subjects, examples include the public subsidy and wide discretion parents are given in exchange for bearing the responsibility of raising their own children, and the reciprocal attention, deference, and rule-following that enable automobile drivers to safely navigate vehicles in tandem with millions of others. Social contracts accrete, endure over time, and are carried across generations by careful preservation and tutelage. They also evolve as parties iterate on their terms to accommodate changing circumstances. For example, contemporary parents have far less discretion over the use of violence to discipline their children than in previous generations. Traffic laws are continually revised, and norms about what makes for courteous driving vary across time and region.

The idea of the academic social contract refers to the agreements university leaders negotiate with their patrons—governments, philanthropists, and taxpayers—to secure the material resources and autonomy essential to the academic enterprise.[11] Universities are organized around the production of knowledge and learned people, not profit. This means that they are forever courting patrons who are willing to support the academic enterprise in exchange for tangible benefit. Because compensation in gratitude or bestowal of status is rarely sufficient to elicit the kinds of support that academic projects require, entrepreneurial academic leaders have long been on the lookout for ways in which the core functions of universities can be flexed and extended to secure patronage. The renegotiation of academic social contracts is a key source of sustaining institutional innovation.[12]

While virtually all nation-states negotiate their own academic social contracts,[13] the phenomenon played out in a peculiarly elaborate way in the United States. In a nation skeptical of large, centralized government and entrenched elites, the founding and funding of colleges and universities provided ways for Americans to settle territory, grow economies, train professionals and public officials, and create civil society.[14]

Observers from other countries are often struck by the sheer number of colleges and universities in the United States: thousands of schools, of widely varying sizes and service constituencies. This is a function of America’s religious pluralism and zealous frontier expansion. The presence of a college or university in one’s region provided prima facie evidence to potential investors and settlers from the Eastern seaboard, and the Old World, that a particular place had a bright future. Schools with audacious founders and impressive buildings could literally put places on the map. Such was at least part of the intention of school founders at Chicago, Grinnell, Oberlin, Williamstown, and Wooster. Only a few of these institutions would grow to become world-class universities, but nevertheless the consequences of what the education historian Frederick Rudolph once called “college mania” was a flourishing nation-state.[15]

It came at heavy and often unsavory cost. College founders often secured funds from Christian patrons on the promise of “civilizing” native peoples and benefitted from the confiscation of physical lands whose first human inhabitants did not share the Anglo-Protestant Christians’ conception of property.[16] Equally devastating is the implication of college-founding in the history of the Atlantic slave trade. Many founders and patrons of the nation’s first schools owned slaves, exploited slave labor, and profited from their traffic.[17] Remarkably, the same religious tenets often used to justify slavery from church pulpits also were invoked to motivate abolition and African American uplift. Northern abolitionists founded schools in the upper Midwest whose stated missions included opposition to slavery; others founded schools for freed slaves after the Civil War; and African Americans founded schools in the service of individual and collective empowerment.[18] This is the undeniably ambivalent legacy of higher education with which contemporary inheritors of these institutions have only recently begun to reckon.[19]

Ultimately the early history of higher education in the United States is as complicated as the history of U.S. civil society. Colleges and universities helped to bring a new nation into existence by cultivating human capital, regional economic development, and connective tissue between public, private, and commercial activity. And they did so in ways that respected Anglo-American sensibilities of personal liberty, private property, and religious freedom. These are among the reasons Americans felt comfortable supporting private colleges with special charters, tax exemptions, and myriad direct subsidies.

The prominence of colleges and universities in our national civic landscape would prove crucial to serial war efforts, which brought the zenith of the American academic social contract around the middle of the last century. When the U.S. entered World War II upon Japan’s invasion of Pearl Harbor in 1941, it did so without the stateside infrastructure necessary for a massive multi-front military campaign. Universities filled this need. Geographically dispersed, they were well positioned to help enlist and train servicemen throughout a sprawling nation. They employed scientific and technical experts for military intelligence, communications, and weapons R&D. And they were perennially hungry for money. Contracted wartime services to the federal government in the 1940s definitively rerouted academic revenue streams. For the first time in U.S. history, Washington bureaucracies became star patrons of university research and administration nationwide.[20]

So ably did universities fulfill their service in WWII that politicians turned to universities to help absorb, reward, and “readjust” returning soldiers at war’s end. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, popularly known as the GI Bill, would subsidize the college educations of millions of returning veterans, and in the process transform Americans’ understanding of higher education. In 1940, fewer than 5 percent of U.S. adults possessed four-year college degrees. By 1990 that proportion would exceed 20 percent.[21] That it was over and above the objections of such Ivy League presidents as James Conant that the GI Bill was adopted should remind us of the challenge of wrangling various constituents to make change.[22] Despite the ubiquity of higher education and Americans’ growing affection for it, a college diploma was not yet a prerequisite for well-compensated employment nor a central mark of social esteem. The GI Bill linked college diplomas with the most prestigious category of U.S. citizenship—white male veterans—and made college access affordable and accessible to everyday people.[23]

The Soviet Union’s successful launch of the Sputnik I satellite into Earth’s orbit in 1957 prompted additional government patronage of universities. The National Defense Education Act (1958) funneled billions of dollars into academia for basic and applied research and postsecondary training in virtually every field of knowledge. Government funding to higher education became an indispensable national tool during the Cold War, contributing to weapons development, space exploration, social-science intelligence on geo-political conflicts worldwide, and international conferences and scholarly exchanges. The research-and-teaching behemoths this patronage created became worldwide standards for academic excellence and powerful symbols of “Western” democratic modernity, imitated by U.S. allies all over the globe.[24]

The U.S. federal government’s response to the rights movements of the 1960s would further engage and expand higher education. The Higher Education Act (HEA), signed into law in 1965 as a pillar of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, further democratized access to higher education in the name of gender and racial equality and the promise of education for social mobility. HEA’s direct grants and guaranteed loans put college diplomas within financial reach of most Americans who finished high school. Its financial provisions worked hand-in-glove with the expansion of state systems of public higher education in the middle of the twentieth century—through which legislatures competed with one another for the federal government’s Cold War largesse and for the prestige associated with “world-class” universities. The same federal programs supporting attendance at public universities channeled billions of dollars into private schools as well, creating a hybrid national system of postsecondary provision anchored by omnibus government funding.[25]

Businesses took advantage not only of the subsidized employee training that low-cost college represented, but also the convenience of sorting and stratifying access to coveted jobs through formal degree requirements. Within two generations, allocation of jobs shifted from reliance on informal networks to the use of college credentials as proxies for talent. By the 1970s the United States had become what sociologist Randall Collins famously called a “credential society,” in which economic opportunity and status honor were determined by their level of educational attainment.[26] By 1990, 20 percent of the U.S. adult population had obtained at least a four-year diploma and enjoyed its material and symbolic returns.[27] Admission to the privileged jobs and social networks of the upper-middle class came to require a bachelor’s degree, and the institutions purveying the most prestigious credentials—admissions-selective schools with large endowments, nearly all of which were private schools—enjoyed special prestige and deference.[28]

This was the essence of the academic social contract that defined what was often called the American century: massive government subsidy for academic research and postsecondary training in exchange for scientific R&D, diplomatic intelligence, global prestige, and a promise of social mobility through college access and attainment. It was a peculiarly American form of nation-building and social provision, and it made for a three-decade period of economic productivity, global influence, and widely shared domestic prosperity unprecedented in U.S. history before or since.

Our account of the evolution of the academic social contract would be incomplete if it did not include sports, which makes America unique among modern nation states. Soon after football was invented by college students in the 1850s, academic leaders discovered that intercollegiate sports encouraged fealty—and taxpayer support—among wide swaths of citizens who took great pleasure in competitive athletic rivalries even when they cared little about esoteric learning.[29] The cumulative result was that Americans not only supported their universities with public monies and private gifts, but also very often loved “their” schools—and still do—claiming affiliation with specific institutions as marks of honor and adorning their homes, cars, and bodies with symbols of their affection.[30]

Erosion of the Twentieth-Century Contract

The maintenance of the academic social contract relied on a great deal of reciprocal trust that would ultimately prove fragile in the face of enduring racism and tectonic changes in economic and global geopolitical affairs.

The mid-century rights movements and the War on Poverty expanded access to low-cost higher education and other publicly subsidized social services. But this expansion also led to political backlash. Angered by the success of Democrats in the 1960s and sensing an opportunity, Republican party leadership leveraged the alienation of many white voters and recruited them to capture the presidency for Richard Nixon in 1968 and again for Ronald Reagan in 1980.[31] White resentment at redistributive social policies also fueled what came to be called “the permanent tax revolt,” beginning with the passage of California’s Proposition 13 in 1978 and ultimately spreading nationwide. Americans’ growing allergy to taxes made it increasingly difficult for state legislatures to raise money to support access to public higher education, leading to a secular decline in public higher education funding nationwide virtually ever since.[32]

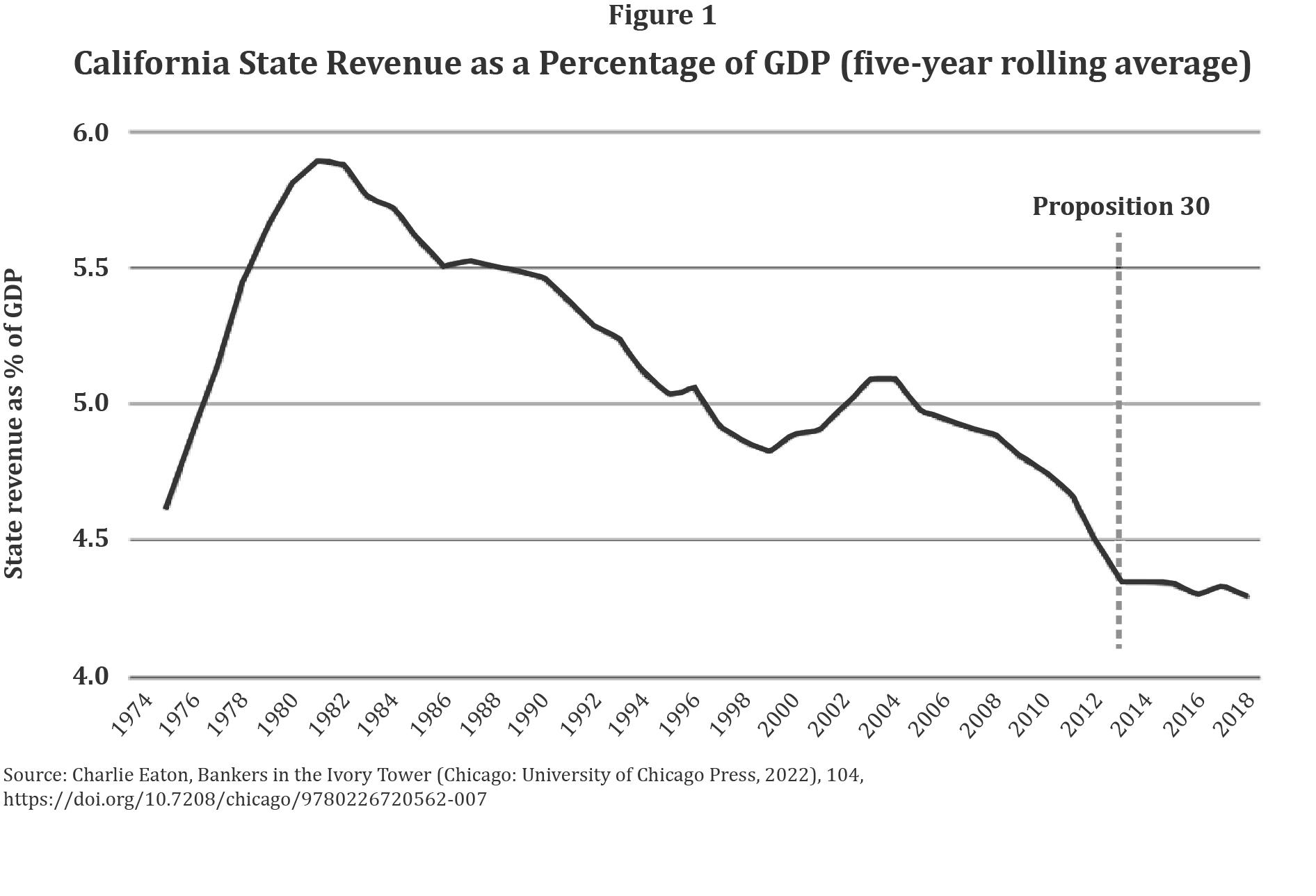

University of California, Merced sociologist Charlie Eaton uses the case of California to illustrate how the mid-century tax revolts created a secular decline in state capacity to raise revenue. See Figure 1. After decades of steady growth, tax revenues as a percent of state GDP declined steadily for decades, abating only between 1998 and 2003, then slowing somewhat after the passage of Proposition 30, an income tax on individuals making more than $250,000 per year, approved by voters in 2012. Nonetheless, over forty years of declining revenue ultimately meant fewer dollars were available to pay for higher education. California lawmakers instead prioritized spending on social welfare and prisons. As a result, between 2001 and 2011 per-student funding for University of California schools was cut by half.[33]

The decline of subsidies for public colleges and universities was enabled by the discretionary character of this funding. Unlike K-12 education, in which states are obliged to provide funding for all citizens as a matter of right, the provision of higher education in most states is fungible. Despite enthusiastic “college for all” and “free college” movements, higher education has never been given the status of citizen right in this country. This means that academic leaders need to constantly lobby for their share of state budgets. As the Baby Boom generation moved into mid-life and cohort sizes of high school students declined, so did broad-based support for public higher education. Additionally, the steady rise in state outlays for healthcare and steadily growing prison populations created ever more intense competition for limited tax revenues.[34] While the resulting secular decline in state subsidy of public higher education did not directly affect the fortunes of the admissions-selective private schools that are our focus here, it would gradually expand the differences in wealth and fiscal autonomy between a handful of relatively privileged private institutions and the sector as a whole.

The close of the twentieth-century Cold War further eroded the imperative for public subsidy for public and private schools alike. An imperative to demonstrate the civic virtue of American-style democratic capitalism to the world ended with the demise of its alternatives on the global stage. In a change of political epoch that some would call “the end of history,”[35] the rationale for multifarious arts and academic funding that had contributed so much to a national cultural efflorescence disappeared.[36] Federal government funding for these sectors has been more contingent ever since.[37]

This is where the academic social contract that expanded so voluminously through the 1960s began to exhibit its first major signs of strain. The tax revolts, coupled with the ideological shifts precipitated by the end of the Cold War, subtly changed the value proposition of higher education for large swaths of the American people. White working-class citizens, specifically, whose counterparts in the 1940s and 1950s became enamored of higher education when it was offered as a reward to their sons for military service, began to look elsewhere for social validation and political inspiration.

This same period saw the rise of institutional rankings as status arbiters among colleges and universities. Until this time, inter-institutional status was defined diffusely, often based on historical provenance and athletic conference affiliation (consider the Ivy League), or by regional primacy (consider the University of Chicago and Northwestern in the upper Midwest; Duke in the South; USC and Stanford in the West). In the space of two decades between 1983 and 2000, third-party ranking schemes transformed how institutions calibrated their prestige in relation to one another and changed how they made fundamental strategy and budgeting decisions. Because prospective students, donors, and alumni increasingly kept an eye on rankings, university leaders did as well. Programs and budget lines that did not directly contribute to ranking criteria—including many public service activities that did not “count”—grew increasingly hard to justify and sustain.[38]

Meanwhile, a few private institutions began to experience extraordinary financial prosperity. Encouraged by their alumni in the financial industry and a new cadre of experts in elite philanthropy, university trustees began realizing that their endowments could be leveraged for substantial growth.[39] Due to their relative autonomy from state legislatures and the incremental accretion of their endowments over many generations of patronage, private schools were placed in a significantly different relation to financial markets compared to their public sector peers. Experimenting with many of the same novel financial strategies that transformed Wall Street in the 1980s and 1990s, endowment managers created substantial new wealth in the private postsecondary sector—especially at those handful of lucky institutions that entered the post-Cold War era with already sizable endowments.

In the 1980s, the long bull stock market and the introduction of revolutionary portfolio investing techniques led many endowments to soar. So-called “active management strategies,” whose agents sought to out-perform market trends, began to replace “passive” strategies at elite institutions that could afford higher fees. Portfolio diversification—pioneered by Yale’s Chief Investment Officer, David Swenson, beginning in 1985—also rose to prominence in the mid-1980s, allowing elite universities to invest across different asset classes, in turn hedging their risk during down markets.[40]

The new investment approaches and favorable market conditions allowed a handful of relatively rich universities to fund more research, hire more professors, and increase annual operating budgets. The wealthiest schools were able to expand their budgets and grow their endowments simultaneously, creating a compounding effect that further distanced them from all others. A few endowments ascended into unprecedented new heights. From 1980 to 2016, the wealthiest 1 percent of university endowments—including Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Stanford, and MIT—saw their assets grow tenfold, with averages jumping from $2 billion to $20 billion.[41]

While the financial fates of public and private institutions diverged from the 1990s forward, the sticker price of completing a four-year degree rose virtually everywhere. See Figure 2. Over the last 20 years, there has been a 124 percent increase in the average cost of tuition at four-year private institutions.[42] This amounts to an average annual increase of 6.2 percent. Similarly, tuition at public four-year institutions rose 179 percent over the last 20 years, averaging a 9 percent annual increase.[43]

While social scientists continue to debate and specify just how the cost of four-year degrees continues to spiral, a few causal factors stand out as especially strong. First, demand for degrees from elite schools with known “brands” and selective admissions has become ever more desirable as families realize how useful these credentials are as insurance policies for the socioeconomic futures of their own children.[44] With rising household income and wealth inequalities from the 1980s forward, middle- and upper-middle-class families exhibited a “fear of falling,” as Barbara Ehrenreich famously put it.[45] They increasingly organized their own finances and their children’s lives to prepare them for entry into “name” colleges associated with lucrative first jobs and prosperous marriages. This demand mitigated concerns about rising sticker prices.[46]

Despite growing tuition costs, students and their families were often insulated from recognizing the full cost of their own college educations due to increasingly generous loan programs that forestalled payment into the future. The loans were backed by the legitimacy of the federal government, and the promises of social scientists that college indebtedness was “good” debt that paid off with higher wages in the long run.[47] This is the context in which public schools, increasingly searching for non-government sources of revenue, and private schools eager to move up various hierarchies of institutional prestige, were able to increase tuition and fees faster than the rate of inflation year after year while still filling their classes.

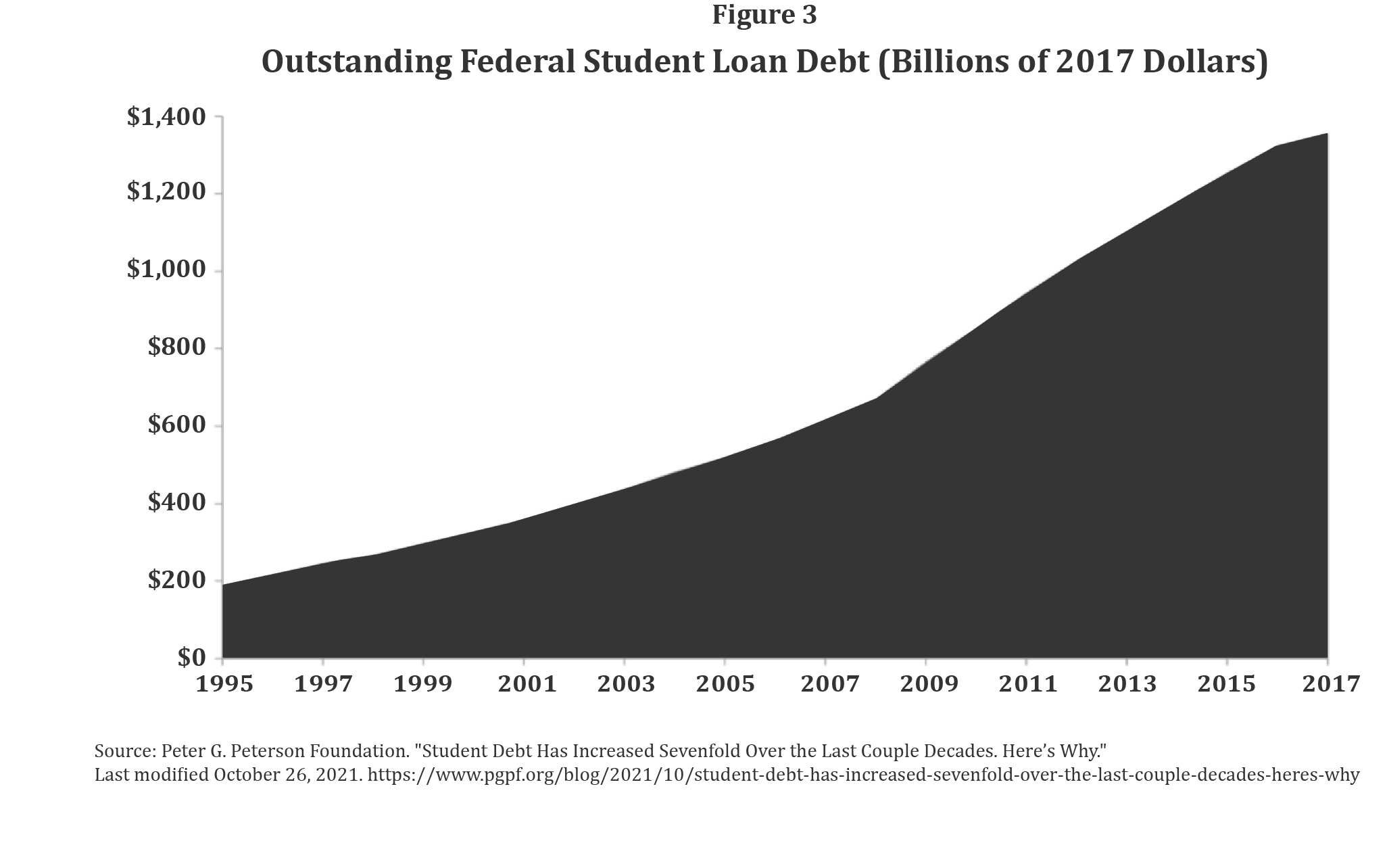

The growing burden of student loans has played a crucial role in shaping the higher education landscape. Figure 3 depicts the alarming trajectory of that growth in recent years. Federally backed student loan programs expanded significantly at the turn of the century. In 1995, the balance of outstanding federal student loan debt was $187 billion; it currently stands at $1.6 trillion.[48]

Several factors contributed to this exponential growth. The perceived need to receive a college degree to secure financial prosperity created great demand. Between 1995 and 2017, the number of borrowers increased from 4.1 million to 8.6 million.[49] Simultaneously, rising tuition costs led to larger amounts borrowed, and lower repayment rates. Among graduate students, the average amount borrowed in federal loans grew by 47 percent between 1995 and 2017, from $17,400 to $25,700. For undergraduates, the average loan size grew by 10 percent during the same period, from approximately $6,500 to $7,200.[50] Today, the average federal student loan debt balance is nearly $40,000.[51]

The steady rise in student loan debt undoubtedly contributed to souring public sentiment of higher education. Just what, exactly, were people getting in exchange for their loans—especially the millions of students who entered college in good faith but were never able to complete their degrees? And why were college costs continuing to rise nationwide, even while degree-completion rates notched up only incrementally, and there seemed to be no clear relationship between cost, quality, and time to degree?

In 2016, the growing populist movement and the presidential campaign of Donald Trump capitalized on these growing socio-cultural and class divides which were significantly influenced by disparities in college attainment. This movement harnessed the frustration of predominantly white, working-class Americans who felt alienated by the socioeconomic shifts and wealth disparities that favored people in possession of four-year college degrees.[52] A piece of legislation passed early in President Trump’s administration was a telling shot across the bow. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017-2018 levied a 1.4% excise tax on institutions with enrollments of more than 500 students that possessed endowments exceeding $500,000 per student in value. For the first time in history, the nation’s wealthiest and arguably most esteemed universities were penalized for their erstwhile success. Efforts to build on this precedent continue to garner momentum.[53]

Notably, one well-resourced institution—Berea College in Kentucky—was exempted from this tax through a provision that recognized its distinctive approach to deploying its more than $1 billion endowment.[54] Unlike its wealthy peers, Berea typically admits only students with significant financial need, charges no tuition, and actively uses its endowment to fund financial aid.[55] This legislative exception reveals how policymakers have drawn a line between an institution that is clearly using its resources to serve society and those they view as accumulating wealth without demonstrating a comparable societal impact.

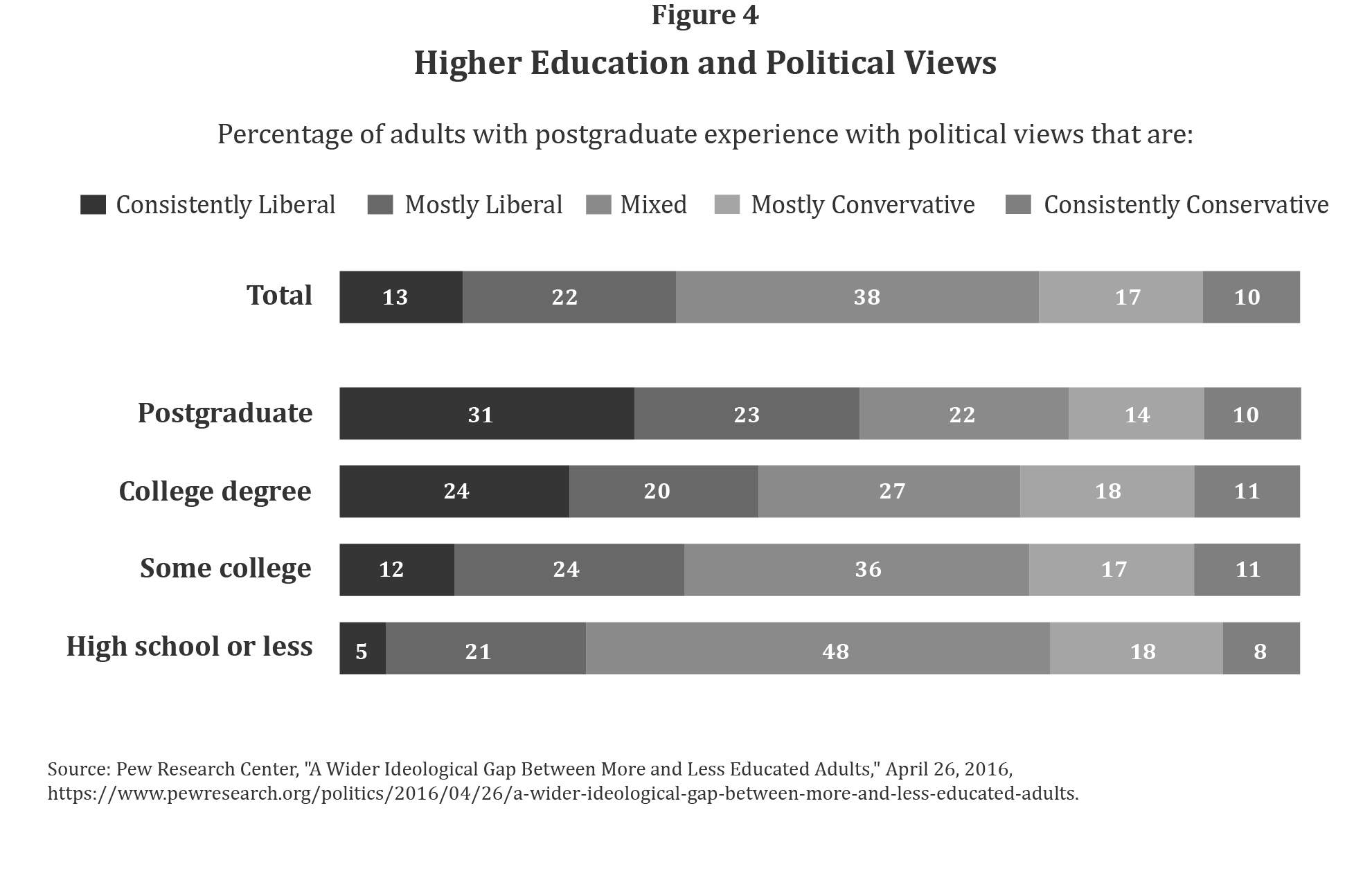

The years since have witnessed a proliferation of criticism of higher education generally, and elite universities specifically, to a level not seen since the 1960s. Populist rhetoric about “coastal elites” and the institutions they patronize resonates with voters who feel neglected by the political establishment and alienated from academia. Trump’s latest presidential campaign frames elite universities and intellectuals as out of touch with the everyday struggles of average Americans. The message landed. A Pew Research Center report published seven months before the November 2016 presidential election documented the growing ideological divide between more and less educated U.S. adults, with significant changes observed over the past two decades.[56] See Figure 4. Among those with postgraduate degrees, 54 percent held consistently liberal views in 2015, a sharp increase from 31 percent in 1994. This contrasted with those holding a high school diploma or less, where only 17 percent reported consistently liberal views in 2015, up from 12 percent in 1994. The widening gap in political values between college educated and non-college educated people underscores the role of education in shaping political ideologies. This divide contributes to the broader trend of political polarization, with educational attainment increasingly becoming a key factor in determining political alignment and views on key issues such as higher education.

The omnibus movement included prominent legal challenges, including the Students for Fair Admissions lawsuits against Harvard University and the University of North Carolina, which rendered race preferences in selective admissions illegal.[57] 2024 brought another spectacular challenge in the form of serial hearings convened by the U.S. House of Representatives’ Committee on Education and Workforce and featuring the presidents of some of the country’s most esteemed universities. Officially, the hearings were to investigate how the institutions were handling antisemitism in the wake of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict. Implicitly, they were mass-public excoriations of the elite academic establishment.

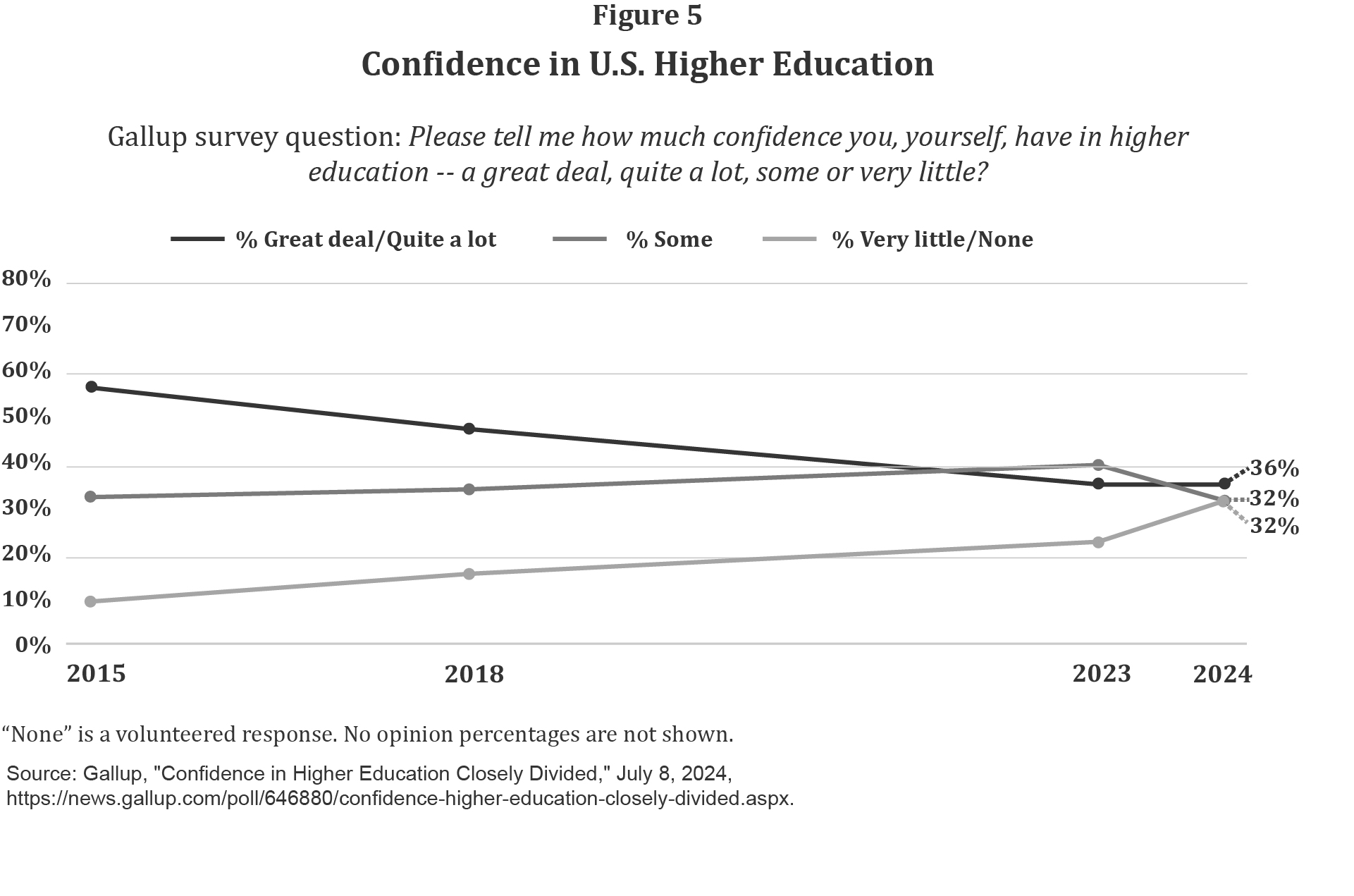

A 2024 Gallup poll reveals a significant decline in Americans’ confidence in higher education. See Figure 5. Approximately equal proportions of respondents profess a great deal or quite a lot of confidence, some confidence, and very little or no confidence—a substantial change since just 2015, when nearly 60 percent of respondents viewed higher education favorably.

Political affiliation is an important factor. 56 percent of Democrats and only 20 percent of Republicans currently hold high confidence in higher education institutions. Perceptions of the direction of higher education are also predominantly negative, with 68 percent of respondents believing it is heading in the wrong direction. Even among those with high confidence in the postsecondary enterprise, 30 percent share this pessimistic view.[58]

This decline in public confidence reflects an erosion that extends beyond teaching and access to research, traditionally the cornerstones of universities’ civic contribution. While America’s leading universities have historically spearheaded breakthrough research serving national interests and continue to do so in many areas, private industry increasingly dominates cutting-edge innovation. The rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines through Operation Warp Speed demonstrates this complex dynamic.[59] Universities contributed essential foundational research on mRNA technology, but pharmaceutical companies working in close partnership with the federal government—not academic institutions—ultimately led the rapid vaccine development and deployment.[60] Likewise, the AI revolution is being driven primarily by corporate labs, with companies like OpenAI, Google, Microsoft, and Anthropic leading advances and attracting top academic talent with superior computing resources and unprecedented compensation.[61]

While universities remain vital research centers and continue to collaborate with industry and government on key projects, their diminished role in addressing society’s most pressing challenges represents yet another dimension of the growing distance between higher education and the public it serves.

Major changes in the national economy and the global geopolitical order, compounded by shifts in how academic leaders navigate their own institutional fortunes and think about their public-service responsibilities, have created a growing rift between wealthy private institutions and everyday Americans that has strained the academic social contract – perhaps to a breaking point. Over the long arc of U.S. history, this is new. Prior epochs witnessed a steady expansion of the bargain struck between universities and the American people. Until relatively recently, the academic social contract was steadily expanded to include ever more civic functions for universities underwritten by public subsidy. Over the last forty years, however, Americans have grown incrementally more skeptical that the bargain they enter by subsidizing higher education—especially the wealthy private schools which now hold unprecedented wealth in the hands of a few —is a fair deal.

University leaders, trustees, alumni, and faculty must confront these circumstances even if they are not wholly responsible for them. We need to renegotiate the terms of the academic social contract to render it suitable for our times.

Renewing the Academic Social Contract

The nation’s leading private colleges and universities, long and still the envy of the world, now face an unprecedented loss of faith among the citizens and taxpayers whose support is crucial for institutions’ (and we believe the nation’s) continued flourishing.

It certainly is not news that many aspects of U.S. higher education need improvement.[62] Various data together paint a picture of low rates of intergenerational social mobility, tepid rates of timely completion, and continually rising costs. Yet great challenges also present opportunities for transformative change, and history offers ample precedent for U.S. universities substantially remaking themselves. A great asset of American higher education is just how nimble and proactive its most entrepreneurial leaders have proven to be. In our view the task is to mobilize the nation’s colleges and universities to commit to tackling the largest challenges of our time: growing socioeconomic inequality and the political division it engenders.

Possession or non-possession of a four-year college degree has become a caste-like distinction in American life: separating those who can reasonably expect economic stability and physical health over longer lives from those who cannot. The higher education enterprise is directly implicated in this problem.[63] We believe the academy’s most ambitious leaders are ideally positioned to help redress it, and we see great promise in assembling a national movement within the U.S. academy to do just that.

Any such movement would implicate many stakeholders. As this discussion has emphasized, colleges and universities have long had symbiotic relationships with government. Federal, state, and local political bodies all engage with universities and can influence their decision-making. The internal governance of universities also entails multiple parties. Named administrators exercise authority over most aspects of university functioning, but that oversight is shared with trustees, who bear a fiduciary relationship to the institution and exercise final authority over decisions that might impact the financial position of the institution. Governance is also shared with the faculty, and while the particulars of that sharing differ across schools, faculty everywhere have a say in matters of instruction and research. The multiplicity of parties who have a hand in university decision-making—and, thus, in crafting the academic social contract—is both a source of the resilience of the university model and potentially an impediment to substantial change.

Yet substantial change is what the current moment requires, and moving forward will not be easy. Unlike in previous historical epochs, university leaders cannot presume that federal and state governments will be eager partners in the great task of remediating today’s domestic challenges of economic inequality and political division. And they will need to work against deeply entrenched habits of thought and action within their own institutions which prioritize status competition and revenue growth over public service.

Nonetheless, a non-trivial number of private institutions also enjoy great wealth of endowment, academic talent, and autonomy. These resources position them well to champion a movement that could forge an unlikely alliance across the higher education landscape. While this alliance may include various entities—Christian colleges, community colleges, Historically Black Colleges and Universities, and public universities—we believe transforming higher education requires collective action from not only the wealthiest institutions but also a diverse range of schools that fully represent the challenges and potential of American higher education. This movement must also involve young people, for example, those aged 10-24, who will be most affected by changes in postsecondary education and can offer unique perspectives as both the nation’s future workforce and the students we aim to serve.

To effectively address the challenges in higher education and leverage the opportunities they present, we must confront and reconcile several key tensions that exist within the system. The tensions reflect a complex interplay between institutional priorities and societal needs, highlighting areas where change is both necessary and demanding. In the sections that follow, we explore the tensions, providing a framework for rewriting the academic social contract for our time. While we offer some examples that highlight innovative ideas, we hardly claim to have all the answers. Our task is to spur discussion and work with our colleagues nationwide to identify promising avenues of action.

National Interest and Institutional Autonomy

A paradox lies at the heart of the academic social contract: the bargain must serve the interests of the nation while maintaining the intellectual and institutional autonomy that defines universities as distinctive organizations.[64] The resulting tension raises a critical question for higher education leaders and policymakers: How to strike a balance that ensures universities’ meaningful address of national problems while preserving the institutional independence essential to their mission?

Addressing this challenge requires articulating a vision of institutional autonomy that actively embraces civic responsibility. Institutional leaders—presidents, provosts, deans, trustees—will need to recognize a deep paradox of private higher education in this country: that the enterprise is simultaneously “private” and “civic.” Over decades—centuries—of iterative negotiation, private colleges and universities have carved a distinctive role for themselves in the organizational fabric of U.S. society. They are private institutions that receive substantial public subsidy on the promise that they serve the public interest. That promise obliges reciprocity and humility on the part of its academic beneficiaries. It also requires pushing back against a now ubiquitous presumption that private universities are businesses purveying commodities and properly serving their highest bidders.[65] While we recognize and indeed want to honor the business-like character of many university endeavors, we believe that business-like ways of thinking about value and obligation by themselves undermine the civic relationship between universities and citizens that has done so much to enable the American national project. If universities are businesses, they should be treated and taxed like businesses. It is because they are not (just) businesses but (also) civic servants that they deserve special treatment from government. Universities need to live up to the service mission inherent in their distinctive civic identity.

Embracing civic responsibility and serving the public interest can take on many forms. Many universities already have robust public service programs that offer students opportunities to engage in service learning by partnering and placing students with local nonprofits and government agencies. Few, however, have implemented a public service requirement as part of the undergraduate or graduate experience. Although such a requirement carries certain risks, it would elevate public service from a peripheral role to the core of university operations, realigning institutional priorities with the university’s mission. There are several ways to envision a public service requirement. For example, Tulane University requires all undergraduates to complete two semesters of service learning through approved programs, including service learning courses, academic service learning internships, and faculty-sponsored public service research projects.[66]

Universities can also serve the public interest through the careers their students pursue after graduation. Although the decision to choose a career path is often personal and complex, research suggests that graduates with student loan debt are less likely to choose public interest jobs, while those with less debt are more inclined to work in sectors such as education.[67] Schools might incentivize more students to enter public service professions by reducing student debt, which can be achieved in various ways. For example, while the federal Public Service Loan Forgiveness program requires 10 years of public interest work, might more students decide to become K-12 teachers in low-income schools if their student loans were fully forgiven (covered by the university) after five years of qualifying service? By reducing financial barriers, universities can encourage more graduates to pursue careers in public service.

A public service requirement at selective private schools may also help limit the subtle but powerful ways in which institutions encourage undergraduates to pursue a handful of financially lucrative careers. In a process sociologists have dubbed career funneling, elite schools systematically cater to the recruitment ambitions of elite firms in tech, finance, and consulting fields by brokering access to undergraduates as early as the first or second college years. Students who are increasingly anxious about making good on their families’ investments in expensive educations reciprocate on recruiters’ interest. A cumulative result is the diminished prestige of modestly compensated careers in civic and public service.[68] A nationwide movement of college students is underway to combat this problem.[69] Selective institutions might do well to join them.

Competition and Collaboration

American higher education is pulled between competition and collaboration. The system traditionally rewards institutions, faculty, and students who outperform their peers with greater influence, resources, and prestige. This pursuit of excellence often drives institutions to compete fiercely for students, researchers, and funding, spurring remarkable innovation and elevating our top universities to world-leading status.[70] However this competitive model can also foster a zero-sum mentality, implying the inevitability of winners and losers, which ultimately undermines the collective strength and potential of the entire postsecondary system. How can we preserve the competitive quality that has made our top universities world leaders, while simultaneously fostering collaboration that sustains the health of the entire ecology, particularly for the thousands of institutions serving the vast majority of students?[71]

Moving beyond zero-sum conceptions of institutional success might entail inter-institutional partnerships to counter the hard facts of resource stratification that now define the sector. One example is the National Science Foundation’s pilot program in the CHIPS (Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors) and Science Act that encourages collaborations between top-tier research universities and “emerging research institutions” receiving less than $50 million in annual federal research expenditures.[72] Further development of patronage models for multi-institutional collaborations that promote distributed growth and excellence in research and training is well worth pursuing.

Additionally, partnerships between institutions which historically serve different demographic groups could also be prioritized. Telling instances of the promise of such endeavors include the 60-year partnership between Brown University and Tougaloo College[73] and a newly formed scholarship program at Yale, which benefits New Haven public school students who enroll in historically Black colleges and universities.[74] Given the sprawling scale of our higher education system, it strikes us as telling that so few such partnerships have been spawned to date. We worry that this represents an ossification of academic status distinctions which have come to inhibit, rather than enable, the promise of social mobility that has been part of the American academic social contract for generations.

Meritocracy and Democracy

The U.S. higher education system has long been shaped by ideals of meritocracy, rewarding and elevating those few who demonstrate exceptional accomplishments according to a few narrow yardsticks of ability and talent.[75] This meritocratic impulse to attract the “best” students and ultimately generate the most groundbreaking ideas has an inevitable consequence: exclusion. When elite institutions gather the “best,” they inevitably exclude many accomplished others from their educational opportunities and vast resources. Yet democratizing access to higher education is fundamentally in America’s national interest, essential for building a skilled workforce, an informed citizenry, and an innovative economy. The tension between excellence and access highlights another key dilemma: How to design a system that accommodates the selectivity elite institutions view as integral to their identity, while also democratizing access and promoting social mobility?

For admissions-selective schools to serve as true engines of social mobility, they may need to create pathways specifically designed to serve students from a wider range of life stages and circumstances. Serial critiques of the meritocracy trap have taught us as much.[76] Doing so might entail expanding enrollment tenfold, for instance, by establishing new campuses[77] and focusing outreach on historically underrepresented students, including those from rural areas and veterans. Schools could also aim to increase the proportion of Federal Pell Grant recipients in incoming classes to 50 percent, a change that would have a profound impact on students from low-income backgrounds.[78]

Admissions-selective institutions may additionally form partnerships with other institutions that are more porous to students from a wide range of life circumstances. We note for example Southern New Hampshire University’s robust set of credit-transfer agreements with community colleges across the U.S.[79] The National Education Equity Lab has also developed an innovative approach to cross-sector partnerships, enabling students in under-resourced high schools to earn college credit by participating in dual enrollment programs with institutions like Stanford, Howard, and soon MIT.[80] Additionally, pre-collegiate academies that leverage technology and hybrid learning could be implemented to scale access to courses and instruction from admissions-selective institutions for thousands of low-income students. These enriching educational opportunities have significant potential to change their career trajectories, even if they never attend the host university.

More ambitiously: we see no insurmountable barrier to partnerships wherein admissions-selective private universities receive entire cohorts of transfer students who first obtain their two-year associate diplomas from public community colleges. The University of California and California State University campuses have been doing this for years, with positive results on measures of intergenerational social mobility[81] and at no evident loss to excellence. This accomplishment has not been without its detractors, yet California law requires what has become a hallmark of the state’s higher education ecosystem. Private institutions might emulate this model, securing patronage from their alumni and friends for novel hybrid programs. Policymakers might write expectations for such partnerships into requirements for receipt of Title IV or research funding.

More radically, universities might cede some of their grip over the nation’s employment credentialing process in the interest of lowering barriers separating talented people from well-compensated and career-laddered jobs. The research and advocacy non-profit Opportunity@Work has amply documented how more than 70 million working Americans are categorically disadvantaged in labor markets that explicitly and legally discriminate against jobseekers who do not have four-year college degrees.[82] We can only begin to imagine the role elite institutions might play in helping to create a new national system of recognizing and certifying talent wherever it may have been nurtured.

Four-Year Degrees and Lifelong Learning

Wealthy, private, admissions-selective schools remain organized around a four-year residential college experience for emerging adults. This model has encouraged personal growth, intellectual development, and enduring social connections for generations of students. However, it also creates a situation where the most coveted educational opportunities are largely reserved for 18-22-year-olds, who constitute a minority of college students.[83] Our system’s focus on youth comes at a time when rapidly evolving technology and changing workforce demands underscore the importance of continuous learning throughout a career. The tension between the established four-year model and the growing need for lifelong learning suggests yet another pressing question: How might the nation evolve higher education to maintain the benefits of immersive learning experiences while better serving the diverse educational needs of individuals across their lifespans?

Tackling this issue may require reimagining the timing and structure of higher education. One approach could involve distributing college years over a lifetime, as envisioned by our colleagues at Stanford’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design in their Open Loop University—a student-led initiative—that replaces four consecutive college years in young adulthood with multiple residencies distributed throughout one’s life.[84] Developing more flexible online and hybrid learning options could also provide greater accessibility and adaptability for learners at various life stages. An innovative example of this integration is Minerva University, founded in 2012 in San Francisco. Years before the coronavirus pandemic, Minerva combined classic seminar-style classes with a technology platform and globally mobile classroom, allowing students to learn in flexible ways and diverse settings—a model it has further adapted to partner with more universities.[85]

We note also the creation of whole new colleges by Butler University (Indianapolis) and Loyola University (Chicago), specifically targeting populations that historically have not been well-served by legacy four-year degree programs. Butler’s Founder’s College and Loyola’s Arrupe College offer two-year Associates diplomas and commit to enabling enrollees to graduate without debt. Such models make it easier to imagine parallel innovations that might (for example) enable holders of Associate’s diplomas to obtain high-quality, affordable four-year degrees. Programs such as these would materially demonstrate legacy institutions’ commitment to accessibility, and social mobility.

Innovation and Preservation

Universities are unique institutions because they must look both backwards and forwards—delving into the past, teaching history, and extracting its lessons, while simultaneously developing the thinkers and ideas of tomorrow. This dual role creates an innate tension between innovation and preservation in American higher education. We expect—and indeed need—our universities to be at the forefront of discovery and progress, pushing boundaries in research and adapting to rapidly changing societal needs. At the same time, they serve as caretakers of our collective knowledge, upholding academic traditions and maintaining continuity with the past. How can we promote a culture of innovation that propels our institutions—and nation—forward while preserving the valuable academic approaches and knowledge that form the bedrock of higher education?

Answering this question may call for creating partnerships between universities, government, and industry in substantially new ways. MIT’s transformation of Cambridge’s Kendall Square into a biotechnology hub, which gave rise to pharmaceutical firm Moderna and its COVID-19 vaccine, demonstrates the potential of exploring novel cross-sector collaborations.[86] How might similar audacity be deployed to develop cross-sector efforts to combat domestic economic inequality and political division? We know of at least a few nascent efforts in this direction. The Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins University, for example, aims to strengthen democracy through civic discourse and inclusive dialogue. Agora is an entirely new academic unit, specifically purposed with bridging academic and public conversations on the future of democracy in the U.S. and worldwide.[87] At Stanford’s Hoover Institution, a new Center for Revitalizing American Institutions seeks to address the crisis of trust evident across the entire fabric of national organizational life, and nurture fresh ways of addressing this problem.[88] More broadly, we know that universities have perennially grown and changed in form to meet evolving real-world problems.[89] There is no reason why that process cannot continue in the address of the grand challenges of our own time.

Institutional structures that can nimbly respond to societal changes may also be needed, with wisdom gleaned from unexpected sources. Consider the hard but important lesson of the rise of the for-profit postsecondary sector. In the first decades of the 21st century, for-profit colleges showed remarkable agility, quickly opening new schools, hiring faculty and adding programs in fields with great pent-up demand, such as healthcare.[90] Yet their early “success” at business operations came at substantial human cost: millions of ambitious college-goers indebted to organizations which had little interest in students’ degree completion or economic well-being.[91] In our view, this difficult chapter in higher education history suggests the civic risks that attend inflexibility and inaction by legacy providers. Forward efforts to develop new forms of educational opportunity must not repeat past errors—even while preserving the proactive and entrepreneurial energy that is one of American higher education’s distinctive strengths.

We see promise, for example, in innovative models and efforts to make college degrees more accessible to people at different life stages. Western Governors University challenged the traditional time-in-seat classroom model by designing a competency-based distance education program and contributing to broader discussions about educational assessment and delivery.[92] This approach has gained significant attention, with former U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan advocating for competency-based education programs to “be the norm,”[93] clear evidence that large research universities can be extraordinarily flexible and creative while maintaining their commitment to research and academic rigor.[94]

* * *

The tensions are not new, but they have been exacerbated by the increasing stratification of the national higher education ecology and the widening economic and political divides it both reflects and enhances. The gap between elite private universities and other institutions has widened, creating an upward spiral of resources, selectivity, and status that threatens to undermine the entirety of the academic social contract.

We call on the leaders of the institutions on which history has bestowed exceptional fortune to spearhead a renegotiation of the contract that has done so much to enable and fulfil the American story. The renegotiation should begin with a collective reckoning—a thorough and honest examination of our institutions’ histories, missions, and current practices—with the aim of freshly defining what it means for especially privileged schools to be true servants of a democratic society. We hope that our modest effort here does something to motivate and inform that endeavor.

[1] Anthony P. Carnevale, Peter Schmidt, and Jeff Strohl, The Merit Myth (New York: The New Press, 2020).

[2] Michael Sandel, The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2020); Daniel Markovits, The Meritocracy Trap: How America’s Foundational Myth Feeds Inequality, Dismantles the Middle Class, and Devours the Elite (London: Penguin Press, 2020).

[3] Neil Gross, Why are Professors Liberal and Why do Conservatives Care (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013); Amy J. Binder and Jeffrey L. Kidder, Channels of Student Activism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022).

[4] Joel Best and Eric Best, The Student Loan Mess (Oakland: University of California Press, 2014); Caitlin Zaloom, Indebted (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019).

[5] National Center for Education Statistics, “Fast Facts: Undergraduate Graduate Rates,” U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, accessed August 1, 2024.

[6] Michael Hout, “Social and Economic Returns to College Education in the United States,” Annual Review of Sociology 38, (August 2012): 379-400; Ilana M. Horowitz and Mitchell L. Stevens, “Reimagining Education for a New Map of Life,” Stanford Center on Longevity, last modified November 16, 2021.

[7] Joshua N. Zingher, “TRENDS: Diploma divide: Educational attainment and the realignment of the American electorate,” Political Research Quarterly 75, no. 2 (April 2022): 263-277.

[8] Nathan Born and Adam Looney, “How Much Do Tax-Exempt Organizations Benefit from Tax Exemption?” Tax Policy Center Research Report, July 27, 2022; Tax Policy Center, “How large are individual income tax incentives for charitable giving?” The Tax Policy Briefing Book; Nic Querolo, Amanda Albright, Janet Lorin, and Jeremy C.F. Lin, “Harvard’s $465 million in tax benefits draw new scrutiny,” Bloomberg, July 25, 2024.

[9] Joshua Kim, “Endowments, 1990-2055,” Inside Higher Ed, September 6, 2023.

[10] “Social Contract,” Merriam-Webster Dictionary, last updated July 8, 2024.

[11] Emily J. Levine, Allies and Rivals: German-American Exchange and the Rise of the Modern Research University (Chicago, 2021); Emily J. Levine and Mitchell L. Stevens, “Negotiating the Academic Social Contract,” Change 54, no. 1 (January 2022): 2-7.

[12] Emily J. Levine, “Research and Teaching: Lasting Union or House Divided?” Daedalus 153, no. 2 (Spring 2024): 21-35.

[13] Levine, Allies and Rivals, 3.

[14] Mitchell L. Stevens and Ben Gebre-Medhin, “Association, Service, Market: Higher Education in American Political Development,” Annual Review of Sociology 42 (July 2016): 121-142.

[15] Frederick Rudolph, The American College and University: A History (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1990), 48.

[16] Sharon Stein, Unsettling the University (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2022).

[17] Craig Steven Wilder. Ebony & Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2013).

[18] James D. Anderson, The Education of Blacks in the South: 1860-1935 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988); Joan Malczewski, Building a New Educational State: Foundations, Schools and the American South (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016); Deondra Rose, The Power of Black Excellence: HBCUs and the Fight for American Democracy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024).

[19] Laura T. Hamilton, Caleb E. Dawson, Elizabeth A. Armstrong, and Aya Waller-Bey. “Racialized Horizontal Stratification in US Higher Education: Politics, Process, and Consequences,” Annual Review of Sociology 50 (May 2024); Ruth Simmons, “Slavery and Justice at Brown: A Personal Reflection,” from Slavery and the University: Histories and Legacies, ed. Leslie M. Harris, James T. Campbell, Alfred L. Brophy. (University of Georgia Press, 2019).

[20] Christopher P. Loss, Between Citizens and the State: The Politics of American Higher Education in the 20th Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014).

[21] Bureau of the Census, “Census Questionnaire Content, 1990 CQC-13,” Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce, September 1994.

[22] Nicholas Lehmann, The Big Test: The Secret History of the American Meritocracy (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999), 59-60.

[23] Suzanne Mettler, Soldiers to Citizens: The G.I. Bill and the Making of the Greatest Generation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[24] Margaret O’Mara, Cities of Knowledge: Cold War Science and the Search for the Next Silicon Valley (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004); Daniel Lee Kleinman, Politics on the Endless Frontier (Durham: Duke University Press, 1995); Alexander T. Kindel and Mitchell L. Stevens, “What is educational entrepreneurship? Strategic action, temporality, and the expansion of US higher education,” Theory and Society 50 (April 2021): 577-605.

[25] Roger L. Geiger, American Higher Education since World War II: A History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019).

[26] Randall Collins, The Credential Society: An Historical Sociology of Education and Stratification (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019 [1979]).

[27] Bureau of the Census, “Census Questionnaire Content, 1990 CQC-13,” Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce, September 1994; National Center for Education Statistics, “Rates of high school completion and bachelor’s degree attainment among persons age 25 and over, by race/ethnicity and sex: Selected years, 1910 through 2015,” Institute of Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, last updated November 2015.

[28] Lauren A. Rivera, Pedigree: How Elite Students Get Elite Jobs (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

[29] Charles T. Clotfelter, Big-Time Sports in American Universities (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

[30] Paul Fussell, “Schools for Snobbery,” The New Republic, October 4, 1982.

[31] Matthew Lassiter, The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007).

[32] Isaac Martin, The Permanent Tax Revolt: How the Property Tax Transformed American Politics (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008); Monica Prasad, Starving the Beast: Ronald Reagan and the Tax Cut Revolution, (New York: Russel Sage Foundation, 2018); Charlie Eaton, Bankers in the Ivory Tower: The Troubling Rise of Financiers in US Higher Education (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022), 102-104.

[33] Charlie Eaton, Bankers in the Ivory Tower: The Troubling Rise of Financiers in US Higher Education (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022), 104.

[34] Patricia J. Gumport and Brian Pusser, “University Restructuring: The Role of Economic and Political Contexts.” In J. Smart (ed.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research. Volume VIV (Bronx, NY: Agathon), 1999.

[35] Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Free Press, 2006).

[36] Louis Menand, The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2021).

[37] Mitchell L. Stevens and Ekaterina Shibanova, “Varieties of state commitment to higher education since 1945: toward a comparative-historical social science of postsecondary expansion,” European Journal of Higher Education 11, no. 3 (June 2021): 219-238.

[38] Wendy Nelson Espeland and Michael Sauder, Engines of Anxiety: Academic Rankings, Reputation, and Accountability (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2016).

[39] Charlie Eaton, The Ivory Tower Tax Haven: The state, financialization, and the growth of wealth college endowments (Berkeley: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, 2017).

[40] David F. Swenson, Pioneering Portfolio Management: An Unconventional Approach to Institutional Investment (Los Angeles: The Free Press, 2009); “David Swenson’s Coda,” Yale News, October 22, 2021.

[41] Charlie Eaton, “Elite private universities got much wealthier while most schools fell behind. My research found out why,” The Washington Post, November 4, 2021.

[42] Melanie Hanson, “Average Cost of College by Year,” Education Data Initiative, last updated January 9, 2022.

[43] Melanie Hanson, “Average Cost of College by Year,” Education Data Initiative, last updated January 9, 2022.

[44] Mitchell L. Stevens, Creating a Class: College Admissions and the Education of Elites (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009).

[45] Barbara Ehrenreich, Fear of Falling: The Inner Life of the Middle Class (New York: Twelve, 1989).

[46] Caitlin Zaloom, Indebted: How Families Make College Work at Any Cost (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019).

[47] Joel Best and Eric Best, The Student Loan Mess: How Good Intentions Created a Trillion-Dollar Problem (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014); Tressie McMillan Cottom, Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profit Colleges in the New Economy (New York: The New Press, 2018).

[48] Melanie Hanson, “Student Loan Debt Statistics,” Education Data Initiative, last updated July 15, 2024. (According to the source, “The outstanding federal loan balance is $1.620 trillion and accounts for 91.2% of all student loan debt.”); David Burk and Jeffrey Perry, “The Volume and Repayment of Federal Student Loans: 1995 to 2017,” Congressional Budget Office, (November 2020).

[49] “Student Debt Has Increased Sevenfold Over the Last Couple Decades. Here’s Why,” Peter G. Peterson Foundation, October 26, 2021.

[50] David Burk and Jeffrey Perry, “The Volume and Repayment of Federal Student Loans: 1995 to 2017,” Congressional Budget Office, (November 2020).

[51] Melanie Hanson, “Student Loan Debt Statistics,” Education Data Initiative, last updated July 15, 2024. For information on debt by institutional type, see Lyss Welding, “Average Student Loan Debt: 2024 Statistics,” Best Colleges, last updated May 30, 2024.

[52] Mitchell L. Stevens, “Higher Education Politics after the Cold War,” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 50, no. 3-4 (October 2018): 13-17.

[53] See for example Marc Schneider and Jorge Klor de Alva, “A tax on university endowments can help reduce our labor shortage,” The Hill, June 5, 2024.

[54] Michelle Hackman, “Kentucky College Gets Tax Exemption in Budget Deal,” The Wall Street Journal, February 8, 2018.

[55] Gretchen Dykstra, Lessons from the Foothills: Berea College and Its Unique Role in America (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2024).

[56] Pew Research Center, “A Wider Ideological Gap Between More and Less Educated Adults,” Pew Research Center, April 26, 2016.

[57] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. Harvard, 600 U.S. 181 (2023).

[58] Jeffrey M. Jones, “U.S. Confidence in Higher Education Now Closely Divided,” Gallup, July 8, 2024; Gallup found that public confidence in many other American institutions has also declined significantly, including the military, judiciary, and national government. For example, in 2023, only 42 percent of Americans were confident in the judicial system, compared to 61 percent in 2017 and 59 percent in 2020. Benedict Vigers, “U.S.: Leader or Loser in the G7?” Gallup, April 17, 2024.

[59] Neil Irwin, “The Pandemic is Showing Us How Capitalism Is Amazing, and Inadequate,” The New York Times, November 14, 2020.

[60] William B. Bonvillian, “Operation warp speed: Harbinger of American industrial innovation policies,” Science and Public Policy, July 29, 2024.

[61] See Nur Ahmed et al., “The growing influence of industry in AI research,” Science 379, 884-886 (2023); Isabelle Bousquette, “Universities Don’t Want AI Research to Leave Them Behind,” The Wall Street Journal, July 12, 2024; Naomi Nix, Cat Zakrzewski, and Gerrit De Vynck, “Silicon Valley is pricing academics out of AI research,” The Washington Post, March 10, 2024; see also Jason Owen-Smith, Research Universities and the Public Good: Discovery for an Uncertain Future (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018).

[62] Paul Tough, “Americans Are Losing Faith in the Value of College. Whose Fault Is That?” The New York Times, September 5, 2023; Jackie Valley, “Education secretary: America’s higher education system is ‘broken’,” The Christian Science Monitor, September 13, 2023; Karen Fischer, “The Barriers to Mobility: Why Higher Ed’s Promise Remains Unfulfilled,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, December 30, 2019; Adrian Wooldridge, “America’s Educational Superpower Is Fading,” Bloomberg, April 17, 2023.

[63] Mitchell L. Stevens, “Higher Education Politics after the Cold War,” Change Magazine, 50 (2018):13-17.

[64] Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U.S. 250 (1957): “The essentiality of freedom in the community of American universities is almost self-evident. No one should underestimate the vital role in a democracy that is played by those who guide and train our youth. To impose any straitjacket upon the intellectual leaders in our colleges and universities would imperil the future of our nation. No field of education is so thoroughly comprehended by man that new discoveries cannot yet be made. Particularly is that true in the social sciences, where few, if any, principles are accepted as absolutes. Scholarship cannot flourish in an atmosphere of suspicion and distrust. Teachers and students must always remain free to inquire, to study and to evaluate, to gain new maturity and understanding; otherwise, our civilization will stagnate and die.” See also Charlie Eaton and Mitchell L. Stevens, “Universities as Peculiar Organizations,” Sociology Compass (January 2020).

[65] We recognize that this will be a tough hill to climb, since what Stanford sociologist Patricia Gumport has dubbed an ”industry logic” is so firmly entrenched in the thinking and administrative routines of US universities. Yet still vibrant is what Gumport calls a ”social institution” logic; Gumport’s industry / social institution distinction substantially parallels the private / civic distinction we make here. See Patricia J. Gumport, Academic Faultlines: The Rise of Industry Logic in Public Higher Education (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019).

[66] “Public Service Requirement,” Tulane University Center for Public Service, accessed September 22, 2024.

[67] Jesse Rothstein and Cecilia Elena Rouse, “Constrained after college: Student loans and early-career occupational choices,” Journal of Public Economics 95, no. 1-2 (February 2011): 149-163.

[68] Amy J. Binder, Daniel B. Davis, and Nick Bloom, “Career Funneling: How Elite Students Learn to Define and Desire “Prestigious” Jobs,” Sociology of Education, 89(1), (2016): 20-39.

[69] “Corporate Career Funneling,” Class Action Network, accessed October 30, 2024.

[70] For a synthetic essay see Jason Owen-Smith, Research Universities and the Public Good: Discovery for an Uncertain Future (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018).

[71] Danielle Allen, “Education and Equality,” The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, October 8, 2014.

[72] Congress.gov “H.R.4346 – 117th Congress (2021-2022): Chips and Science Act,” August 9, 2022; Jeremy Wolos and Steven C. Currall, “Not Just Chips,” Inside Higher Ed, September 12, 2022.

[73] “Brown-Tougaloo Partnership Program,” Brown-Tougaloo Partnership, accessed August 6, 2024; Stephen G. Pelletier, “Best Practices: Five Decades On, Brown-Tougaloo Partnership Still Thrives,” International Educator 26, no. 4 (July/August 2017): 42-43, ProQuest.

[74] Peter Salovey, “Announcing the Pennington Fellowship,” Yale University, December 12, 2022.

[75] Mitchell L. Stevens, Creating a Class: College Admissions and the Education of Elites (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009).

[76] Anthony Carnevale et al., The Merit Myth: How Our Colleges Favor the Rich and Divide America (New York: The New Press, 2020); Daniel Markovits, The Meritocracy Trap: How America’s Foundational Myth Feeds Inequality, Dismantles the Middle Class, and Devours the Elite (London: Penguin Press, 2019); Michael Sandel, The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2020); Mitchell L. Stevens, Creating a Class: College Admissions and the Education of Elites (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009).

[77] David L. Kirp, “Why Stanford Should Clone Itself,” The New York Times, April 6, 2021.

[78] Tom Corrigan, “The Top Colleges for Helping Students Move Up the Socioeconomic Ladder,” The Wall Street Journal, September 19, 2024.

[79] Lindsay McKenzie, “SNHU Moves into Pennsylvania,” Inside Higher Ed, January 9, 2020.

[80] Sunny Hong, “Leveraging Digital Innovation in College Admissions and Dual Enrollment,” Ithaka S&R, July 9, 2024.

[81] Raj Chetty et al., “Income Segregation and Intergenerational Mobility across Colleges in the United States,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 135, no. 3 (August 2020): 1567-1633. See also David Leonhardt, ”America’s Great Working Class Colleges,” New York Times, January 18, 2017.

[82] Jonathan Rabinovitz, “Playbook boosts community college efforts to help students get data analyst jobs,” Stanford Digital Education, June 19, 2024; Sagar Goel, “Competence over Credentials: The Rise of Skills-Based Hiring,” Boston Consulting Group, December 11, 2023; “Opportunity@Work: Addressing the opportunity gap and improving workforce equity outcomes,” McKinsey Institute for Black Economic Mobility, August 1, 2024.

[83] Mitchell L. Stevens, “College for Grown-ups,” The New York Times, December 11, 2014.

[84] “Open Loop University,” Stanford 2025, accessed August 7, 2024; “Uncharted Territory: A Guide to Reimagining Higher Education,” accessed August 7, 2024.

[85] Teri A. Cannon and Stephen Michael Kosslyn, “Minerva: The Intentional University,” Daedalus 153, no. 2 (May 2024): 275-285; Emily J. Levine and Matthew Rascoff, “Academic Innovation: The Obligation to Evolve,” Education Next, January 17, 2019.

[86] Robert Buderi, “Spotlight: Mapping the Moderna Network.” in The Where Futures Converge: Kendall Square and the Making of a Global Innovation Hub (Boston: MIT Press, 2022): 257-259.

[87] Sarah Larimer, “Johns Hopkins University Wants to Improve Civic Discourse. It Hopes a New Institute Can Help,” The Washington Post, June 27, 2017.